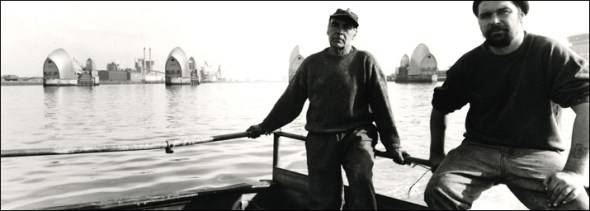

Johno Driscoll. Photo: Tim Marshall, text: David Secombe.

Posted: May 15, 2012 Filed under: London Types, Street Portraits, Vanishings | Tags: Craig McDean, Eamonn McCabe, Elaine Constantine, fine art printing, Johno's Darkroom, Nick Knight, Sean Smith 20 CommentsJohn Driscoll, outside the Horseshoe, Clerkenwell Close, 2011. Photo © Tim Marshall.

David Secombe writes:

Any photographer who came of age in the pre-digital era can still summon up the clammy, vertiginous mix of excitement and fear which attended a trip to the darkroom to review the results of a shoot. Most London labs (invariably located in basements) reeked of fixer and testosterone: some establishments referred to their clients as “the enemy”, and any cock-ups or infelicities on the part of the photographer left the hapless smudger open to mockery, abuse and, it was rumoured, actual physical violence from short-tempered darkroom staff. This added a certain nervous tension to the experience of checking out your film. But there were some noble exceptions to this rule.

John Driscoll, who died on Monday, was the proprietor of the legendary Johno’s Darkroom – black and white only – an establishment supreme of its kind, its reputation resting on John’s brilliance as a printer and warmth as a human being. On any given day from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, a bewildering array of images would pass through Johno’s – haute couture, music, hard news, fine art – but whatever the subject, all John’s prints bore that exquisite, luminous quality which made him the printer of choice to the likes of Nick Knight, Craig McDean, Elaine Constantine, Eamonn McCabe, Sean Smith, and many, many others. His printing technique was matched only by his generosity and enthusiasm for the work of the photographers he admired.

Johno’s was a sort of club for the profession. You’d wait for John to finish your prints, swap notes with other photographers, sneak a look at pictures other people had brought in and inwardly (and occasionally outwardly) remark upon the quality of them. You’d exchange stories and bad jokes with his colleagues Jason and Paul (later it was Barb and Cherie), and glimpse John emerging from the dark now and again to take a call, retouch a print or send someone to the bookie’s with a hot tip and a tenner. When all the rush jobs were cleared, we’d migrate to pubs in pre-gentrification Clerkenwell or Hoxton (John was based in Hoxton Square for much of the early 1990s, and his darkroom was next door to where White Cube stands today), where John had to be forcibly prevented from buying every round. Very often, his wife Barbara – the other half of the Variety double act – would be at the lab, and could usually be persuaded to come out for a drink: much shouting and hilarity and missing of trains home would ensue. Everyone felt good around John, he could energise a room simply by walking into it.

The best photographers went to him because he was the best, but all the bullshit surrounding the profession fell away when you were in his company. Some photographers might be prima donnas in the wider world, but no-one outshone John in his own domain. And it was unwise for, ah, naive photographers to treat John as just some kind of tradesman; more than one photographer was shown the door because John thought his or her work was fraudulent. Yet, for some of his clients, John was prepared to do much more than just turn out lovely prints. Occasionally, John would receive rolls of film from some flailing, desperate young photographer, fearing disaster after a fraught shoot on a big assignment. In a war film, John would have been the cheerful sergeant steadying the nerves of an inexperienced officer: if John was on your side, you were all right. He’d get you through. He was the relief column. There are a number of very successful photographers who have very good cause to be grateful to John. He inspired tremendous loyalty. We weren’t his clients: we were his devotees.

John first went to work in New York around the Millennium. It was at the request of Craig McDean, who had him flown out at the expense of a client as he was the only black and white printer who could do Craig’s pictures justice. He ended up founding Johno’s NY and stayed in the US until the rise of digital eroded the market for traditional printing, retiring to Brighton only a few years ago. Of course, he wasn’t really retired, he was looking to get a darkroom going on the south coast, or a gallery maybe – somewhere where he could share his love of photography and showcase the work of his friends and clients, a place to show “all those wonderful images that need to be seen”.

With grim irony, I learnt of John’s death on the same day as I heard of a new digital camera from Leica: the ‘Monochrom’. It only takes black and white images – the idea is that a digital chip will duplicate the look of the finest black and white photographs. It’s worth stopping to consider the proposition: that a piece of hardware can replace the care and dedication which transforms a negative on a piece of celluloid into a work of art on paper. I can’t see it myself.

I think of John casually producing a box of prints he’d made from my negatives, and asking if I was happy? The prints glowed from within. I was so grateful I wanted to cry. I’d grabbed a few pictures in difficult conditions for a demanding client and he’d turned them into objects of beauty (saving my arse in the process). You can’t replace that with a chip. An age is passing and we are the poorer for it. I grieve for an irreplaceable friend.

… for The London Column. © David Secombe 2012.

