Two Men And A Dog.

Posted: August 30, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Dereliction, The Thames, Vanishings, Wildlife | Tags: 80s Britain, 80s Docklands, Battersea Dogs Home, Bill Pearson, gentrification, south-east London, Stephen Watts poet 2 Comments© Bill Pearson 1982/85

Late August ’87 by Stephen Watts:

Saturday. Afternoon.

Thunder on the Greenland Dock.

A few kids. Wet sand. Fishing.

All of us feel the vatic lack.

Girders. Cranes. New roads.

Bright sciatic colours. Cans.

Concrete. Cables. Coiled wire.

Flesh still curt to our bone.

Autumn thunder on the Greenland

Dock. Suddenly – houses rearing up.

That pall of human indifference.

Heart of the heart ripped out.

Yellow air. Pipes of cloud.

A sky that’s been lifted from Bihar.

Houses with archways of walled wood.

Our lives. A crushed heat of air.

Cranes. Wet sand. Girders.

The kids laugh. And then scatter.

Dear body. The poor in their lack.

The rich in their whorl of languor.

© Stephen Watts

Bill Pearson writes:

I moved to New Cross Gate over the Easter weekend, 1981. My only previous experience of living in the big city had been a few years at Kingston upon Thames, very different in all respects to inner city south-east London. Exploring the new area I discovered empty, desolate docks and rundown industrial areas that reminded me of my homeland in the North of England. It was the early days of Thatcherism, before the Falklands War, before the inner city riots, and before the Miners’ Strike, when Thatcher was still the most unpopular Prime Minister there had ever been.

© Bill Pearson 1982/85

My local Desolation Row was Surrey Docks – re-generated as Surrey Quays – but on walking and cycling trips I discovered the run down warehouses of Shad Thames (which still smelled of the spices they had once stored), Limehouse Basin, Wapping and the Isle of Dogs, which looked like a war zone. I remember rummaging around a warehouse in Wapping one day and hearing a roaring noise on the floor below. I rushed along to see what it was and discovered that the place had been set on fire by some local kids.

© Bill Pearson 1982/85

The absent other in all of these photographs was Mr. Charles Fox. A Battersea Dogs Home graduate, selected for his fetching smile, his hairy ears and his endearing determination to escape from the Home by digging through the concrete floor. His name was chosen because nobody in our shared house was prepared to have the utility bills under their names, so Charlie the dog ended up taking responsibility for everything. He never seemed to mind. At the Post Office I would occasionally be asked, “are you Mr Fox?” – and when people from the utilities phoned up wanting to speak to Mr Fox and we would invariably say “He’s unable to speak at the moment”.

© Bill Pearson 1982/85

Charlie and myself covered a lot of miles on our walks. Sometimes I would carry my Canon AE1 and sometimes I would take my Bolex movie camera and sometimes I wouldn’t take either because I couldn’t afford any film. On these urban forays, I often encountered a fellow rambler who turned out to be another newcomer to south-east London, a political exile from Soweto who had wound up living on the Pepys Estate in Deptford. Not that I knew this at the time: I only learned the identity of Chief Dawethi a quarter-century later, when Chief and I found ourselves sharing an office. Sharing our reminiscences of living in south-east London in the early 1980s, we discovered that we were the ghosts on each other’s travels. I mentioned that I took a lot of photographs back then, and it was Chief’s suggestion that people might be interested in those images, as the area had since changed beyond recognition. Chief’s insight encouraged me to dig out the negatives and study them with fresh eyes.

© Bill Pearson 1982/85

Looking at them now, they appear as remnants of a lost world. ‘There is nothing more recent than the distant past’. It seemed unthinkable in the early 1980s that the purlieus of east London could ever become desirable, let alone exclusive. Yet the areas seen in these pictures is today the playground of those who profited from the sale of England; those inhabitants of the soulless apartments that are ruining the London skyline. Even Chief’s old stamping ground, the Pepys Estate, is home to Aragon Tower, one of the most up-scale of all gentrification projects, a block of high-rise council flats sold off and transformed into luxury riverside dwellings for the few that can afford them.

