London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (1/5)

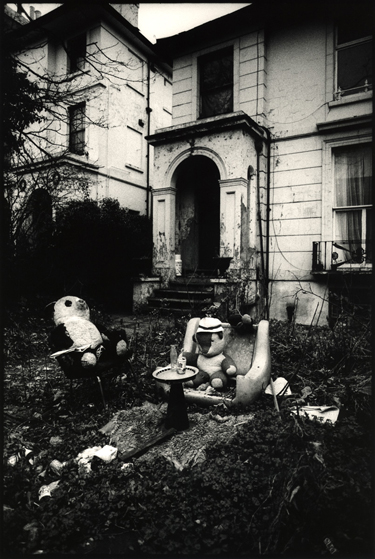

Posted: July 2, 2012 Filed under: Dereliction, Literary London, Vanishings, Wildlife | Tags: Arthur Machen, Camden, Holloway, London Gothic, Peter Ackroyd, tea party Comments Off on London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (1/5)Camden Road. © David Secombe 1987.

From London The Biography by Peter Ackroyd, 2000:

Whole areas can in their turn seem woeful or haunted. Arthur Machen had a strange fascination with the streets north of Gray’s Inn Road – Frederick Street, Percy Street, Lloyd Baker Square – and those in which Camden Town melts into Holloway. They are not grand or imposing; nor are they squalid or desolate. Instead they seem to contain the grey soul of London, that slightly smoky and dingy quality which has hovered over the city for many hundreds of years. He observed ‘those worn and hallowed doorsteps’, even more worn and hallowed now, and ‘I see them signed with tears and desires, agony and lamentations’. London has always been the abode of strange and solitary people who close their doors upon their own secrets in the middle of the populous city; it has always been the home of ‘lodgings’, where the shabby and the transient can find a small room with a stained table and a narrow bed.

David Secombe:

In the midst of our jingoistic Olympic summer, I thought it might refreshing to explore the aspect of London so eloquently evoked by Peter Ackroyd in the passage above. A city of silent yet inhabited houses, anonymous windswept streets, overgrown front lawns, strange objects on the back seats of abandoned cars, forbidding municipal playgrounds, etc. (This is essentially the same territory explored by Geoffrey Fletcher in The London Nobody Knows, and as the last series on The London Column was a revisiting of Fletcher’s book, this one may be seen as a continuation of the same theme.) ‘London Gothic’ is becoming increasingly rare; most of the streets that Arthur Machen thought of as woeful are now exemplars of prosperous gentrification. London is a cleaner, neater place: even King’s Cross is a landscaped zone now. The photo above was taken a quarter of a century ago, and Holloway has come up in the world since then. The specific, shabby London charm that Machen and Ackroyd describe may still be found, but one has to look harder. As a small boy visiting the city from the suburbs, I was amazed by the soft enveloping greyness which made the occasional bursts of colour all the more striking. That quiet visual texture is vanishing, when even municipal housing wears screaming day-glo colours, as 1960s & 70s blocks are clad in blue, yellow, or turquoise panels. London wears its dread in brighter shades these days.

… for The London Column.

The London Nobody Knows – revisited. Photos & text: David Secombe (1/4)

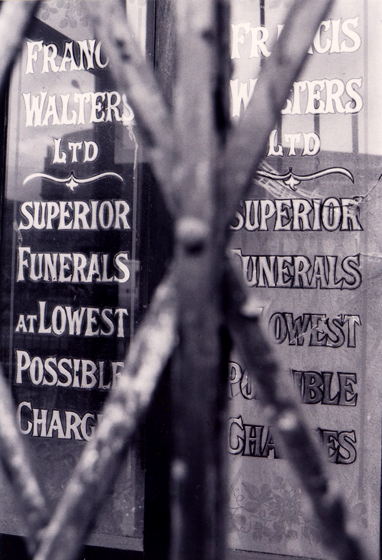

Posted: June 19, 2012 Filed under: Dereliction, Literary London, Shops, Vanishings | Tags: Geoffrey Fletcher, limehouse, superior funerals, The London Nobody Knows, undertaker Comments Off on The London Nobody Knows – revisited. Photos & text: David Secombe (1/4)Limehouse. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

From The London Nobody Knows, Geoffrey Fletcher, 1962:

