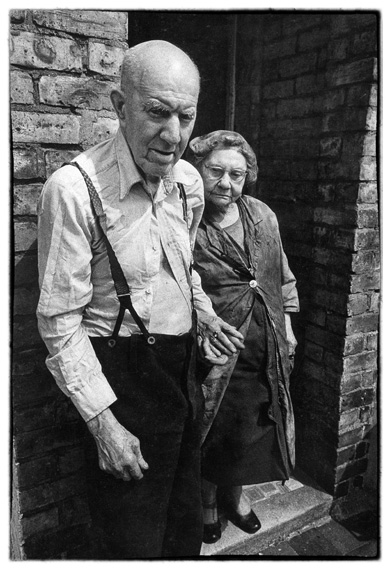

Old couple facing eviction. Photo: Dave Hendley, text: David Secombe.

Posted: November 16, 2012 Filed under: Housing, Street Portraits | Tags: Dave Hendley, Digital Gap, Fulham eviction Comments Off on Old couple facing eviction. Photo: Dave Hendley, text: David Secombe.Overheard pub conversation:

Everyone’s got an uncle Bill. And everyone’s got just one picture of him. Uncle Bill died before you were born. The photo is your mum’s, taken on a trip to Hayling Island when she was a girl. And she shows you this photo, a tear at the corner of her eye, ‘That’s your Uncle Bill’ she says. And she hands you a tiny black and white picture of a man in a suit standing in the middle of a field. That’s your Uncle Bill. Well, it was my Uncle Bill. Who was called Norman. Your Uncle Bill was probably called Cliff. Or Lance.

In the final of the series of Dave Hendley’s rediscovered 1970s photos, this image shows an elderly couple outside their house in Fulham; they were facing eviction from their home after living there for decades. That is as much as I can tell you about the facts of the picture; Dave doesn’t know what became of them or the house itself (if it wasn’t flattened for redevelopment, it is probably now one of those candy-coloured terraced houses that go for over a million pounds). I’d like to know the full story, but perhaps it’s as well I don’t. I imagine the outcome was shabby and depressing: the early 1970s was not a glorious era for social housing in London.

Dave’s photographs this week are fragments of a lost career, and these pictures only exist because he left some old prints at his mother’s house. I don’t know why Dave felt compelled to chuck his old negatives, but he was young when he did it and perhaps didn’t reckon on their value as a permanent record. Now that almost all photographs exist as pixellated images that never get preserved as hard copy, it is sobering to consider the implications for the future. Dave ditched his negatives and got old enough to regret it, but fine prints were (accidentally) preserved. Today’s toy-like cameras make images that are no more durable than an ice sculpture. Photography is becoming utterly ephemeral: you aren’t creating a graven image, you are generating a string of code. Then, a bit later, maybe you get short of space on a memory card so you ditch a few images you don’t think you’ll need, or you forget to back them up, or the hard drive they were on went down … you won’t recover those pictures in anyone’s attic, they are gone. The future is bright and shiny and cares not for the past. Even those of us still using film wince at the price of ‘traditional’ materials: posterity carries a premium. What did Uncle Bill look like again?

In St. James’s Park. Photo: Dave Hendley, text: David Secombe.

Posted: November 15, 2012 Filed under: London Types, Parks, Street Portraits | Tags: Andre Kertesz, Dave Hendley, David Hockney, Elliott Erwitt, Entertaining Mr Sloane, Harold Pinter, Joe Orton, Robert Frank, The Servant Comments Off on In St. James’s Park. Photo: Dave Hendley, text: David Secombe.St. James’s Park. © Dave Hendley 1973.

Photography is concerned with appearance rather than truth, and occasionally, one comes across a photograph so mysterious that one is stumped for any sort of comment. One thinks of the Andre Kertesz photo of a shadow behind glass on a balcony in Martinique; of Robert Frank’s picture of a girl running past a hearse and a street sweeper on a drab London street; or Elliott Erwitt’s shot of tourists in a Mexican charnel house, all acknowledged masterpieces. I think the above photo by Dave Hendley has a similar power. Dave offers no insight: he shot it quickly with his Leica as he walked past the men, then moved along before they had time to register that he had taken their photo (‘I was more ruthless back then, I don’t stick my camera in people’s faces any more’.) But it invites speculation, so I am going to offer mine.

