Nights at the Opera. Photo & text: David Secombe. (5/5)

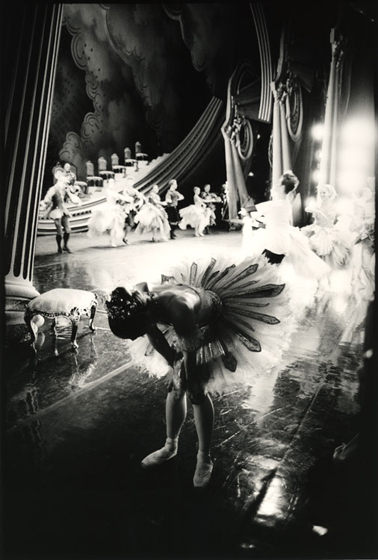

Posted: August 5, 2011 Filed under: Artistic London, Performers, Theatrical London | Tags: curtain call, Macmillan's Romeo and Juliet, Royal Ballet, Viviana Durante Comments Off on Nights at the Opera. Photo & text: David Secombe. (5/5)Viviana Durante taking her curtain call. Photo © David Secombe 1994.

To a Dancer by Arthur Symons:

Intoxicatingly,

Her eyes across the footlights gleam,

(The wine of love, the wine of dream)

Her eyes that gleam for me!

The eyes of all that see

Draw to her glances stealing fire

From her desire that leaps to my desire

Her eyes that gleam for me!

(There are two more verses of this awful poem, but I think we’ve heard enough.)

Viviana Durante is seen here taking a final bow at the end of Kenneth MacMillan’s acclaimed staging of Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet. This was the last concert of the season, a hot June night, and dance fans in the gods indulged in the agreeably cheesey custom of throwing flowers on to the stage as the principals took their calls. Ms Durante appears to be looking into the lens in this picture – this is likely, as the next frame shows her getting a fit of giggles as she looks at someone standing on my right. So you get it both ways: a poised ballerina straight from Symons’ coy imaginings, who sends up the entire form with a lethally witty gesture. Only someone seriously good can get away with that.

The London Column takes its own break for a week or so; material will be amassing in the mean time, so join us again later in the month.

David Secombe

Nights at the Opera. Photo & text: David Secombe (4/5)

Posted: August 4, 2011 Filed under: Theatrical London | Tags: Darcey Bussell, Royal Ballet, Tchaikovsky's Sleeping Beauty Comments Off on Nights at the Opera. Photo & text: David Secombe (4/5)Darcey Bussell, Royal Ballet Company, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Dress rehearsal of Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty. Photo © David Secombe, 1994.

From London: a book of Aspects by Arthur Symons, 1912

The most magical glimpse I ever caught of a ballet was from the road in front, from the other side of the road, one night when two doors were suddenly thrown open as I was passing. In the moment’s interval before the doors closed again, I saw, in that odd, unexpected way, over the heads of the audience, far off in a sort of blue mist, the whole stage, its brilliant crowd drawn up in the last pose, just as the curtain was beginning to go down.

Ballet is one of those art forms – like poetry and jazz – which may be cheerfully disparaged in polite conversation. Such discussions offer opportunities for the uninterested to dress up their prejudices at the expense of a form which is seen as a minority interest, the province of the uncool or the far too radical. I confess I shared a similar ignorance, even hostility, to dance until I started photographing it. I had been looking forward to seeing opera in the raw and regarded the ballet as a rather irritating add-on to my obligations on the Royal Opera House project. You see something on television and arrogantly assume you know enough to hold an opinion. As it turned out, I found the ballet thrilling and opera a comparative let-down (as theatre, anyway); but the dance was a real discovery. The staggering physicality of dancers at their physical and artistic peak: the noise of the corps de ballet thudding onstage is a shock in itself. Standing off-stage, or just in the wings – as I was when I took the picture above – gives you a glimpse of what it costs to defy gravity; the strain of the job showing just outside the frame of the proscenium arch. I went from total skeptic to convinced enthusiast: a faintly humbling position for a sedentary, overweight photographer to assume.

Some doubts remain. The Royal Ballet’s version of Daphnis and Chloe was a disappointment. Ravel’s rapturous score concludes with one of the great orgiastic frenzies in all art, but the action on stage was something akin to Morris Dancing, with the fabulous Viviana Durante and company poncing about with over-sized handkerchiefs. Even Bernard Haitink’s conducting couldn’t compensate for the absurdity of that.

