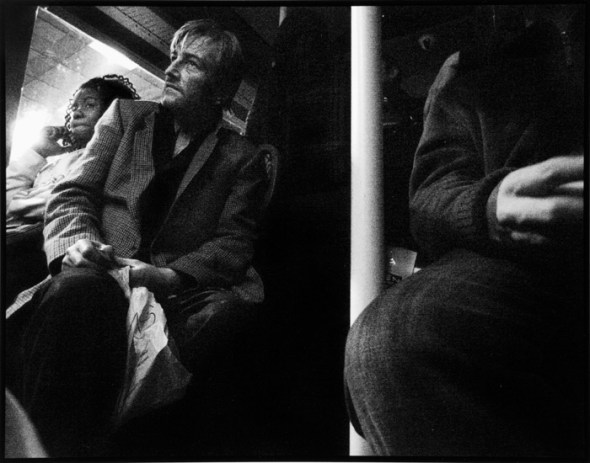

38 Special. Photo & text: Tim Marshall (5/5)

Posted: July 15, 2011 Filed under: Transport | Tags: number 38, Tim Marshall, Walker Evans Comments Off on 38 Special. Photo & text: Tim Marshall (5/5)Angel. Photo © Tim Marshall.

Tim Marshall:

I started the ’38 Special’ bus project largely because the bus was always so overcrowded that rarely could you get a seat to read the paper. So, in order to fill the time, I began to take photographs during my journey to and from college. The whole of life’s rich tapestry unfurls on a bus and I soon extended the brief to observe the small dramas that occurred outside the bus as well. Although the real action often happens when I pass college and head towards China town and Piccadilly Circus, the main challenge had been documenting the journey from Essex Road to Central Saint Martin’s.

David Secombe:

Between 1938 and 1941, the great Walker Evans took his (suitably disguised) camera on the New York subway and photographed unwitting passengers. The photo are sweet and revealing but don’t have that unflinching, forensic power that we associate with Evans at his best: the man who photographed the faces and homes of poor, Depression-era farmers with such eloquence and grace. Tim has cited Walker Evans’ 1930s photos of the New York subway as an influence, but unlike Evans, Tim Marshall was not trawling the public transit systems for material, he was keeping a visual diary as he travelled to work. When he photographs bored commuters stuck on a bus stranded by traffic, he is one of them. These days, a photographer taking his camera onto public transport risks exposure, ridicule, violence and possibly arrest. I don’t know what subterfuges Tim used in order to conjure up the images that make up his 38 Special project, but as the image reproduced above shows, it was worth it. We will run more of them later in the year.

38 Special. Photo Tim Marshall, text Travis Elborough (4/5)

Posted: July 14, 2011 Filed under: Transport | Tags: No. 38, Timothy Hadrian Marshall, Travis Elborough, Tysoe Street Comments Off on 38 Special. Photo Tim Marshall, text Travis Elborough (4/5)On board a 38, Tysoe Street, Islington. 2005. Photo © Tim Marshall.

From The Bus We Loved; London’s affair with the Routemaster* by Travis Elborough:

When I started writing this book I was living in Tufnell Park, in a flat bang opposite the tube. Hulking, over-sized overfed double-decker buses on route 134 to Archway drove past our kitchen window every hour of the day, creating a thrum and a hiss that was impossible to ignore. Around the corner, fractionally our of view and completely out of earshot, the 390 Routemasters ploughed back and forth to King’s Cross, in their own quietly efficient and self-effacing way. Most mornings I used to catch one down to the British library near St. Pancras, savouring the pleasures of the ride, before spending the day browsing self-published pamphlets on the Greenline service of the 1960s.

On my walk to the bus stop I’d usually see an elderly derelict, his hands always encased in oversized industrial rubber gloves, clinging on to the railings near the Spaghetti House restaurant on the corner of Fortress Road. Ahab on the slipstreams of the A1, his mornings were devoted to staring at the flows of traffic that passed before him. Usually a sage-like observer, indifferent to the sirens, beeping horns and screeching tyres, he would intermittently be roused into rage by particular vehicles. Refuse lorries caused him no end of dismay.

