A Clockwork London. (1)

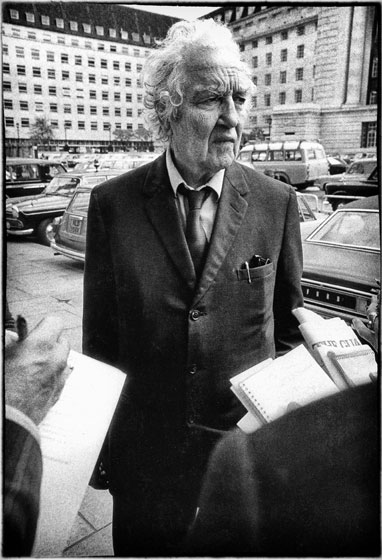

Posted: April 2, 2013 Filed under: Bohemian London, London on film, Pavements | Tags: A Clockwork Orange, Alton Estate Roehampton, Anthony Burgess, Clockwork orange locations, Fahrenheit 451, Stanley Kubrick, Wandsworth roundabout Comments Off on A Clockwork London. (1)Stanley Kubrick on the set of A Clockwork Orange. © Dmitri Kasterine 1969.

From A Clockwork Orange, dir.: Stanley Kubrick, 1971:

……………………………………………………………………..ALEX:

………………………………One thing I could never stand was to see a filthy, dirty old drunkie,

………………………………howling away at the filthy songs of his fathers and going blurp

………………………………blurp in between as it might be a filthy old orchestra in his stinking,

………………………………rotten guts. I could never stand to see anyone like that, whatever his

………………………………age might be, but more especially when he was real old like this one

………………………………was.

(… and with that, Alex and his three droogs start attacking an old tramp lying in the underpass shown below.)

This week’s offering on The London Column is a short series on Stanley Kubrick’s use of London as a giant prop basket. Dmitri Kasterine’s portrait shows the director in his pomp: extravagantly booted, Arriflex to the ready, the world-conquering auteur of 1969. Only 41, he already has The Killing, Spartacus, Lolita, Dr. Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey behind him, an amazing achievement – which might explain why he looks a little weary. But his tiny camera and huge boots suggest the nature of his new project, a film far removed from the 70mm, Cinerama world of 2001. SK’s new one is set much nearer home.

Kubrick’s withdrawal of A Clockwork Orange in the UK – a ban that lasted from the late ’70s until his death – lent the film a mystique for all those British film fans unable to see it. I bought a pirated VHS tape of it (£15 in 1991) from a stall in Greenwich market and was, inevitably, hugely disappointed. A friend who watched it with me commented ‘Whatever I expected, this isn’t it.’ It is prescient in many ways, especially in its depiction of the dissemination of sexualised imagery (even if it exhibits some old-world sexism in the process), but time has not been kind to the Kubrick/Burgess brand; Kubrick’s other films of the ’60s and ’70s stand up much better. But it remains a terrific showcase for 1960s architecture.

Kubrick shot A Clockwork Orange quickly and cheaply in found locations within easy reach of his Hertfordshire lair. Carefully chosen new builds in Wandsworth, Uxbridge, Sydenham, West Norwood, Borehamwood and, most famously, Thamesmead, served as ready-made cycloramas for the director’s realisation of Burgess. The film’s opening atrocity is committed by Alex and co. in an underpass beneath Wandsworth roundabout. Like the Westway and the approaches to the Blackwall Tunnel, the roundabout and its environs constitute a sort of Birmingham in London: an imposing 1960s circulatory system just south of Wandsworth Bridge, complete with truncated and pointless autostrada carrying traffic to and from Wandsworth Common, where the motorway peters out in despair. (Wandsworth roundabout’s other claim to cultural distinction is the Sunday in 1973 when, during a furious row with his wife Jill Bennett, John Osborne drove his Mercedes into it.)

The pedestrianised centre of the roundabout is an assemblage of geometric concrete forms, served by brooding, permanently shadowed underpasses: ideal for Kubrick’s purposes and, subsequently, anyone else seeking to create representations of urban anomie. In fact, the association of Brutalist buildings with urban hopelessness has become such a cliché that it is worth noting that A Clockwork Orange pioneered the look. Francois Truffaut had shot Fahrenheit 451 in similar fashion a couple of years earlier, using Roehampton’s Alton Estate as a setting for a future society where the printed word is forbidden; but the dreamy, otherworldly mood of his film is worlds away from Kubrick’s visceral scenario. In seeking a cinematic equivalent for Burgess, Kubrick used Brutalism to create a visual shorthand for future awfulness. One can only imagine the dismay of early seventies architects and civic engineers seeing the finished film, which simultaneously treasures and trashes the well-meaning buildings on show, and explicitly links massed concrete with looming dread.

