Rotherhithe. Photo & text Geoff Howard (3/5)

Posted: September 5, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Parks | Tags: Geoff Howard, Rotherhithe, Southwark Park, Surrey Docks, would Cartier-Bresson ever use flash? Comments Off on Rotherhithe. Photo & text Geoff Howard (3/5)Carnival, Southwark Park, London, July 1974. © Geoff Howard.

Geoff Howard:

I photographed the people and places that caught my attention, shooting from an interest in, and a curiosity about, what was there and what was happening, happy to be working without the restrictions which often accompany commissioned projects. People have asked why I shot with flash – in those days, most photographers would only use available light – shades of Cartier-Bresson – but in the disco pubs, it was really dark – and I wanted to see, to show more clearly, what it was like, what was happening; less atmosphere, but more information. I stopped photographing there so intensively when I felt I had done the things which demanded to be photographed, and I didn’t want to make the same pictures over again. Then the whole area, the whole character of the area, changed – with redevelopment, new building, the yuppyfication of docklands; there were lots of photographers documenting the new docklands, and if I had continued, it would have been a different story, so it seemed like a natural end, a natural place to stop. I have been back, a few times – I was there last year, to try and check some locations when I started putting this book together; it was interesting, frustrating, indeed perplexing trying to identify places I used to know well, and now so changed.

[Rotherhithe Photographs was published in 2008, although images from the project had previously appeared in the legendary Creative Camera magazine in 1975, and a selection of pictures was also exhibited at London’s Whitechapel Art Gallery in 1978. Seen from the vantage point of 2012, Geoff’s photos capture the half-forgotten ‘interzone’ between the dock closures and Thatcherite redevelopment and demonstrate, yet again, that there is nothing quite as remote as the recent past. D.S.]

Rotherhithe Photographs: 1971-1980 by Geoff Howard is available direct from the photographer at £25.

Hockley Hole, AKA Central Saint Martins. Photo & text: David Secombe.

Posted: May 16, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Artistic London, Bohemian London, Public Art, Vanishings | Tags: Back Hill, Central Saint Martins, Common People, Hockley in the Hole, John Driscoll, Johno's Darkroom 2 CommentsBack Hill, 2010. © David Secombe.

From The Fascination of London: Holborn and Bloomsbury, edited by Sir Walter Besant 1903:

The lower part of Saffron Hill was known at first as Field Lane, and is described by Strype as “narrow and mean, full of Butchers and Tripe Dressers, because the Ditch runs at the back of their Slaughter houses, and carries away the filth.” Just here, where Back Hill and Ray Street meet, was Hockley Hole, a famous place of entertainment for bull and bear baiting, and other cruel sports that delighted the brutal taste of the eighteenth century. One of the proprietors, named Christopher Preston, fell into his own bear-pit, and was devoured, a form of sport that doubtless did not appeal to him. Hockley in the Hole is referred to by Ben Jonson, Steele, Fielding, and others. It was abolished soon after 1728. All this district is strongly associated with the stories of Dickens. In later times Italian organ-grinders and ice-cream vendors had a special predilection for the place, and did not add to its reputation.

David Secombe writes:

One might add that in the 20th century, the area described above became associated with the photographic profession: at one time Clerkenwell was said to have more darkrooms and studios per square foot than anywhere else in the world. As a coda to yesterday’s post remembering the great Johno Driscoll, here’s a picture of ‘found art’ posted to the wall of John’s old premises, Holborn Studios, which is now a campus for Central Saint Martins art college. The building is situated within ‘the Hole’ – although the site of the bear-pit itself is now occupied by the pub opposite, The Coach and Horses. (Allegedly, the pub once afforded access to the Fleet river from its cellars, providing 18th Century fugitives with an escape route to the Thames.) Somehow, it seems right and proper that one of the most disreputable spots in 16th and 17th Century London should have gone on to be associated with photography, fashion, and art: the favoured trades of chancers, ne’er-do-wells and diamond geezers.

… for The London Column. See also: Little Jimmy, King of Clerkenwell.

Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, texts: Joanna Blachnio & Tim Marshall (4/4)

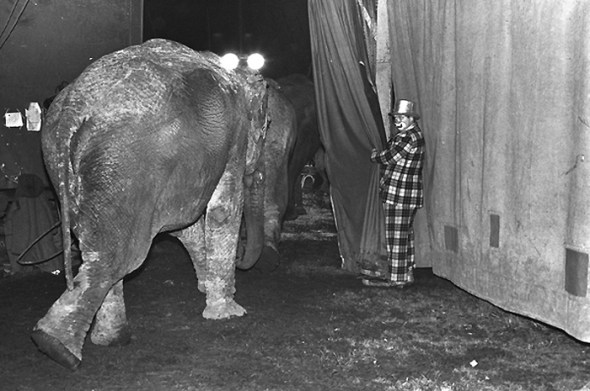

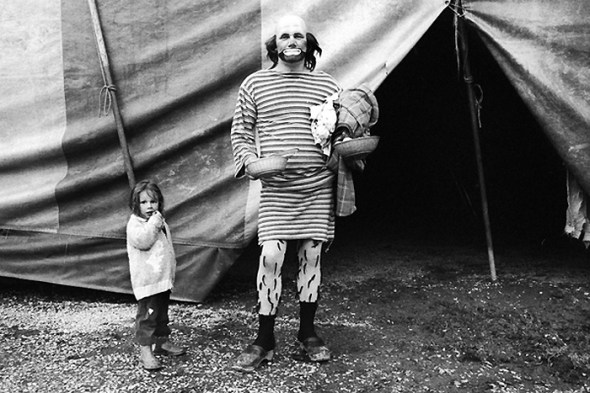

Posted: May 11, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Performers, Wildlife | Tags: Chunee, circus elephant, Clapham Common, clowns, Exeter Change, Joanna Blachnio, Julius Caesar, mad elephant, Royal Menagerie, Sir Robert Fossett's Circus, Tim Marshall Comments Off on Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, texts: Joanna Blachnio & Tim Marshall (4/4)Sir Robert Fosset’s Circus. © Tim Marshall 1984.

Joanna Blachnio writes:

Elephants in London have a long history. Tradition has it that Julius Caesar used a war elephant during his invasion of Britannia; he and his forces pitched camp not far from modern-day Bromley, so this un-named animal might be said to be the first pachyderm to impress suburban Londoners. In the 13th century, there was an African elephant amongst the Royal Menagerie which resided at the Tower of London – a gift from Louis IX of France. Plus, there is the elephant at the Elephant and Castle – although that area got its name from an 18th century coaching inn that stood in the vicinity.

One of the most poignant stories in the bestiary of London was that of Chunee, the mad elephant of Covent Garden. This sad creature arrived in Britain from India in 1809 as a theatrical and, later circus, animal, becoming one of the city’s attractions for almost two decades: even Lord Byron took note of his dexterity and good manners. He spent his dotage in the fabled menagerie at Exeter Change in The Strand, increasingly tormented by loneliness (there was no mate to help him while the time away) and a bad tusk. In February 1826, during his weekly parade down the Strand, Chunee rebelled against his captivity and went berserk, trampling one of his keepers in his rage. His temper did not subside and a death sentence was passed. The convict, however, clung on to life with the strength proportional to his body mass – almost seven tons. When they tried poisoning his food, Chunee was having none of that, and would not touch it. A troop of soldiers were sent for, yet even the fusillade from their muskets failed to kill the elephant, whose moans allegedly caused more distress than the sound of gunfire. Finally, one of his keepers ended his agony with a sword.

The elephants in Tim Marshall’s photograph are remote from the romance and pathos surrounding the death of their famous London ancestor. An impassive clown holding the curtain aside for their entrance, they take the stage with the weary docility of ageing pros. Their thick skin seems whitewashed in the glare of the stage lights. The last elephant to take to the ring can probably only sense what we are able to see: how much space there is in his wake.

Tim Marshall writes:

These photographs where taken in Easter 1984. At that time I was a student at Central St Martins School of Art making a life changing decision to stop illustrating with a pen and to start doing it with a camera.