Later in the year I moved to Stoke Newington but a few weeks afterwards I had to return to the old flat to pick up some post. Coming out of the tube on a grey autumn afternoon, I found old rubber gloves was still there; this time howling like a banshee at a brand new double-decker on route 390. He sounded as if he was in pain, but then he’d always sounded that way. It’s easy, perhaps, to read too much into these things.

© Travis Elborough 2011

* Published by Granta.

38 Special. Photo: Tim Marshall, text Susan Grindley (3/5)

Posted: July 13, 2011 Filed under: Literary London, Transport 1 CommentExmouth Market, 2002. © Tim Marshall.

The Man in the Violet Polo Shirt by Susan Grindley

Like a mime-artist performing brain-surgery,

the man in the violet polo-shirt –

seeing that neither driver would back down and back up,

and after a final, ‘Why should I?’ from each –

coaxed the Vauxhall between the 277 and the steel cage

enclosing the road works.

At spitting-range there was another bout of shouting

but, from the bus, the street and the cars,

backed-up, hooting, in Frampton Park Road

and Well Street, we could see it was a win-win situation,

so when the man in the violet polo-shirt came back onto the bus,

some of us clapped.

[This poem first appeared in Rising magazine.]

38 Special. Photo: Tim Marshall, text Travis Elborough (2/5)

Posted: July 12, 2011 Filed under: Transport | Tags: Routemaster, Tim Marshall, Travis Elborough Comments Off on 38 Special. Photo: Tim Marshall, text Travis Elborough (2/5)On a number 38 ‘Bendy’, Islington, 2006. Photo © Tim Marshall.

From The Bus We Loved; London’s affair with the Routemaster* by Travis Elborough:

The Routemaster was made to measure, Savile Row tailored for the city, ‘an attractive piece of street furniture’ specifically built for London. It exemplified the highest ideals of a public-spirited passenger transport service – physical evidence that London and ordinary Londoners should have the very best. ‘A handsome city deserves a handsome transport’ as All That Mighty Heart, the London Transport film, proclaimed in 1962. We loved it, not because it was old and quirky, but because it was bloody good. Well made. Importantly, it was greeted as an equal. It respected our custom. It was comfortable. Convenient. Efficient. We were free to get on and off, within reason, when we wanted to. ‘Passengers’ an old London transport motto maintained, ‘are our business not an interruption to our service.’ And on a Routemaster you could believe in that too.

Of course it grew out of and was born into another world. The society it was created to serve was more, or more visibly, stratified. It was a world with a certain intolerance of difference; you might see in its straight rows of seats a reflection of those times. A bus built for a city known for forming orderly queues rather than for wild alcoholic sprees; for a city of parsimonious coupon-snippers rather than designer-label consumers. It’s a bus that can exclude (the disabled, the pushchair), I concede. I prefer, however, to see a more egalitarian spirit at work. It was designed for (nearly) everyone, and everyone aboard is equal. By its careful, skilful design, it was intended in some small was to elevate an everyday experience.

By contrast, the metaphors many modern buses offer are slightly depressing. Their designs indicate troubled minds; seats on different levels, seats back to front, lurid playpen fabrics and colour schemes, straps at unusable heights, lava-lamp globules of extruded plastic at every turn and a soundtrack of bleeps and ticks, the Bendy’s have all the aesthetics of the inside of a Hoover attachment. New double deckers are huge, boxy, noisy and unwieldy. They look deformed, bulked out like Action Man after Hasbro pumped him full of steroids and turned him into some kind of inhuman gym-bunny cyberpunk in the 1990s. The average speed of a London bus continues to hover around 11 mph, and yet the engines on these vehicles seem tuned to accelerate with a speed and abruptness previously reserved for propelling dogs into space.

© Travis Elborough 2011

* Published by Granta Books.