There are few clues in Dave’s photo as to the exact period, but somehow we know it belongs to the past: in fact, it is the early 1970s – but it evokes a time slightly earlier than that. I am reminded of the ‘black and white’ 1960s, the lost era of Victim, Pinter’s The Servant, and, especially, Joe Orton’s Entertaining Mister Sloane: a world of furtive encounters afforded a desperately genteel gloss (“the air round Twickenham was like wine”). But I don’t know whether my interpretation is correct and it probably isn’t. More than one photographer has got into trouble because a photo suggested something about its subjects that was misleading or even libellous. Whatever the reality, the picture is simultaneously comic, poignant and slightly disturbing. The sharply assessing gaze of the man on the left is unnerving enough, but I find myself worried by the man on the right, his too-tight tie and his inscrutable smile somehow just wrong. (I am also reminded of this painting.)

As with the photo we ran yesterday, this photograph is a precious survivor of a cull of Dave’s early work which the photographer carried out with youthful ruthlessness. That was many years ago and, needless to say, Dave now regrets this; fortunately, this image survived as a print which Dave recently discovered in his mum’s attic.

… for The London Column.

See also: Welcoming Smiles, Robert Graves.

Robert Graves visits London and wishes he was back in Deya. Photo: Dave Hendley, poem: Tim Turnbull.

Posted: November 13, 2012 Filed under: Bohemian London, Literary London | Tags: Dave Hendley, Deya Mallorca, Robert Graves, Tim Turnbull, Transit Van Comments Off on Robert Graves visits London and wishes he was back in Deya. Photo: Dave Hendley, poem: Tim Turnbull. Robert Graves at County Hall. © Dave Hendley 1973.

Robert Graves at County Hall. © Dave Hendley 1973.

Sic Transit Gloria Mundi by Tim Turnbull

All aboard now, you children of Demeter,

sling up your canvas haversacks and bedding

on the roof-rack, load the plonk and bread in,

and scrunch into the battered Ford twelve seater.

Discard your wooly hats and your windcheaters;

the weather’s always sunny where we’re heading.

Sing, as if a festival or a wedding

were the destination. Fear won’t defeat us

on our way. Pass the carafe of sangria

as we speed on through the brilliant foothills

of the island. Love and wine make us brave

in face of our enemy, so that we are

exultant first, resigned, and lastly tranquil

on the minibus that bears us to our graves.

… for The London Column. © Tim Turnbull 2012.

David Secombe:

This week we feature some photos from Dave Hendley‘s 1970s archive; I say ‘archive’, but in fact the ones we are running were rescued from Dave’s mother’s attic, and are survivors of an ill-advised cull that Dave made of his work some decades ago. The photo above was taken for The Times; a photo call at an event to honour Graves, who looks massively uncomfortable – which is perhaps unsurprising, given that he hated to leave his beloved home in Deya, Mallorca for any reason whatsoever.

Graves’s tomb, Deya, Mallorca. © David Secombe 1990.

A Haunted Bus. Photo: David Secombe, text: Andrew Martin.

Posted: November 2, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Literary London, Tall Tales, Transport | Tags: haunted bus, L.P. Hartley, Walter de la Mare Comments Off on A Haunted Bus. Photo: David Secombe, text: Andrew Martin.Strand, looking towards Temple Bar. © David Secombe 2010.

An attempt at Putting on a Brave Face

In A Visitor from Down Under by L.P. Hartley, which was published in a collection called The Ghost Book, edited by Walter de la Mare in 1932, we are on the top decl of an open-topped bus ‘making its last journey through the heart of London before turning in for the night’. The loquacious bus conductor encounters a silent, pale passenger with hat pulled down and collar up. ‘Jolly evening,’ says the conductor. (He is being ironic; it is wet and foggy.) There is no reply from the passenger, who holds up his fare between the fingers of stiff, apparently immobile fingers. The conductor takes the money and goes back downstairs. Later, the mysterious passenger is not there. The conductor never saw him come down the stairs, but he rationalises the situation with a very good example of sceptical wishful thinking: ‘He must have got off with that cup-tie crowd’.

From Ghoul Britannia by Andrew Martin, published by Short Books. © Andrew Martin 2009.