Underground, Overground. Text: Andrew Martin, photo: Tim Marshall. (2/5)

Posted: May 29, 2012 Filed under: Sartorial, Tall Tales, Transport | Tags: Andrew Martin, Bella Freud, Underground Overground, Valentine's Day Comments Off on Underground, Overground. Text: Andrew Martin, photo: Tim Marshall. (2/5)Piccadilly line. © Tim Marshall 1992.

Andrew Martin writes:

For Valentine’s Day, an editor once instructed me, ‘I want you to write about love on the Underground’, but I couldn’t dig up much. I read in Underground News that on 30 April 1986 at bank station a woman hit her eighty-year old husband with a handbag, which sent him tumbling down an escalator. Just before Christmas in 1989, an Underground labourer who had consumed ten pints of bitter had an unorthodox interaction with a cat on a Tube train. Then he fell into a stupor, and his first remark on being awakened by an appalled fellow passenger was, ‘What cat?’ He was later fined £500. For many years the dating agency Dateline placed posters throughout the Underground that showed a man and a woman crossing on adjoining escalators. ‘A hidden glance, a forgotten smile’ ran the copy. ‘Have you ever looked and wondered what might have been?’ That drove me mad, because if you’d forgotten the smile then you wouldn’t wonder what might have happened as a result of it. Even so, when the fashion designer Bella Freud (who launched one of her collections on a Tube train) said, ‘There’s a strange tension on the Tube, a moodiness, a sexiness’. I think she was right.

The text is from Underground, Overground: a passenger’s history of the Tube, published by Profile Books (also available here.) The photos are from Tim Marshall’s series When a Tube train stops.

Underground, Overground. Text: Andrew Martin, photo: Tim Marshall. (1/5)

Posted: May 28, 2012 Filed under: Transport | Tags: Andrew Martin, evening commute, the Tube, Underground Overground Comments Off on Underground, Overground. Text: Andrew Martin, photo: Tim Marshall. (1/5)Piccadilly line. © Tim Marshall 1991.

Andrew Martin writes:

In my boyhood, the system was not what it had been in the triumphalist inter-war heyday, and nor was it like the spruce, sparkling (if badly overcrowded), upgraded Underground of today. In the Seventies the system was run-down and demoralised. Road transport was the future; the Underground was being ‘managed for decline’, and the system was filthier even than the streets above. You were not to lean against the station walls, or that was your rally jacket ruined. In most of the stations about a quarter of the tiles would be broken. Sometimes the station name was meant to be spelled out by the tiles, and Londoners’ toleration of the position at, say, Covent Garden – rendered for years as something like ‘COV-TG-DEN’ – implied an impressive broad-mindedness on their part.

You could actually see the atmosphere in the stations: it was sooty, particulate. There is an Underground poster from the late Thirties by Austin Cooper that advertised something as un-mysterious as ‘Cheap Return Tickets’ but did so with an abstract image: a lonely searchlight trying to penetrate a jaundiced miasma. That was the Underground of my boyhood: a marvel of engineering but also a dream space, in which people of all classes and races would float past you, with the strange buoyancy of a passing carriage. In the case of people in your own carriage (or ‘car’, since the Underground is riddled with American railway terminology), you could look at them directly, or you could look at their reflections in the windows, and they would be sunk in their own dreams; all this under electric light, so that it always seemed – as it always still seems – to be evening on the Tube, which is my favourite time of day.

The text is from Underground, Overground: a passenger’s history of the Tube, published by Profile Books (also available here). The photos are from Tim Marshall’s series When a Tube train stops.

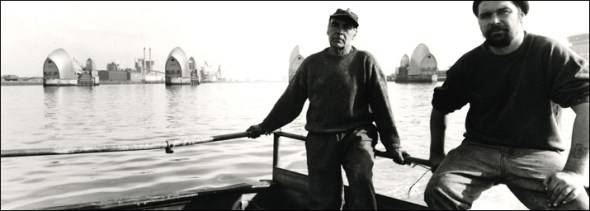

Flotsam and jetsam. Photo & text David Secombe. (2/5)

Posted: April 17, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Artistic London, The Thames, Transport | Tags: Britart, commercial Thames, corporate London, Damien Hirst, Spot paintings, Tate Boat, Tate Britain, Tate Modern, tate to tate 1 CommentThe Thames, looking east from Hungerford Bridge, 2010. Photo © David Secombe.

From Tate Online : 1 May 2003:

From 23 May Tate to Tate, a new boat service on the river Thames, will be available for gallery lovers. The service, which runs every forty minutes during gallery opening hours between Tate Modern and Tate Britain, will be launched on 22 May by The Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone. The boat also stops at the London Eye.

The Tate to Tate boat service, operated by Thames Clippers, is a state-of-the art 220 seat catamaran with specially commissioned exterior and interior designs by leading artist Damien Hirst. The boat is sponsored by St James Homes, a property developer.

David Secombe writes:

Now that Damien Hirst is the richest artist in the world (proof if any were needed of the global success of that strange London-based phenomenon known as ‘BritArt’), it seems entirely fitting that ‘the fastest’ commercial vessel on the Thames, ferrying passengers to and from the world’s most popular – some might say populist – art gallery, bears one of his patented designs. The Tate boat is decorated with Hirst’s bright, multi-coloured dots, and travels between those twin bastions of culture, Tate Modern and Tate Britain – the former fashioned from a derelict power station, the latter built on the site of a penitentiary.

For good or ill, Hirst seems to be the artist who best embodies his time; one can’t imagine a Bacon Barge or a Rothko Raft, whereas our Damien’s spotty pleasure cruiser – made possible by a property consortium – seems completely, depressingly, apt.

(The London Column has not yet felt the siren call of the current Hirst exhibition at the Tate, but you can read a response to the Sotheby’s extravaganza of 2008 on Baroque in Hackney. For another view of Hirst and his influences, see: http://www.stuckism.com/Hirst/StoleArt.html.)