My chief pleasures in Limehouse are confined to a small area, centering on the church of St. Anne. The undertaker’s opposite the church is a rare example of popular art. Even today, East End funerals are often florid affairs – it is only a few years since I saw a horse-drawn one – but such undertaker’s as [the one in the above photo] must be becoming rare, so it is worth study. It is hall-marked Victorian. The shop front is highly ornate and painted black, gold and purple. Two classical statues hold torches, and there achievements of arms in the window and also inside the parlour. The door announces ‘Superior funerals at lowest possible charges’. On one side of the window is a mirror on which is painted the most depressing subject possible – a female figure in white holding on (surely not like grim death?) to a stone cross and below her are the waves of a tempestuous sea. Inside the shop are strip lights – the only innovation to break up the harmony of this splendid period piece – a selection of coffin handles and other ironmongery and a photograph of Limehouse church. As I looked, a workman, with a mouthful of nails, was hammering at a coffin. An unpleasant Teutonic thought occurred to me that, at this very moment, the future occupant of the coffin might well be at home enjoying his jellied eels . . . Undertaker’s parlours of such Victorian quality must be enjoyed before it is too late. This one mentioned is, I believe, the best in London. People stare through the windows of undertakers – at what? Unless they are connoisseurs of Victoriana there seems to me little beyond the elaboration of terror and a frowsy dread that has no name.

David Secombe:

The shop Geoffrey Fletcher rhapsodised over fifty years ago remains in situ opposite St. Anne’s, but is now derelict. When I took this photo a couple of years ago, it was possible to see the remnants of the shopfront, but a matter of days later the entrance was boarded up and the last remnant of the Victorian throwback that Fletcher described with such relish disappeared from view. This week we are running a small selection of excerpts from Fletcher’s classic, alongside contemporary views of the sights he delineated so lovingly. Fletcher’s book is a kind of requiem for an older, more private city – and although his fears about the fate of many individual buildings proved to be unfounded, Londoners are faced with a new wave of monolithic redevelopment. In our current era of corporate-sponsored ‘regeneration’, the final words of the book seem truer than ever: ‘Off-beat London is hopelessly out of date, and it simply does not pay. I hope, therefore, that this book will be a stimulus to explore the under-valued parts of London before it is too late, before it vanishes as if it had never been. The old London was essentially a domestic city, never a grandiose or bombastic one. Its architecture was therefore scaled to human proportions. Of the new London, the London of take-over bids and soul-destroying office blocks, the less said, the better’.

… for The London Column.

London Facades. Photos: Mike Seaborne, text: Charles Jennings.

Posted: March 16, 2012 Filed under: Dereliction, Shops, Vanishings | Tags: abandoned shops, Charles Jennings, Mike Seaborne, pre-corporate London Comments Off on London Facades. Photos: Mike Seaborne, text: Charles Jennings.Clockwise from top left: Englefield Road, Bethnal Green Road, Willesden High Road, Whitecross Street.

© Mike Seaborne 2005, 2006.

Fag End London by Charles Jennings:

Two geezers in overalls flicking litter into a truck (‘Could’ve bleeding stayed in bed, didn’t know it was only this one’).

Keeping their ends up against the taggers and bomb artists on the main road. ‘That shouldn’t be allowed ’cause they laid out a lot of money’.

You’ve got your haggard local shops, giving out, giving in, ‘Houses & Flats Cleared, Apply Within’, a stupidly optimistic fingerpost.

The coughing of the birds, the single, muted noise of a car driving along in first a block away.

‘Big Reductions on Room Size’, with a tiny old lady picking at some cream-vinyl dining chairs stuck out on the pavement as if they were posionous, a dysfunctional boy pulling at the hair of a girl in a newsagent’s doorway, the sullen rumble of a train. Who’s going to be passing through?

Dead cars, living cars, stuff you do to your car, garages.

Those jaded avenues of small houses, the litter, the small shops, nervy pre-dereliction, the effort to keep up.

The midget shops, the kebabs, the roaming crazies (woman in a tank top scouring the bins: ‘Fucking said to him, “Fucking listen”‘).

This tomb of obscurity.

The dead concrete around the tube station, ruined retail outlets.

Drowning in toxins, grimed-up, catching screams from the estate on the west side, the traffic barrelling to hell on the roundabout.

Sort myself out a nice K-reg Astra.

It’s shy of life, but only because it’s keeling over.

… for The London Column. © Charles Jennings 2012.

Mike Seaborne:

London Facades is a series of photographs about the disappearing face of pre-corporate London. The project is London-wide and embraces a range of different facades, including shops, industrial and commercial buildings and housing.

The pictures are mostly taken in areas of the inner city undergoing regeneration – and in many cases gentrification – and the most suitable subjects are often found on the periphery of such redevelopment schemes where the blight seems more evident than the intentions to renovate or rebuild.