© David Secombe 2011

Nights at the Opera. Photo & text: David Secombe (3/5)

Posted: August 3, 2011 Filed under: London Music, Theatrical London | Tags: Gawain, Harrison Birtwistle, John Tomlinson Comments Off on Nights at the Opera. Photo & text: David Secombe (3/5)

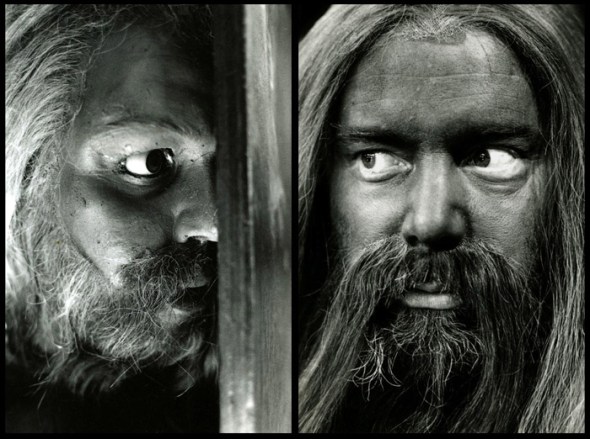

Sir John Tomlinson in make-up, right; model of Sir John’s head, left: Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. Photos © David Secombe, 1994.

Sir Harrison Birtwistle’s 1990s opera Gawain derives from the Middle English romance Sir Gawain and The Green Knight, in which the titular hero avenges the honour of King Arthur by decapitating the mysterious Green Knight who has appeared at court and insulted the King. This being a medieval romance, the Green Knight picks up his severed head and invites Gawain to a return match one year hence.

The Royal Opera House commissioned the opera from Birtwistle, with a libretto by David Harsent. The commission was an ideal match of subject and composer, given Birtwistle’s fondness for using mythic narratives as a foil for his austere, modernist style. In the photograph above right, the great Wagnerian bass John Tomlinson (now Sir John Tomlinson) sits in make-up, having just been transformed into the Green Knight. To facilitate his onstage decapitation, a model of Sir John’s head was made (above left, nestling in its box) commissioned from television’s Spitting Image puppet-making team.

The 1994 revival of Gawain at the Royal Opera House was booed by a group of musicians opposed to all post-romantic developments in classical music; they called themselves ‘The Hecklers’ and went to the opera for the purpose of abusing the work and its composer. Naturally, the publicity drew more attention to the opera and Birtwistle himself, as did the programming of his characteristically uncompromising saxophone concerto Panic at 1995’s Last Night of the Proms. Birtwistle’s music reminds this listener of the best 1960s Brutalist architecture: short on charm, but supremely confident in its structural integrity and expression of purpose. That said, my own attendance at the opera lasted about fifteen minutes, after which I went to the crush bar in search of a gin and tonic. D.S.

Nights at the Opera. Photo & text David Secombe (2/5)

Posted: August 2, 2011 Filed under: London Music, Theatrical London | Tags: Cherubin, Jane Mitchell, Massenet 3 Comments

Jane Mitchell, backstage, Royal Opera House, 1994. Photo © David Secombe.

Massenet’s Cherubin is a comic opera conceived as a sort of sequel to The Marriage of Figaro. It has received a few revivals in recent years, notably a splendid 1994 production at the Royal Opera House which featured Susan Graham, Angela Georghiou and some extremely arresting wigs. The photo above was taken on the first night of this production, and shows the soprano Jane Mitchell waiting in the wings for her final entry. In the backstage gloom, Jane’s marvellous profile was illuminated by just one, blue worklamp – and I had just enough time (about a minute) to set up my tripod and take a few frames before she left for the finale.

(You can hear Susan Graham and Angela Georghiou in this production here: a duet from the finale.)

I was working on a book project profiling a season of opera and ballet at the Royal Opera House, an offshoot of the famous BBC documentary series The House. The films painted a fascinating and not-entirely flattering portrait of life within the building, and several sackings and resignations ensued. As a stills photographer, I was less concerned with organisation’s internal politicking than I was with the sheer beauty of the working environment. However, complaints about the inadequacy of this environment and its antiquated facilities eventually led to the major redevelopment of the building, which was tied to a major re-landscaping of Covent Garden to monetize the scheme. The unfortunate consequence of this has been a further loss of character for the area: one entire Georgian terrace on the north side of Russell Street was demolished, creating more facilities for the ROH but also adding yet more chain outlets to a district choked by them.

(It may sound feeble, but I promised Jane a copy of this picture, a promise I never delivered; Jane, if you are reading this, drop me a line and I will make good on this. D.S.)