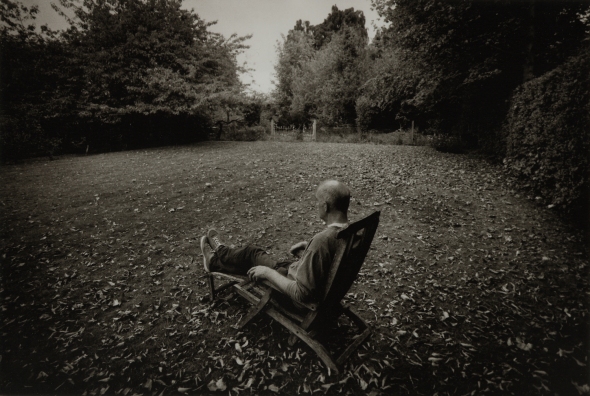

Another photo of Tim Andrews.

Posted: June 13, 2013 Filed under: Bohemian London, Gardens | Tags: Alex Boyd, Guardian Gallery, Harry Borden, Over The Hill, Parkinson's disease, The Culture SHow, Tim Andrews 1 Comment Tim Andrews, Surrey. © David Secombe 2010.

Tim Andrews, Surrey. © David Secombe 2010.

Tim Andrews, Over The Hill blog, 5 February 2012:

I love my body at the moment…..it’s not that I think it looks good (according to whatever criteria one uses to define a good looking body)……..it’s just that it is all I’ve got but this bloody disease is chipping away at it and I am hanging on to what physicality I still have…….and maybe that is why I do so much photography and filming in the nude………..well, partly why………..I do feel that clothes make statements which is fine but a body is just you, unadorned…….and it says so much more…….no I can’t tell you what more it says for I am a bear of little brain………..

In the luminous glass box of the Guardian Gallery, situated in the foyer of the newspaper’s offices in King’s Cross, I am surrounded by images of one man. This man is not a cultural figure or head of state; he is an ex-solicitor from Surrey who took early retirement following a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The occasion is the private view of Over The Hill: A Photographic Journey, subtitled ‘One man’s confrontation with his own mortality’, an exhibition (sponsored by Parkinson’s UK) featuring the work of 30 out of the 240-odd photographers who have photographed Tim Andrews since 2008. I was invited because the image above was selected – by The Guardian – as one of the exhibits.

Over The Hill is an unusual undertaking inasmuch as it is a form of extended self-portraiture by someone who is not an artist. Tim Andrews expresses himself by making himself available to photographers to photograph. One tries to think of precedents but the only one I can offer is that of a Renaissance prince, a Medici or similar, commissioning many portraits in order to contemplate his corporeal being. The difference between Tim Andrews and your average Medici is that Tim likes to be portrayed in the buff, and foregrounds this preference in discussions with the photographers. As indicated by the quote above, Tim equates nakedness with truthfulness, but this has always been contentious and is even more so when spoken by a subject keen to get his kit off for the camera.

At any rate, a wide range of photographers have been happy to photograph Tim and many have taken him up on his offer to disrobe; yet whilst their sympathy towards their subject is palpable, there are more than a few images wherein he appears as no more than a conceptual prop. The ex-solicitor is asked to represent weighty themes: the ‘identity of the body’, the nature of disability, and, yes, the confrontation with mortality. We see him as a wood nymph, as a saint, as Shiva, etc. Forensic psychological portraiture is at a premium (notable exceptions include Harry Borden and Alex Boyd) and there is also a note of competition, as big names and aspiring art photographers vie with each other to create the most eye-catching image of an increasingly desirable ‘scalp’.

