Don’t Put Your Daughter On The Stage

Posted: July 19, 2013 Filed under: Theatrical London | Tags: Annie, Apollo Victoria, Don't Put your daughter on the stage, Noel Coward 1 CommentAudition line; open casting call for Annie, Apollo Theatre, Victoria. Photo © David Secombe, 1980.

From Noel Coward On The Air, 1947:

Some years ago when I was returning from the Far East on a very large ship, I was pursued around the decks every day by a very large lady. She showed me some photographs of her daughter, a repellent-looking girl, and seemed convinced that she was destined for a great stage career. Finally, in sheer self-preservation, I locked myself in my cabin and wrote this song:

Don’t Put Your Daughter On The Stage, Mrs. Worthington.

Don’t put your daughter on the stage, Mrs. Worthington

Don’t put your daughter on the stage

The profession is overcrowded

The struggle’s pretty tough

And admitting the fact she’s burning to act

That isn’t quite enough

She’s a nice girl and though her teeth are fairly good

She’s not the type I ever would be eager to engage I repeat,

Mrs. Worthington, sweet Mrs. Worthington

Don’t put your daughter on the stage

[ … etc. The rest of the lyrics may be found here.]

Arthur Machen’s Hill of Dreams.

Posted: July 4, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Bohemian London, Fictional London, Literary London | Tags: Arthur Machen, Battersea, Hill of Dreams, pipe smoker Comments Off on Arthur Machen’s Hill of Dreams.Tennyson Street, Battersea. Photo © David Secombe 1982.

From Hill of Dreams, Arthur Machen, 1907:

It was not till the winter was well advanced that he began at all to explore the region in which he lived. Soon after his arrival in the grey street he had taken one or two vague walks, hardly noticing where he went or what he saw; but for all the summer he had shut himself in his room, beholding nothing but the form and colour of words. [. . .]

Now, however, when the new year was beginning its dull days, he began to diverge occasionally to right and left, sometimes eating his luncheon in odd corners, in the bulging parlours of eighteenth-century taverns, that still fronted the surging sea of modern streets, or perhaps in brand new “publics” on the broken borders of the brickfields, smelling of the clay from which they had swollen. He found waste by-places behind railway embankments where he could smoke his pipe sheltered from the wind; sometimes there was a wooden fence by an old pear-orchard where he sat and gazed at the wet desolation of the market-gardens, munching a few currant biscuits by way of dinner. As he went farther afield a sense of immensity slowly grew upon him; it was as if, from the little island of his room, that one friendly place, he pushed out into the grey unknown, into a city that for him was uninhabited as the desert.

At 11.30 a.m. (UK) today, Thursday 4 July, Radio 4 is broadcasting a documentary about Arthur Machen and his ‘disturbing’ visions of a world beyond our own.

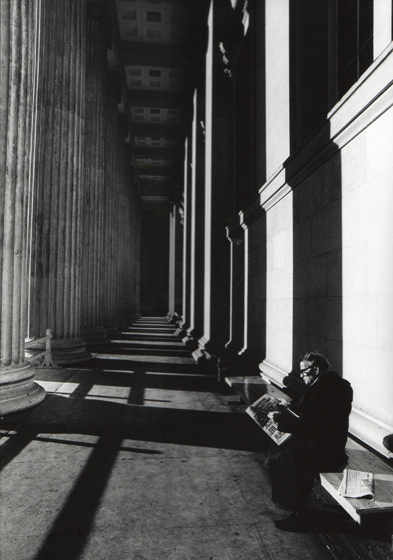

The British Museum Reading Room

Posted: July 1, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Literary London | Tags: British Museum Reading Room, Louis MacNeice Comments Off on The British Museum Reading RoomPhoto © David Secombe 1988.

The British Museum Reading Room by Louis MacNeice, 1939:

Under the hive-like dome the stooping haunted readers

Go up and down the alleys, tap the cells of knowledge –

Honey and wax, the accumulation of years …

Some on commission, some for the love of learning,

Some because they have nothing better to do

Or because they hope these walls of books will deaden

The drumming of the demon in their ears.

Cranks, hacks, poverty-stricken scholars,

In prince-nez, period hats or romantic beards

And cherishing their hobby or their doom,

Some are too much alive and some are asleep

Hanging like bats in a world of inverted values,

Folded up in themselves in a world which is safe and silent:

This is the British Museum Reading Room.

Out on the steps in the sun the pigeons are courting,

Puffing their ruffs and sweeping their tails or taking

A sun-bath at their ease

And under the totem poles – the ancient terror –

Between the enormous fluted ionic columns

There seeps from heavily jowled or hawk-like foreign faces

The guttural sorrow of the refugees.

[The Reading Room is now merely an exhibit, the centre piece of Foster and Partners’ Great Court. The scholars now have to go up the Euston Road to the British Library.]

Another photo of Tim Andrews.

Posted: June 13, 2013 Filed under: Bohemian London, Gardens | Tags: Alex Boyd, Guardian Gallery, Harry Borden, Over The Hill, Parkinson's disease, The Culture SHow, Tim Andrews 1 Comment Tim Andrews, Surrey. © David Secombe 2010.

