Swansong.

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones 6 Comments Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

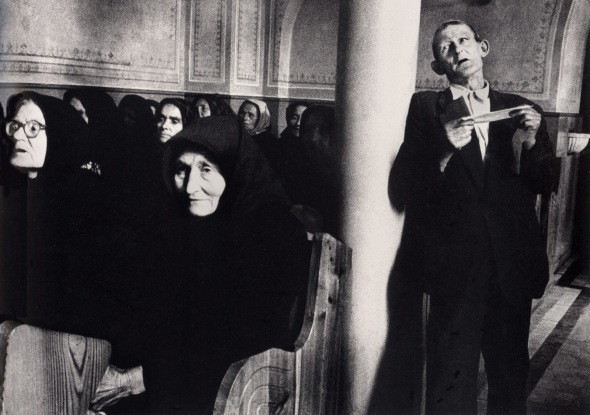

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

Rotherhithe. Photo Geoff Howard, text Charles Jennings (5/5)

Posted: September 7, 2012 Filed under: London Types | Tags: Charles Jennings, Geoff Howard, Rotherhithe Comments Off on Rotherhithe. Photo Geoff Howard, text Charles Jennings (5/5)Brunel Road, Rotherhithe, London, July 1979. © Geoff Howard.

The rest is silence by Charles Jennings:

This car is following me. No, either it’s following me – dark blue Golf – or it’s as lost as I am and just happens to emerge and re-emerge round corners and at the ends of roads and roll silently past me, the driver painstakingly not looking my way but screwing up his brow as he lunges off up another sidetrack which I know will bring him out twenty yards ahead of me. This is paranoia all right, and I’ve only been here 15 minutes.

Another thing: after a lot of ducking and weaving, I shake the car get onto the street that runs down by the river, two apes start following me, cropheads, bomber jackets, you know the sort, bouncers. Didn’t say anything, mark you, just kept their distance 30 feet behind. Nice sunny day, but I still felt that unease. So I jinked behind a litter bin, doubled back round a newbuild block of flats, nipped out on Salter Road, turned round a couple of times, lost them. Close though.

I don’t normally act this way, but Rotherhithe is not on the level. It was a perfect day, breeze blowing, sun shining, operatic clouds billowing up from the south-west, and yet such is its emptiness, the untenantedness, the shortage of humanity around Rotherhithe a lot of the time, that I can’t remember the last occasion I felt so alone in the big city except when I was last down the wrong stretch of Wapping, the sister city across the Thames. Here they were, of course, Wapping and Canary Wharf, I could see them standing golden in the sun on the north side, while kids combed the shingle beach for pounds.

Alone and lost. Just me and ranks of newbuild properties – little three-bedders with oak-effect doors, new wave flatlets topped off with pointless metal triangles and overturned D’s; refashioned warehouses on the river; fake Georgian tenements – once in a while interrupted by a canal or dead creek with tide heights marked in Roman numerals up the side, all doubling back on themselves, leading in and out of nowhere.

Not even any shops to get some sort of bearing, apart from a pair of bolted and shuttered takeaways next to a Stop ‘n’ Shop and the The Compasses pub. I clung to this last for a bit, going round in circles, afraid to lose it and myself again – before I realised that I had to be somewhere else in an hour and a half and that if I didn’t start looking for a way out, I’d never leave in time.

So it was off to the Dan Dare tube station where I thought I’d arrived a lifetime earlier, and back over the scrap of wasteland – where I finally saw a couple of people, trudging into the distance, carrying bags. And then a terrific racking cough, like a bomb going off, and this wrecky old geezer lurches out from a bush and makes for a bench. I was going to hail him, winkle out the secret of Rotherhithe, the two worlds. V-reg cars penned in behind security fences (“Specialist Dogs and Tactics” it said on a notice on one) versus the tough old estates left behind, but then another of those blokes appeared – no. 1 crop, Crombie, pit bull on a string. I thought “Hallo,” like you do, and bunked off quick.

© Charles Jennings.

[Charles’s copy was originally written for The Guardian‘s ‘Space’ supplement and was published in April 2000. As such, it is almost as much of a period piece as Geoff’s photos. D.S.]

Rotherhithe Photographs: 1971-1980 by Geoff Howard is available direct from the photographer at £25.