What do we know about Tim Andrews? I can tell you that he is a very nice man who didn’t like being a solicitor – he really wanted to be an actor – who is one of the 127,000 people in the UK who suffer from Parkinson’s. I don’t know if Over The Hill tells us anything we didn’t already know about the condition – a difficult disease to depict in a still image – but it reveals something about Tim Andrews, and quite a lot about the nature of modern fame. His journey from frustrated provincial solicitor to art world pin-up has all the key ingredients of an Arts & Lifestyle feature: mid-life crisis, sudden illness, confessional memoir, nudity, and the glamour of association with celebrity (the distant connection between Tim Andrews and the famous subjects of the better-known photographers involved). I don’t doubt that Tim Andrews is anything less than utterly sincere, but it is hard to overlook the compulsive exhibitionism – masochism, even – of the project. And despite the accomplishment of much of the work in it, Over The Hill has the feeling of a scrapbook: Tim gives the pictures titles and adds a whimsical, inward-looking commentary that tends to smother them. No image is allowed to speak on its own terms. There is a lot going on here, but it needs someone other than the subject of the photos to unpack it.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the project is the oblique insight it affords us into the mystery of portraiture. Some of the most memorable faces on the planet are people famous only for their appearance in a great image: August Sander’s farmers, Paul Strand’s blind woman, Brassai’s drinker, Don McCullin’s shell-shocked marine, Diane Arbus’s boy in curlers, Eve Arnold’s Chinese lady, etc. We know nothing about the histories of these people but the images are indelible. On the other hand, we have the Great photographed by the Great; so here’s Francis Bacon by Bill Brandt, Truman Capote by Irving Penn, Ezra Pound by Richard Avedon, Camus by Cartier-Bresson – and, for that matter, Graham Greene by Dmitri Kasterine. Such portraits have myth-making capacity. By contrast, the subject of Over The Hill is both anonymous and celebrated; an ordinary man made extraordinary by the elaborate attention paid to him. It’s a cute story but, inevitably, the law of diminishing returns applies. The endless repetition of Tim’s body, with and without clothes, becomes a hall of mirrors: the more distorted the reflection, the less we apprehend the person in the frame. What the viewer sees is Tim looking at the photographers looking at him looking at them.

But none of these caveats really matter. It is clear that being seen is Tim’s overriding concern, the images themselves are of secondary importance. His story is redolent of an Edwardian bohemian fantasy, and if he’d lived in an earlier era he might have inspired a novel by Arnold Bennett or Somerset Maugham. He is The Man Who Lived Again; and he has used his failing body to proclaim his existence.

Over The Hill runs at the Guardian Gallery, King’s Place, London N1, until 21st June. A selection from the project is also on show at the Farley Farm House gallery, Sussex, during June and July.

Tom Sharpe.

Posted: June 6, 2013 Filed under: Literary London, Out Of Town | Tags: Porterhouse Blue, Riotous Assembly, The Throwback, Tom Sharpe, Wilt Comments Off on Tom Sharpe.Tom Sharpe, Cambridge, 1992. Photo © David Secombe

Farewell Tom Sharpe … the author of Wilt, Porterhouse Blue, The Throwback, Riotous Assembly, etc. has died at the age of 85.

As an adolescent, I loved Tom Sharpe’s books. In his 1970s pomp, his fierce, majestic and paralysingly funny satires were a cause for great joy, and even made one proud to be British. But it can be a tricky thing to meet your heroes; and driving to Cambridge in the company of a nervous Spanish journalist (on his first ever visit to the UK) to interview the great man, I was fighting off my own attack of nerves. The interview started a bit awkwardly, as my colleague tried a line of questioning about the power of literature, during which he asserted: ‘Madame Bovary changed my life’ – to which Tom replied, ‘Well, you can’t have met that many doctors’ wives’. Things settled down after that, and we ended up going to a local pub – driven there at high speed along wild Fen roads by the author himself – where I finally got my chance to tell him that I thought Chapter 4 of The Throwback was the funniest thing I had ever read.

We discussed contemporary comedy and literature (he wasn’t much impressed), film version of his books (he hated the Smith/Jones version of Wilt but loved Channel 4’s Porterhouse Blue adaptation) and indeed photography, as he had once been a professional photographer and had pleasingly trenchant views on the subject. (When we came to do the photos, he insisted that I use his own tripod for the purpose of making the above picture, as he wasn’t convinced that mine was up to the task.)

The interview was for the Spanish edition of Elle magazine, as Tom had a strong following in Spain, and he eventually went to live there. He ascribed his popularity in Spain to the surrealism Spanish readers found in his books; but his own offering of an example of ‘typically English humour’, as requested on a Spanish TV interview, did not go down too well. He told the story of a troop of Tommies marching to the front line on the Western Front, and an exchange between a young soldier and a sergeant at a posting on the way. ”Ere, Sarge, when do we get to have a rest, been marching all day!’ ‘Don’t worry son, you’ll be dead in half an hour’.

My recollection of the day has a kind of glowing quality: it’s not often you an encounter someone whose work you love and in whom you discover someone who feels like a friend. He struck me much as he appears in the photo above: elegant, droll, mischievous, and as English as a Tudor manor house. We have lost another great one.

… for The London Column.