I spent about four days photographing Sir Robert Fosset’s Circus. I remember going to Clapham Common at 8.00 in the morning, and before the circus site was in view hearing tigers roaring and elephants trumpeting, which was very surreal in central London. I photographed the tent being put up and only realized later that, everybody worked as a team and very hard. The tiger trainer helped put up the tent, starlets of the trapeze would, after finishing their acts, sell candy floss. Clowns empted bins. The clown Nelo, was not actually that funny and quite sad. Children would laugh at him rather than with him. He was a clown whose personal life seemed to be in complete disarray. But he wanted to be loved and make people happy.

After the show, I remember that certain pubs had a ‘no travellers‘ policy, so the people from the circus were refused entrance; and in the pubs they did manage to get into, they were only allowed in to the public bar rather than the lounge.

… for The London Column. © Joanna Blachnio, © Tim Marshall, 2012.

Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, text: Katy Evans-Bush. (3/4)

Posted: May 10, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Entertainment, London Types | Tags: Harlequin, hot codlins, Joseph Grimaldi, Pantaloon, Pantomime, Pierrot, Shakespeare's London 1 CommentSir Robert Fosset’s Circus. © Tim Marshall 1984

Katy Evans-Bush writes:

‘This fellow is wise enough to play the fool;

And to do that well craves a kind of wit:

He must observe their mood on whom he jests,

The quality of persons, and the time,

And, like the haggard, cheque at every feather

That comes before his eye. This is a practise

As full of labour as a wise man’s art

For folly that he wisely shows is fit;

But wise men, folly-fall’n, quite taint their wit.’

London Town is in a Shakespeare frenzy, as we approach th’Olympic Games: at this moment when bread itself is the issue, as well as the games themselves we have a military circus, with daily helicopters already circling, rooftop-mounted missiles on promise, and warships planning to swan along the Thames; as well as the bicentenary of one quintessentially London writer (and who knows that Dickens edited the memoirs of the great Grimaldi?) we have a months-long festival, with worldwide contributions, of the most London writer who ever lived: Shakespeare.

Consider the players of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men: hardworking, jobbing actors prepared to dress as women, as kings and queens and harlots and slaves and witches and knaves. As the prince, as the chorus, as the fool. For an audience who were prepared to suspend disbelief, to enter into the mystery and believe the magic. And in the early days of course they’d perform anywhere, innyards and palaces – the first theatres were open to the sky, and were big events. Almost Big Tops.

London isn’t where the theatre was first born, but it is where, in a great golden age not so far removed (really) from our own, which defined both its era and its city, a theatrical tradition was born that has spawned several others in its wake. One of those was the Fool, who could say things no one else dared – who could do things no one else dared – who was recognisable because he wore things nobody else dared, and whose folly hid a – or THE – truth, whether it was seen by the king he usually served (in the play) or only by the audience. Even the penny-a-place crowd in the pit could see his truth.

He was the transgressive twin – as Comedy is of Tragedy – of the chorus, of the announcer of – say – Romeo and Juliet‘s Prologue. He summed up the play, he explained it, he finished it, he was the relief within it and became the entertainment after it.

He disappeared, and came back in whiteface. He grew up in Clare Market (now under Aldwych), he played in Drury Lane, he played in music halls. He gave his name to the others: Joey. He consorted with trapeze artists and mimes, and when he lost his tragic ‘Shakespeherian’ context he learned to encompass his own tragedy.

He brought out his dresses again and was the Dame. He’s Pantaloon, and Pantomime, and Panto. He’s Pierrot, he’s the Kid, he’s Harlequin. Look out, he’s behind you.

He learned to use his body. He’s a cousin of Houdini. He gave us ‘slap’ for make-up and ‘slapstick’ for the kind of knockabout that makes your make-up come off. He grew out of the Old Kent Road, he foraged in Kennington, he was the Great Dictator, he played with his food, he shambled with a child, he wore old shoes.

He sits on straw so we don’t have to, and has elephants for company.

A little old woman

her living she got

by selling hot codlins,

hot, hot, hot.

And this little woman,

who codlins sold,

tho’ her codlins were hot,

she felt herself cold.

So to keep warm,

she thought it no sin,

to fetch for herself

a quartern of ……..

‘Oh, for SHAME!’

London made him. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you –

… for The London Column. © Katy Evans-Bush 2012.