© Bill Pearson 1982/85

What of Mr Charles Fox? He moved away to York with one of my housemates. We reasoned that he would have a much better life there than on the mean streets of south-east London. I saw him a few times after he moved and he seemed far happier in the North.

Text © Bill Pearson 2013.

© Bill Pearson 1982/85

Heart Of The City by Stephen Watts:

Grey sky. Fifteen cranes swing

between the road and the river.

A darkened ribcage of girders is

Fleshed out with granite slivers.

Slow bursts of cars stream past

and lead rises up to our rooftops.

It eats the aortas of our babies.

Wee kids who spiral at hopscotch.

We have savage material hearts.

Mine hangs just under my shoulder.

There are reds, yellows and ochres

if I think of colour in some order.

It hangs and pumps at my ribcage

as if a blue bag were slung there.

Full with wet fish & blae-berries.

Words – jump off my tongue here.

It is good to dream as dreaming

makes lucid our human potential …

The spiral of blood in our bodies.

Just where it pumps by my nipple.

Sunflowers. Asters. Fuchsia.

Whatever their colours they seem

held by tight and straitened stalks.

The sun will crash from its beam.

Too close to the savaged heart.

We live in the heart of this city.

Cranes that swing out on the dark

measure our hearts without pity.

© Stephen Watts.

On the South Bank. (1)

Posted: August 6, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Artistic London, Monumental | Tags: london civic space, southbank skate park, The Southbank Centre Comments Off on On the South Bank. (1)National Theatre. © David Secombe 2010.

Brutalist architecture has never been popular in Britain. The garden, the milk float, the net curtain, all work to alienate the British sensibility from the modernist, and especially the Brutalist, vision. We don’t care how pure its aesthetic is. We like things Nice.

Maybe the one exception is the good old South Bank. For some reason, despite decades of controversy, two murders, and several refits and remodellings, this complex of buildings is that genuine thing, beloved of the people. Unpromising as one may think it looks (though it is now dotted all over with bright structures, a giant yellow stairway, a turquoise Mexican place in shipping containers, pink things, green bits; they do certainly brighten it up). This is by accident as much as design. Maybe familiarity. Maybe proximity to Tate Modern. Maybe the development of Gabriel’s Wharf and that whole stretch of the river into something a little more friendly. Partly the skateboarders, who just seem to exist alongside everything else, whose thwack thwacks have followed us along that path by the river since the seventies. Certainly the restaurants: people always want something to eat, and the current proposed redevelopment is essentially an opportunity to expand on this.

At just that point, it stops being accident and becomes something more sinister. The space, rejuvenated as it is, has felt increasingly managed (that is, filled with things to be bought) for the past span of years. This is in keeping with a trend, as civic space becomes more and more tied to retail; we are forgetting how to occupy a city without buying, without being told what to look at. If this plan goes ahead, the stretch of river we love most will end up like the renovated Brunswick Centre, with added Thames.

But the Brunswick doesn’t incorporate two of Britain’s most important cultural venues – or the Thames. There is a debate that Londoners (particularly; but also the whole country) need to have about what kind of shared space this complex is supposed to be – who is it for? what is it for? what do we value about it? what do we want it to be like? And, if nothing else, we appear now to be beginning to have that debate (this link is the most informative article we’ve seen on the subject).

The South Bank is important on a personal level. Many of us – most of us, in London – have played out our lives with it as a backdrop. Much as it pains us to admit it, Richard Curtis got that much right; every new relationship seems to have a South Bank moment, and serendipity multiplies there. You meet people, you see things, you get some space to contemplate the sky, you feel the proximity of the physical river, suddenly London feels open and mysterious. But serendipity only happens if you’re left alone to find it. The existing Southbank Centre has more than enough cafés, about 2000% more than ten years ago, and we liked it even then. (Very fond memories of the unassuming old canteen, going back further.) It has been that rare thing: a public space where one can feel private.

