Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, texts: Joanna Blachnio & Tim Marshall (4/4)

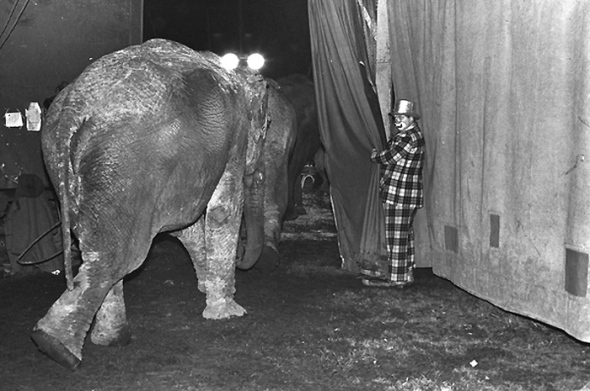

Posted: May 11, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Performers, Wildlife | Tags: Chunee, circus elephant, Clapham Common, clowns, Exeter Change, Joanna Blachnio, Julius Caesar, mad elephant, Royal Menagerie, Sir Robert Fossett's Circus, Tim Marshall Comments Off on Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, texts: Joanna Blachnio & Tim Marshall (4/4)Sir Robert Fosset’s Circus. © Tim Marshall 1984.

Joanna Blachnio writes:

Elephants in London have a long history. Tradition has it that Julius Caesar used a war elephant during his invasion of Britannia; he and his forces pitched camp not far from modern-day Bromley, so this un-named animal might be said to be the first pachyderm to impress suburban Londoners. In the 13th century, there was an African elephant amongst the Royal Menagerie which resided at the Tower of London – a gift from Louis IX of France. Plus, there is the elephant at the Elephant and Castle – although that area got its name from an 18th century coaching inn that stood in the vicinity.

One of the most poignant stories in the bestiary of London was that of Chunee, the mad elephant of Covent Garden. This sad creature arrived in Britain from India in 1809 as a theatrical and, later circus, animal, becoming one of the city’s attractions for almost two decades: even Lord Byron took note of his dexterity and good manners. He spent his dotage in the fabled menagerie at Exeter Change in The Strand, increasingly tormented by loneliness (there was no mate to help him while the time away) and a bad tusk. In February 1826, during his weekly parade down the Strand, Chunee rebelled against his captivity and went berserk, trampling one of his keepers in his rage. His temper did not subside and a death sentence was passed. The convict, however, clung on to life with the strength proportional to his body mass – almost seven tons. When they tried poisoning his food, Chunee was having none of that, and would not touch it. A troop of soldiers were sent for, yet even the fusillade from their muskets failed to kill the elephant, whose moans allegedly caused more distress than the sound of gunfire. Finally, one of his keepers ended his agony with a sword.

The elephants in Tim Marshall’s photograph are remote from the romance and pathos surrounding the death of their famous London ancestor. An impassive clown holding the curtain aside for their entrance, they take the stage with the weary docility of ageing pros. Their thick skin seems whitewashed in the glare of the stage lights. The last elephant to take to the ring can probably only sense what we are able to see: how much space there is in his wake.

Tim Marshall writes:

These photographs where taken in Easter 1984. At that time I was a student at Central St Martins School of Art making a life changing decision to stop illustrating with a pen and to start doing it with a camera.

I spent about four days photographing Sir Robert Fosset’s Circus. I remember going to Clapham Common at 8.00 in the morning, and before the circus site was in view hearing tigers roaring and elephants trumpeting, which was very surreal in central London. I photographed the tent being put up and only realized later that, everybody worked as a team and very hard. The tiger trainer helped put up the tent, starlets of the trapeze would, after finishing their acts, sell candy floss. Clowns empted bins. The clown Nelo, was not actually that funny and quite sad. Children would laugh at him rather than with him. He was a clown whose personal life seemed to be in complete disarray. But he wanted to be loved and make people happy.

After the show, I remember that certain pubs had a ‘no travellers‘ policy, so the people from the circus were refused entrance; and in the pubs they did manage to get into, they were only allowed in to the public bar rather than the lounge.

… for The London Column. © Joanna Blachnio, © Tim Marshall, 2012.