Rotherhithe. Photo: Geoff Howard, text: Charles Jennings. (2/5)

Posted: September 4, 2012 Filed under: London Types, Pavements, Shops, Street Portraits | Tags: Charles Jennings, corner shops, gentrification, Geoff Howard, London docklands, Rotherhithe, SE16 Comments Off on Rotherhithe. Photo: Geoff Howard, text: Charles Jennings. (2/5)Corner shop, Brunel Road, Rotherhithe, London, July 1974. © Geoff Howard.

Gentrification by Charles Jennings:

Two geezers in overalls flicking litter into a truck (‘Could’ve bleeding stayed in bed, didn’t know it was only this one’). Keeping their ends up against the taggers and bomb artists on the main road. ‘That shouldn’t be allowed ’cause they laid out a lot of money’. You’ve got your haggard local shops, giving out, giving in, ‘Houses & Flats Cleared, Apply Within’, a stupidly optimistic fingerpost. The coughing of the birds, the single, muted noise of a car driving along in first a block away. ‘Big Reductions on Room Size’, with a tiny old lady picking at some cream-vinyl dining chairs stuck out on the pavement as if they were poisonous, a dysfunctional boy pulling at the hair of a girl in a newsagent’s doorway, the sullen rumble of a train. Who’s going to be passing through? Dead cars, living cars, stuff you do to your car, garages. Those jaded avenues of small houses, nervy pre-dereliction, the effort to keep up. The midget shops, the kebabs, the roaming crazies (woman in a tank top scouring the bins: ‘Fucking said to him, “Fucking listen”‘). This tomb of obscurity: drowning in toxins, grimed-up, catching screams from the estate on the west side, the traffic barrelling to hell on the roundabout. Sort myself out a nice K-reg Astra. It’s shy of life, but only because it’s keeling over.

… for The London Column. © Charles Jennings 2012.

Rotherhithe Photographs: 1971-1980 by Geoff Howard is available direct from the photographer at £25.

London Facades. Photos: Mike Seaborne, text: Charles Jennings.

Posted: March 16, 2012 Filed under: Dereliction, Shops, Vanishings | Tags: abandoned shops, Charles Jennings, Mike Seaborne, pre-corporate London Comments Off on London Facades. Photos: Mike Seaborne, text: Charles Jennings.Clockwise from top left: Englefield Road, Bethnal Green Road, Willesden High Road, Whitecross Street.

© Mike Seaborne 2005, 2006.

Fag End London by Charles Jennings:

Two geezers in overalls flicking litter into a truck (‘Could’ve bleeding stayed in bed, didn’t know it was only this one’).

Keeping their ends up against the taggers and bomb artists on the main road. ‘That shouldn’t be allowed ’cause they laid out a lot of money’.

You’ve got your haggard local shops, giving out, giving in, ‘Houses & Flats Cleared, Apply Within’, a stupidly optimistic fingerpost.

The coughing of the birds, the single, muted noise of a car driving along in first a block away.

‘Big Reductions on Room Size’, with a tiny old lady picking at some cream-vinyl dining chairs stuck out on the pavement as if they were posionous, a dysfunctional boy pulling at the hair of a girl in a newsagent’s doorway, the sullen rumble of a train. Who’s going to be passing through?

Dead cars, living cars, stuff you do to your car, garages.

Those jaded avenues of small houses, the litter, the small shops, nervy pre-dereliction, the effort to keep up.

The midget shops, the kebabs, the roaming crazies (woman in a tank top scouring the bins: ‘Fucking said to him, “Fucking listen”‘).

This tomb of obscurity.

The dead concrete around the tube station, ruined retail outlets.

Drowning in toxins, grimed-up, catching screams from the estate on the west side, the traffic barrelling to hell on the roundabout.

Sort myself out a nice K-reg Astra.

It’s shy of life, but only because it’s keeling over.

… for The London Column. © Charles Jennings 2012.

Mike Seaborne:

London Facades is a series of photographs about the disappearing face of pre-corporate London. The project is London-wide and embraces a range of different facades, including shops, industrial and commercial buildings and housing.

The pictures are mostly taken in areas of the inner city undergoing regeneration – and in many cases gentrification – and the most suitable subjects are often found on the periphery of such redevelopment schemes where the blight seems more evident than the intentions to renovate or rebuild.