If Kubrick were making the film now, one wonders what visual cues he would employ. The social idealism of Brutalism has been supplanted now by an aggressively ingratiating public architecture based on consumerism, a landscape pithily described by Owen Hatherley as ‘the post-1979 England of business parks, Barratt homes, riverside ‘stunning developments’, out-of-town shopping and distribution centres.’ Which locations would Kubrick use today? Bromley? Woking, maybe? Corporate faux-vernacular would offer the right look. Saturday night in a modern British provincial town offers ample scope for rape and pillage, the pedestrianised shopping precinct the perfect setting for a spot of ultra-violence. Hell is the walkway between Nando’s and Asda.

Southern underpass, Wandsworth Roundabout. © David Secombe 2012.

… for The London Column.

Jeremy Ramsden.

Posted: January 30, 2013 Filed under: Artistic London, Bohemian London, London Labour, Vanishings | Tags: Brian Griffin, Harry Borden, Jeremy Ramsden, Labyrinth Photographic, Tim Walker 3 CommentsJeremy Ramsden in his darkroom at Labyrinth, Bethnal Green. © David Secombe 2011.

David Secombe:

One of the things that is being lost in our back-lit, screen-bound digital world is the texture associated with older forms of image-making. As someone who became a photographer because I liked the idea of making something, of leaving something tangible behind me, I mourn the gradual passing of the physical photograph: the transparency, the negative and the print.

Traditionally, the relationship between photographers and their printers was not always easy; not every photographer could print their images like Eugene Smith or Don McCullin, and even if they could, they couldn’t always spend hours in the darkroom when they were busy shooting. Some printers would – justifiably – resent having to fix their clients mistakes or deal with photographers who didn’t really know what they wanted their prints to look like. But others took a more lenient view of photographers’ foibles and would, where necessary, give them an informal technical training to go with their prints. And from the mid-1980s,advances in reproduction technology and an increasing acceptance of colour negative film as a serious format for serious photography ushered in a new era of image-making. Professionals were liberated from the unforgiving tyranny of the transparency – more room for manoeuvre after the shoot, more latitude of exposure and expression, a level of freedom previously available only to those who shot black and white. It was in this arena that colour printers like Brian Dowling and Jeremy Ramsden reigned supreme.

Jeremy Ramsden, who died last week, was one of the finest colour printers of his generation. Jeremy could take a frame of anyone’s film and turn it into a work of art on paper. The quality of Jeremy’s work is only partially discernible on a website, because the sheer physical beauty of his prints, their intensity and almost holographic clarity, can only be experienced by personal appointment. Jeremy’s fanatical attention to detail was apparent in the way he would, as a matter of course, produce a variety of prints from the same frame, with each print having its own distinct mood and character. Variations on a theme, if you like, the creation of totally different images from a single piece of film. And when you got your negatives back, you’d see his meticulous notes written on little strips of masking tape affixed to the protective sheets. Jeremy went to these lengths because he cared, because he was an enthusiast for photography. And when you consider the names on his client list – which included the likes of Tim Walker, Elaine Constantine, Harry Borden, Brian Griffin – the breadth of his achievement becomes clear.

Jeremy was Australian (not for nothing was his erstwhile lab in Shoreditch called Outback) and he arrived in London as a merchant sailor in the early 1970s. He knocked around London’s photo scene in a variety of capacities – studio assistant to the likes of Brian Duffy and Angus Forbes, freelancing as a photojournalist (he was a very fine photographer in his own right) and mastering all aspects of the arcane art of colour printmaking. His experiences of the glory days of Soho in the advertising boom of the 1970s and 80s would have made a very interesting book. Jeremy had a stereotypical Ozzie enthusiasm for travel, people and a good story – but, above all, he liked sharing his enthusiasm for the world and how we see it. He was generous with his time and, like our friend John Driscoll, who died last year, he was a champion of photographers. Having Jeremy or Brian or John in your corner was like having a secret weapon; if you had the nod from them, you could breathe a little easier. They knew the score. I always thought it was important to earn the respect of the people who handled my pictures, and I think most photographers would agree – although there were some ‘celebrated’ photographers who relied a little too heavily on the expertise of darkroom staff to produce their meisterwerks. But Jeremy spoke of his clients very warmly, and this was because he was reluctant to print for anyone he didn’t respect; so an unsolicited compliment from Jeremy was worth far more than one from almost any picture editor.