These shop-heavy proposals – necessitated by the desperate need for funding to maintain ever-growing levels of activity – will transform the area into yet another crowdfuelled, corporatised zone (art needs people; corporations need crowds). They will gut the Festival Hall embankment in the way that the Royal Opera House extension (also paid for by shiny shops) eviscerated Russell Street. No one can argue that the Royal Opera extension didn’t effectively kill the life (as distinguished from the shopping and eating) of the eastern end of Covent Garden Piazza; and you only have to look at what has been done to Spitalfields and Borough markets in the past few years to be afraid for the South Bank.

Aside from which, everyone seems to have forgotten a principle that was voiced by the influential architect Cedric Price (who designed a radical overhaul for the South Bank in 1983, complete with giant ferris wheel). He said that cities and buildings should never be empty, but nor should they ever be full. For all the recently-added ‘lifestyle opportunities’, this stretch of embankment has been one of the few areas left in London that retains some of this balance; and it’s going.

This is a big thing to say, and it is the crux of the debate the nation needs to have about the South Bank. (And indeed London.) The Southbank Centre has apparently got all kinds of educational remits to fulfil, and outreach, and developing the audiences of tomorrow, and family-friendly holiday activities to lay on, and tourists to first attract and then cater for, and the developments are partly to enable all of this. They’re also, to create badly-needed space for existing facilities: the Poetry Library, for one. Billy Bragg wrote compellingly the other day about the needs of performers, and the projects he describes that are going on at the Southbank Centre are inspiring. Itislovely to go there and have a roof garden. Both of your correspondents here love the South Bank: we use the centre constantly and depend on it hugely. But none of that means the developments in their current form – new shops and restaurants, an obstructive building in the middle, an even more ruined skyline over the river, a giant glass box squatting on top of everything, put through at speed and not consulted on – look like improvements to the actual city. (Sir Nicholas Hytner may have a point.) It’s time to stop, take a breath, have the conversation. This has been as good as said by architects who could have pitched for the contract, but didn’t. As the Architect’s Journal reported:

Bennetts Associates had already withdrawn from the competition, claiming that it had too much work and that it had ‘reservations about the brief’ (see AJ 20.09.2012). Rowan Moore, writing in the Observer, also raised concerns about the ‘commercially-led’ plans which he said could ‘make the Southbank Centre resemble Terminal 5 or Canary Wharf or any moderately upmarket shopping mall.’

After the Tories won the 1951 election, they prioritised the destruction of the Festival of Britain site, for ideological reasons. The current government’s attitudes both to the arts and to public space, similarly ideological, have put institutions large and small under pressure to prove they have a right to exist (you earn the right by making money). The current proposed Southbank scheme is thus about to act out the contemporary version of this philistinism, and the fact that it is presented in the language of ‘inclusivity’ makes it more chilling.

This idea of inclusivity is being underpinned by branding, some of it quite subtle, and the brand seems increasingly personality-driven. Artistic Director Jude Kelly is the driver of these developments, and indeed of the whole ongoing ‘revitalisation’ of the centre. She has made herself admirably available to defend the proposals, and her vision, but the danger is that the whole vision for the South Bank feels like a personal vision. If one wants an ice cream in the interval at the Festival Hall, one even buys a ‘Jude’s Ice Cream’! (The franchise is Minghella.) ‘Southbank Centre’, having already joined up the words South and Bank, has now dropped ‘The’ from its name – turning it from a place into a brand – Southbank Centre – rather as if it were a restaurant or shop. It begins to feel like a sort of Boden or Orla Kiely cultural space, where middle class people (because we are all middle class now) are safe to consume culture en masse along with our pizzas, noodles, and extra-large caramel lattes. But where’s the space for the genuine, austere surprise ? The one no one could plan for you?