Tim Andrews, Surrey. © David Secombe 2010.

Tim Andrews, Over The Hill blog, 5 February 2012:

I love my body at the moment…..it’s not that I think it looks good (according to whatever criteria one uses to define a good looking body)……..it’s just that it is all I’ve got but this bloody disease is chipping away at it and I am hanging on to what physicality I still have…….and maybe that is why I do so much photography and filming in the nude………..well, partly why………..I do feel that clothes make statements which is fine but a body is just you, unadorned…….and it says so much more…….no I can’t tell you what more it says for I am a bear of little brain………..

In the luminous glass box of the Guardian Gallery, situated in the foyer of the newspaper’s offices in King’s Cross, I am surrounded by images of one man. This man is not a cultural figure or head of state; he is an ex-solicitor from Surrey who took early retirement following a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. The occasion is the private view of Over The Hill: A Photographic Journey, subtitled ‘One man’s confrontation with his own mortality’, an exhibition (sponsored by Parkinson’s UK) featuring the work of 30 out of the 240-odd photographers who have photographed Tim Andrews since 2008. I was invited because the image above was selected – by The Guardian – as one of the exhibits.

Over The Hill is an unusual undertaking inasmuch as it is a form of extended self-portraiture by someone who is not an artist. Tim Andrews expresses himself by making himself available to photographers to photograph. One tries to think of precedents but the only one I can offer is that of a Renaissance prince, a Medici or similar, commissioning many portraits in order to contemplate his corporeal being. The difference between Tim Andrews and your average Medici is that Tim likes to be portrayed in the buff, and foregrounds this preference in discussions with the photographers. As indicated by the quote above, Tim equates nakedness with truthfulness, but this has always been contentious and is even more so when spoken by a subject keen to get his kit off for the camera.

At any rate, a wide range of photographers have been happy to photograph Tim and many have taken him up on his offer to disrobe; yet whilst their sympathy towards their subject is palpable, there are more than a few images wherein he appears as no more than a conceptual prop. The ex-solicitor is asked to represent weighty themes: the ‘identity of the body’, the nature of disability, and, yes, the confrontation with mortality. We see him as a wood nymph, as a saint, as Shiva, etc. Forensic psychological portraiture is at a premium (notable exceptions include Harry Borden and Alex Boyd) and there is also a note of competition, as big names and aspiring art photographers vie with each other to create the most eye-catching image of an increasingly desirable ‘scalp’.

What do we know about Tim Andrews? I can tell you that he is a very nice man who didn’t like being a solicitor – he really wanted to be an actor – who is one of the 127,000 people in the UK who suffer from Parkinson’s. I don’t know if Over The Hill tells us anything we didn’t already know about the condition – a difficult disease to depict in a still image – but it reveals something about Tim Andrews, and quite a lot about the nature of modern fame. His journey from frustrated provincial solicitor to art world pin-up has all the key ingredients of an Arts & Lifestyle feature: mid-life crisis, sudden illness, confessional memoir, nudity, and the glamour of association with celebrity (the distant connection between Tim Andrews and the famous subjects of the better-known photographers involved). I don’t doubt that Tim Andrews is anything less than utterly sincere, but it is hard to overlook the compulsive exhibitionism – masochism, even – of the project. And despite the accomplishment of much of the work in it, Over The Hill has the feeling of a scrapbook: Tim gives the pictures titles and adds a whimsical, inward-looking commentary that tends to smother them. No image is allowed to speak on its own terms. There is a lot going on here, but it needs someone other than the subject of the photos to unpack it.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the project is the oblique insight it affords us into the mystery of portraiture. Some of the most memorable faces on the planet are people famous only for their appearance in a great image: August Sander’s farmers, Paul Strand’s blind woman, Brassai’s drinker, Don McCullin’s shell-shocked marine, Diane Arbus’s boy in curlers, Eve Arnold’s Chinese lady, etc. We know nothing about the histories of these people but the images are indelible. On the other hand, we have the Great photographed by the Great; so here’s Francis Bacon by Bill Brandt, Truman Capote by Irving Penn, Ezra Pound by Richard Avedon, Camus by Cartier-Bresson – and, for that matter, Graham Greene by Dmitri Kasterine. Such portraits have myth-making capacity. By contrast, the subject of Over The Hill is both anonymous and celebrated; an ordinary man made extraordinary by the elaborate attention paid to him. It’s a cute story but, inevitably, the law of diminishing returns applies. The endless repetition of Tim’s body, with and without clothes, becomes a hall of mirrors: the more distorted the reflection, the less we apprehend the person in the frame. What the viewer sees is Tim looking at the photographers looking at him looking at them.

But none of these caveats really matter. It is clear that being seen is Tim’s overriding concern, the images themselves are of secondary importance. His story is redolent of an Edwardian bohemian fantasy, and if he’d lived in an earlier era he might have inspired a novel by Arnold Bennett or Somerset Maugham. He is The Man Who Lived Again; and he has used his failing body to proclaim his existence.

Over The Hill runs at the Guardian Gallery, King’s Place, London N1, until 21st June. A selection from the project is also on show at the Farley Farm House gallery, Sussex, during June and July.