It is hard to write a piece like this without sounding nostalgic or merely old; but it seems to me that apart from the loss of the tactile aspect, the ubiquity of digital imaging has led to the erosion of a social element within photography. I’m not the only one who misses that. It is hard to think of Jeremy not being there to work his magic on a print, to offer his take on it, see the potential of a negative fully realised – and then discuss the competition and swap stories over a pint. A couple of years ago, Jeremy co-founded Labyrinth, a darkroom in the East End which has become a mecca for new and established photographers. Jeremy was full of excitement for the young talents who were bringing their pictures to him, the brave ones who had chosen to render their images on film rather than as pixels on a chip. He was rejuvenated by the challenge and, apart from anything else, it is a tragedy that he will not see his fledglings develop and mature.

He gave a great deal and asked for very little in return. Personally, I owe him a huge amount – and the shock of his sudden passing still hasn’t sunk in. I can’t quite believe it. The industry will feel a lot colder without him. The world will too.

… for The London Column.

Robert Graves visits London and wishes he was back in Deya. Photo: Dave Hendley, poem: Tim Turnbull.

Posted: November 13, 2012 Filed under: Bohemian London, Literary London | Tags: Dave Hendley, Deya Mallorca, Robert Graves, Tim Turnbull, Transit Van Comments Off on Robert Graves visits London and wishes he was back in Deya. Photo: Dave Hendley, poem: Tim Turnbull. Robert Graves at County Hall. © Dave Hendley 1973.

Robert Graves at County Hall. © Dave Hendley 1973.

Sic Transit Gloria Mundi by Tim Turnbull

All aboard now, you children of Demeter,

sling up your canvas haversacks and bedding

on the roof-rack, load the plonk and bread in,

and scrunch into the battered Ford twelve seater.

Discard your wooly hats and your windcheaters;

the weather’s always sunny where we’re heading.

Sing, as if a festival or a wedding

were the destination. Fear won’t defeat us

on our way. Pass the carafe of sangria

as we speed on through the brilliant foothills

of the island. Love and wine make us brave

in face of our enemy, so that we are

exultant first, resigned, and lastly tranquil

on the minibus that bears us to our graves.

… for The London Column. © Tim Turnbull 2012.

David Secombe:

This week we feature some photos from Dave Hendley‘s 1970s archive; I say ‘archive’, but in fact the ones we are running were rescued from Dave’s mother’s attic, and are survivors of an ill-advised cull that Dave made of his work some decades ago. The photo above was taken for The Times; a photo call at an event to honour Graves, who looks massively uncomfortable – which is perhaps unsurprising, given that he hated to leave his beloved home in Deya, Mallorca for any reason whatsoever.

Graves’s tomb, Deya, Mallorca. © David Secombe 1990.

Hockley Hole, AKA Central Saint Martins. Photo & text: David Secombe.

Posted: May 16, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Artistic London, Bohemian London, Public Art, Vanishings | Tags: Back Hill, Central Saint Martins, Common People, Hockley in the Hole, John Driscoll, Johno's Darkroom 2 CommentsBack Hill, 2010. © David Secombe.

From The Fascination of London: Holborn and Bloomsbury, edited by Sir Walter Besant 1903:

The lower part of Saffron Hill was known at first as Field Lane, and is described by Strype as “narrow and mean, full of Butchers and Tripe Dressers, because the Ditch runs at the back of their Slaughter houses, and carries away the filth.” Just here, where Back Hill and Ray Street meet, was Hockley Hole, a famous place of entertainment for bull and bear baiting, and other cruel sports that delighted the brutal taste of the eighteenth century. One of the proprietors, named Christopher Preston, fell into his own bear-pit, and was devoured, a form of sport that doubtless did not appeal to him. Hockley in the Hole is referred to by Ben Jonson, Steele, Fielding, and others. It was abolished soon after 1728. All this district is strongly associated with the stories of Dickens. In later times Italian organ-grinders and ice-cream vendors had a special predilection for the place, and did not add to its reputation.

David Secombe writes:

One might add that in the 20th century, the area described above became associated with the photographic profession: at one time Clerkenwell was said to have more darkrooms and studios per square foot than anywhere else in the world. As a coda to yesterday’s post remembering the great Johno Driscoll, here’s a picture of ‘found art’ posted to the wall of John’s old premises, Holborn Studios, which is now a campus for Central Saint Martins art college. The building is situated within ‘the Hole’ – although the site of the bear-pit itself is now occupied by the pub opposite, The Coach and Horses. (Allegedly, the pub once afforded access to the Fleet river from its cellars, providing 18th Century fugitives with an escape route to the Thames.) Somehow, it seems right and proper that one of the most disreputable spots in 16th and 17th Century London should have gone on to be associated with photography, fashion, and art: the favoured trades of chancers, ne’er-do-wells and diamond geezers.

… for The London Column. See also: Little Jimmy, King of Clerkenwell.