Ten Old Men.

Posted: May 27, 2014 | Author: thelondoncolumn | Filed under: Eating places, London Types, Pavements, Shops, Street Portraits, Transport | Tags: bowls, David Secombe, Kings Cross, old geezers, outdoor chess, Tim Marshall, Victoria Way, Woolwich | Comments Off on Ten Old Men. Woolwich. © David Secombe 1998.

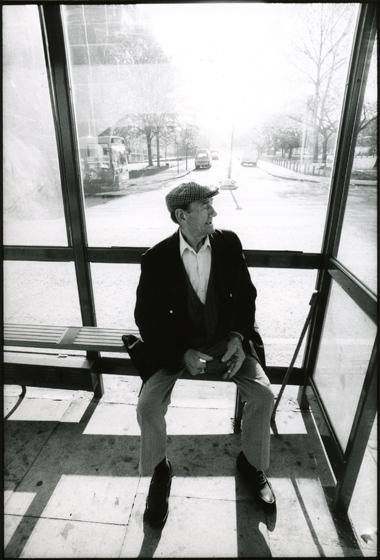

Woolwich. © David Secombe 1998.

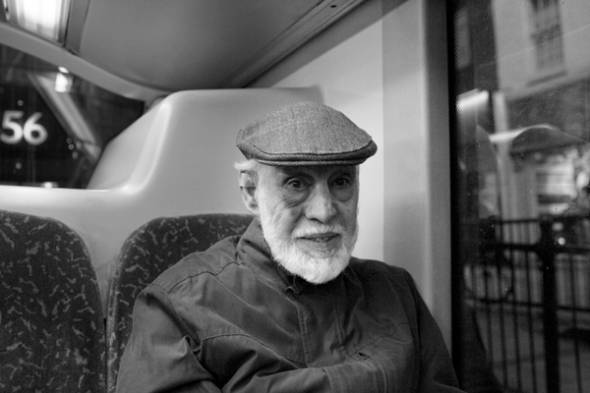

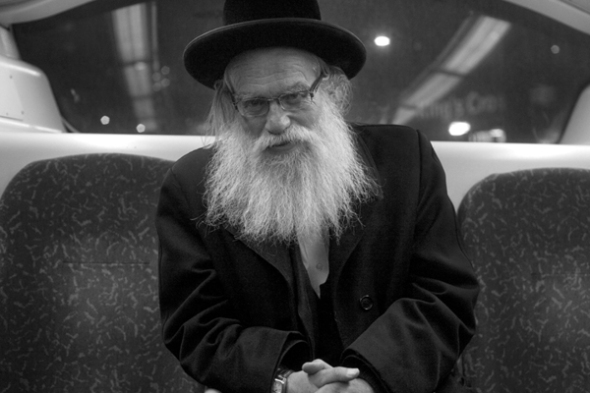

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

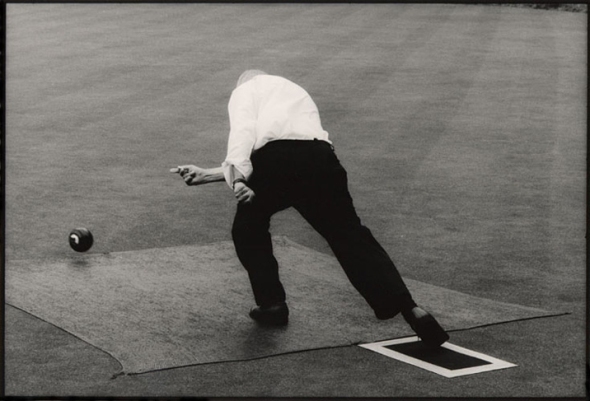

Finsbury Circus. © David Secombe 1998.

Finsbury Circus. © David Secombe 1998.

Clapham Common. © David Secombe 1998.

Clapham Common. © David Secombe 1998.

Spitalfields Market. © David Secombe 1990.

Spitalfields Market. © David Secombe 1990.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

Charlton. © David Secombe 1997.

Charlton. © David Secombe 1997.