We know times have changed – we certainly do know it – but if this blog post is anything, it’s a plea for a deep breath and a deep look at what things really mean. And we’ve barely even mentioned the skateboarders.

We’ll be posting the rest of the week with pictures and impressions – poems, not polemics – of the South Bank and the people who use it.

© Katy Evans-Bush

Hoarding opposite National Theatre. © David Secombe 1982.

Arthur Machen’s Hill of Dreams.

Posted: July 4, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Bohemian London, Fictional London, Literary London | Tags: Arthur Machen, Battersea, Hill of Dreams, pipe smoker Comments Off on Arthur Machen’s Hill of Dreams.Tennyson Street, Battersea. Photo © David Secombe 1982.

From Hill of Dreams, Arthur Machen, 1907:

It was not till the winter was well advanced that he began at all to explore the region in which he lived. Soon after his arrival in the grey street he had taken one or two vague walks, hardly noticing where he went or what he saw; but for all the summer he had shut himself in his room, beholding nothing but the form and colour of words. [. . .]

Now, however, when the new year was beginning its dull days, he began to diverge occasionally to right and left, sometimes eating his luncheon in odd corners, in the bulging parlours of eighteenth-century taverns, that still fronted the surging sea of modern streets, or perhaps in brand new “publics” on the broken borders of the brickfields, smelling of the clay from which they had swollen. He found waste by-places behind railway embankments where he could smoke his pipe sheltered from the wind; sometimes there was a wooden fence by an old pear-orchard where he sat and gazed at the wet desolation of the market-gardens, munching a few currant biscuits by way of dinner. As he went farther afield a sense of immensity slowly grew upon him; it was as if, from the little island of his room, that one friendly place, he pushed out into the grey unknown, into a city that for him was uninhabited as the desert.

At 11.30 a.m. (UK) today, Thursday 4 July, Radio 4 is broadcasting a documentary about Arthur Machen and his ‘disturbing’ visions of a world beyond our own.

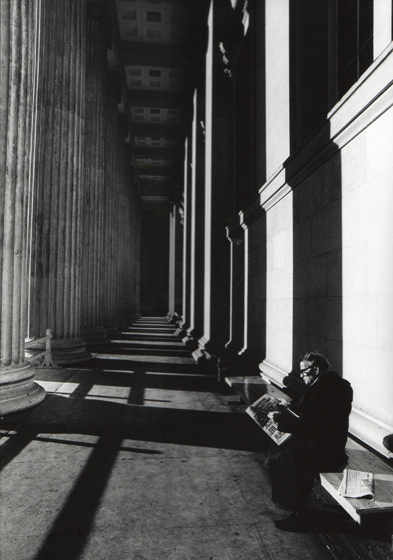

The British Museum Reading Room

Posted: July 1, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Literary London | Tags: British Museum Reading Room, Louis MacNeice Comments Off on The British Museum Reading RoomPhoto © David Secombe 1988.

The British Museum Reading Room by Louis MacNeice, 1939:

Under the hive-like dome the stooping haunted readers

Go up and down the alleys, tap the cells of knowledge –

Honey and wax, the accumulation of years …

Some on commission, some for the love of learning,

Some because they have nothing better to do

Or because they hope these walls of books will deaden

The drumming of the demon in their ears.

Cranks, hacks, poverty-stricken scholars,

In prince-nez, period hats or romantic beards

And cherishing their hobby or their doom,

Some are too much alive and some are asleep

Hanging like bats in a world of inverted values,

Folded up in themselves in a world which is safe and silent:

This is the British Museum Reading Room.

Out on the steps in the sun the pigeons are courting,

Puffing their ruffs and sweeping their tails or taking

A sun-bath at their ease

And under the totem poles – the ancient terror –

Between the enormous fluted ionic columns

There seeps from heavily jowled or hawk-like foreign faces

The guttural sorrow of the refugees.

[The Reading Room is now merely an exhibit, the centre piece of Foster and Partners’ Great Court. The scholars now have to go up the Euston Road to the British Library.]