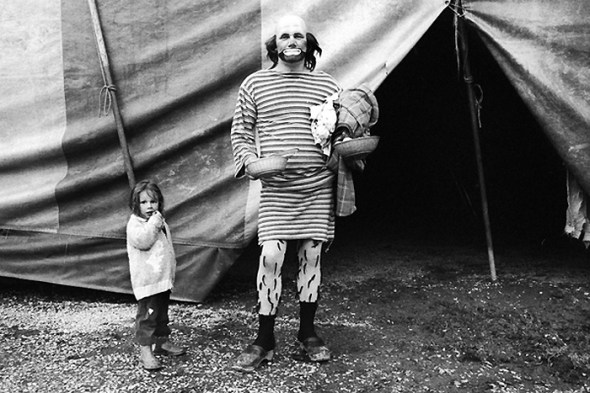

Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, text: Katy Evans-Bush. (3/4)

Posted: May 10, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Entertainment, London Types | Tags: Harlequin, hot codlins, Joseph Grimaldi, Pantaloon, Pantomime, Pierrot, Shakespeare's London 1 CommentSir Robert Fosset’s Circus. © Tim Marshall 1984

Katy Evans-Bush writes:

‘This fellow is wise enough to play the fool;

And to do that well craves a kind of wit:

He must observe their mood on whom he jests,

The quality of persons, and the time,

And, like the haggard, cheque at every feather

That comes before his eye. This is a practise

As full of labour as a wise man’s art

For folly that he wisely shows is fit;

But wise men, folly-fall’n, quite taint their wit.’

London Town is in a Shakespeare frenzy, as we approach th’Olympic Games: at this moment when bread itself is the issue, as well as the games themselves we have a military circus, with daily helicopters already circling, rooftop-mounted missiles on promise, and warships planning to swan along the Thames; as well as the bicentenary of one quintessentially London writer (and who knows that Dickens edited the memoirs of the great Grimaldi?) we have a months-long festival, with worldwide contributions, of the most London writer who ever lived: Shakespeare.

Consider the players of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men: hardworking, jobbing actors prepared to dress as women, as kings and queens and harlots and slaves and witches and knaves. As the prince, as the chorus, as the fool. For an audience who were prepared to suspend disbelief, to enter into the mystery and believe the magic. And in the early days of course they’d perform anywhere, innyards and palaces – the first theatres were open to the sky, and were big events. Almost Big Tops.

London isn’t where the theatre was first born, but it is where, in a great golden age not so far removed (really) from our own, which defined both its era and its city, a theatrical tradition was born that has spawned several others in its wake. One of those was the Fool, who could say things no one else dared – who could do things no one else dared – who was recognisable because he wore things nobody else dared, and whose folly hid a – or THE – truth, whether it was seen by the king he usually served (in the play) or only by the audience. Even the penny-a-place crowd in the pit could see his truth.

He was the transgressive twin – as Comedy is of Tragedy – of the chorus, of the announcer of – say – Romeo and Juliet‘s Prologue. He summed up the play, he explained it, he finished it, he was the relief within it and became the entertainment after it.

He disappeared, and came back in whiteface. He grew up in Clare Market (now under Aldwych), he played in Drury Lane, he played in music halls. He gave his name to the others: Joey. He consorted with trapeze artists and mimes, and when he lost his tragic ‘Shakespeherian’ context he learned to encompass his own tragedy.

He brought out his dresses again and was the Dame. He’s Pantaloon, and Pantomime, and Panto. He’s Pierrot, he’s the Kid, he’s Harlequin. Look out, he’s behind you.

He learned to use his body. He’s a cousin of Houdini. He gave us ‘slap’ for make-up and ‘slapstick’ for the kind of knockabout that makes your make-up come off. He grew out of the Old Kent Road, he foraged in Kennington, he was the Great Dictator, he played with his food, he shambled with a child, he wore old shoes.

He sits on straw so we don’t have to, and has elephants for company.

A little old woman

her living she got

by selling hot codlins,

hot, hot, hot.

And this little woman,

who codlins sold,

tho’ her codlins were hot,

she felt herself cold.

So to keep warm,

she thought it no sin,

to fetch for herself

a quartern of ……..

‘Oh, for SHAME!’

London made him. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you –

… for The London Column. © Katy Evans-Bush 2012.

Street traders. Photo David Secombe, text Susan Grindley. (3/3)

Posted: March 30, 2012 Filed under: Food, London Types, Markets, Street Portraits | Tags: Bobby Redrupp, Chapel Market, fruit and veg, Islington, London markets, Susan Grindley Comments Off on Street traders. Photo David Secombe, text Susan Grindley. (3/3)Bobby Redrupp and customer, Chapel Market, 1990. © David Secombe.

Leakage in Chapel Market, N1

She’s hanging on. I go to lunch.

An old man with a dewdrop on his nose

shuffles towards the market, inching round

a rotting mango and the discarded cartons

propped against the shop that takes my eye

with its display of candyfloss-pink chairs.

A boy reads from a placard to his friend

that Superman has lost his fight for life.

It’s only the cold wind that fills my eyes

and cyclamen in a new shade of purple.

© Susan Grindley.