See also: 38 Special, King’s Cross Stories, Underground, Overground, Deep South London, Spitalfields Market, Park Life, Ten Imperatives.

The Riverine Strand.

Posted: May 12, 2014 | Author: thelondoncolumn | Filed under: Architectural, Bohemian London, Churches, Housing, Literary London, Vanishings | Tags: Adelphi Terrace, Bob Dylan, Gordon's Wine Bar, John and Robert Adam, oscar wilde trial, Peter Ackroyd, Samuel Pepys, Savoy Chapel, Savoy Hotel, Subterranean Homesick Blues | 2 Comments

Royal Society of Arts, Robert St., Adelphi. © David Secombe 2010.

Royal Society of Arts, Robert St., Adelphi. © David Secombe 2010.

David Secombe: Thirty years ago, I accepted an assignment to illustrate a book of ‘London Walks’; I might have approached this task with more enthusiasm if I hadn’t known that I was offered the brief because the publisher didn’t have the money to pay the author’s preferred photographer. I lost my own copy of the finished item long ago, but recently came across one whilst helping my girlfriend clear an elderly aunt’s house. Looking at it now, it’s obvious that it was a formative experience for me, and that my photos were terrible. In an attempt to expiate former sins, this is the first of two posts revisiting the territory in a bid to see if a grizzled hack can improve upon a callow youth.

On a wet evening last week, I traced the steps of the ‘Riverine Strand’ walk in the company of TLC contributor and bad wine specialist CJ of the Sediment blog. We met outside Gordon’s Wine bar at the bottom of Villiers Street, both of us soaked through and longing for a glass of anything a notch above foul. Gordon’s advertises itself as ‘London’s oldest wine bar’, and it remains an atmospheric place to drink, although it has become more of a corporate playground in recent years. On this occasion our way to the bar was barred by thronging suits, which is why this piece lacks a picture of the vaulted cellar which is Gordon’s USP. We moved on …

York Watergate. © David Secombe 2014

Opposite Gordon’s is a surviving fragment of the lost, pre-Embankment riverside landscape that once constituted this area: York Watergate, landing for York House, a palazzo which bordered the river for over 500 years. York House’s final, broke, owner, George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, flogged it to developers for thirty grand. As Wikipedia gelidly states: ‘He made it a condition of the sale that his name and full title should be commemorated by George Street, Villiers Street, Duke Street, Of Alley, and Buckingham Street. Some of these streets are extant …’. For CJ’s benefit I pointed out that Samuel Pepys lived in a couple of houses on Buckingham Street, and that he also lived in the building where Gordon’s is now. CJ observed that it was still raining.

Lower Robert Street, Adelphi. © David Secombe 2014.

Lower Robert Street is an odd, subterranean thoroughfare that runs through what was once the undercroft of Adelphi Terrace, the centrepiece of the Adam Brothers’ Adelphi development. From The Encyclopedia of London:

In 1867 the Adelphi vaults were ‘in part occupied as wine cellars and coal wharves, their grim vastness, a reminder of the Etruscan Cloaca of old Rome’. Here, according to Tombs, ‘the most abandoned characters have often passed the night, nestling upon foul straw; and many a street thief escaped from his pursuers in these dismal haunts before the introduction of gaslight and a vigilant police’.

Dickens has David Copperfield wandering through this vanished maze, ‘a mysterious place with those dark arches’, which we can assume was an autobiographical reference. When I visited Lower Robert Street in the ’80s, for the purpose of illustrating the guidebook, it was still possible to see a dark courtyard beyond an iron gate: the basement of an Adam townhouse, seen from the POV of Victorian low-life … but that gate is bricked up now. (I dilated upon this factoid to an increasingly glazed CJ as drops of rainwater fell from his rimless spectacles.)

Above, the Adam houses reportedly were – as the houses that remain still are – a toy-town vision of elegance and grace. Of the Adelphi Terrace, E.V.Lucas wrote in 1916: ‘The Adelphi is still a favourite abode of men of letters, for it is central yet retired, and the brothers Adam planned rooms of peculiar comfort’. David Garrick, Richard D’Oyly Carte, Bernard Shaw, Thomas Hardy, all lived there, making it a sort of riverside version of The Albany.

Collcutt & Hemp Adelphi, riverside frontage. © David Secombe 2014.

Collcutt & Hemp Adelphi, riverside frontage. © David Secombe 2014.

Adelphi Terrace was demolished by London County Council in 1936 and replaced by Collcutt and Hemp’s vast Deco block. The Adams’ Adelphi was the first neoclassical building in London, whereas Collcutt and Hemp’s edifice – grotesquely named ‘Adelphi’ – has been described by Ed Glinert (in The London Compendium) as ‘London’s most authentic example of totalitarian 1930s architecture’. Like Bush House at the other end of the Strand, it is a permanent reminder of loss, of a wrong inflicted upon the city. (NB: we are currently working on a survey of Boris Johnson’s skyscraper-nurturing programme.) In 1951, London County Council installed a plaque on one of the pillars of the ‘new’ Adelphi to commemorate the one they had connived to destroy. (The photo at the top of this post is of the Adam house which remains on Robert Street, facing Collcutt and Hemp, home to the Royal Society of Arts.)

Savoy Way. © David Secombe 2014

At this point, CJ wanly suggested going for a drink at the Savoy; but I reminded him that the last time we did that was five years ago, when both of us had money. Instead, we contented ourselves with a cursory inspection of the hotel’s rear quarters, a paragon of rationality, clad in the glazed tiles the Victorians reserved for only the filthiest urban environments.

At Oscar Wilde’s first trial, the following exchange took place between prosecution witness Charles Parker and prosecutor Charles Gill:

PARKER: Subsequently Wilde said to me. ‘This is the boy for me! Will you go to the Savoy Hotel with me?’ I consented, and Wilde drove me in a cab to the hotel. Only he and I went, leaving my brother and Taylor behind. At the Savoy we went first to Wilde’s sitting room on the second floor.

GILL: More drink was offered you there?

PARKER: Yes, we had liqueurs. Wilde then asked me to go into his bedroom with him.

(In an early draft of The Importance of Being Earnest, a solicitor arrives to remove Algernon to Holloway Prison for non-payment of restaurant bills at the Savoy, whereupon Algie retorts: ‘I am not going to be imprisoned in the suburbs for dining in the West End. It is ridiculous.’ Prior to his first trial, Wilde found himself held on remand at Holloway.)

It is tempting to imagine Oscar and Bosie hustling rent boys past the laundry bins and crates of vegetables on Savoy Way. CJ wondered whose laundry the gent in the photo might be carrying.

Savoy Chapel, Savoy Lane. © David Secombe 2014.

Adjacent to the Savoy stands one of those anomalous bits of medieval London marooned amongst anonymous offices. Savoy Palace, a vast 13th Century manor, once sprawled across the foreshore here; the Palace was entirely destroyed during the Peasants’ Revolt but the chapel was later rebuilt as part of Henry VII’s Savoy Hospital, of which it is now the only survivor. I don’t know whether Oscar and Bosie ever came here to ‘cool [their] hands in the grey twilight of Gothic things’, but this happens to be the spot where another Savoy resident, the newly-electric Bob Dylan, telegraphed Subterranean Homesick Blues for D.A. Pennebaker’s camera, as Allen Ginsberg and Tom Wilson loitered meaningfully in the background.

CJ and I emerged from Savoy Lane onto the Strand whereupon it started raining again, so we redoubled our efforts to find a sane place to drink. Dodging umbrellas and puddles by the corner of Waterloo Bridge, we chanced to see Peter Ackroyd alight elegantly from a cab and dive into a Tesco Express. We thought of waiting to see what the biographer of London would do when he emerged, entertaining the wistful hope that he might pop into Maplin’s for some fuses or a remote-controlled helicopter … but my boot was leaking, so we went to the Lamb and Flag, where we stood outside and drank our beers in the rain.

© David Secombe … for The London Column.

See also: A short walk down the Old Kent Road, Four streets off Hockley Hole.