Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe. (3/5)

Posted: May 11, 2011 Filed under: Architectural | Tags: bicycle hoops, Greenwich Peninsula, Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, Owen Hatherley Comments Off on Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe. (3/5)Bicycle hoops, Greenwich Peninsula. Photo © David Secombe 2004.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain* by Owen Hatherley, 2010:

Within a few years, the area had taken on a definite identity, albeit not the one that was in the original brochure, and for most of the 2000s this was the place London forgot; a desolate landscape, one that was fascinatingly wrong, given the ecological and social-democratic ideas that had initially been thrown around in relation to it. A holding pen for Canary Wharf, yet somehow so much weirder than the usual Thames-side developments they inhabit. Alongside Erskine’s buildings – a staggered skyline of rendered concrete towers that would clearly be more at home in Malmö – was a nature reserve and a beach full of discarded shopping trolleys. The views were of industry either abandoned or clinging on, and pervaded by the sickly-sweet smell of the Tate & Lyle works. People were seldom seen, and the highways for cars en route to the Dome were utterly empty. Something resembling a dual hangar housed the ‘David Beckham Football Academy’ while concrete grain silos that would make Corbusier weep in admiration surveyed the area like sentries.

While this place was clearly a resounding failure on any social measure, it was a compellingly alien interzone in London’s cityscape. Neighbouring areas might be wracked by seething poverty and violence, but this enclave gave off a post-apocalyptic calm.

* published by Verso. © Owen Hatherley 2011

Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe. (2/5)

Posted: May 10, 2011 Filed under: Architectural | Tags: Greenwich Peninsula, Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, Owen Hatherley Comments Off on Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe. (2/5)Greenwich Peninsula, SE10. Photo © David Secombe 2002.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain*, Owen Hatherley, 2010:

The Greenwich Meridian just upriver made it an obvious centre for the Millennium Celebrations in 1999, so Major’s terminal Tory government drew up plans that were swiftly adopted by New Labour when they came to power in 1997. This time, though, the then vaunted Vision Thing would be key. Mike Davies at the Richard Rogers partnership, as it was then known, devised a PVC Tent that looked akin to a squashed version of the neighbouring gasholders, with yellow supports stretching themselves out like an industrial crown. The form was borrowed from an earlier, abortive master plan for the Royal Docks on the other side of the Thames, where several smaller tents were planned before the last recession. Initially devised as temporary, the tent’s PVC was demoted to Teflon when Green campaigners complained of ‘Waste’, landing them with a semi-permanent structure they would subsequently loudly abhor. Inside would be an exhibition divided into zones on culture, science, the body. When Blair’s government won the first Labour Landslide since Clement Attlee’s in 1945, some compared this Millennium Dome to the 1951 Festival of Britain, a parade of Modernist design and popular futurism mounted on the South Bank of the Thames. ‘Three dimensional socialist propaganda’ as it was called by Churchill, who hated and demolished it, leaving nothing after a Tory re-election but the Royal Festival hall, which would be encased in Portland stone in the 1960s to harmonize with the conservative restoration architecture of the Shell Centre.

Predictably, but no less sadly for that, things did not pan out that way. The Dome’s exhibition turned out to house a vast McDonalds and array of corporate advertainment, holding it up to a public ridicule that has only recently subsided.

* published by Verso. © Owen Hatherley 2011.

Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe (1/5)

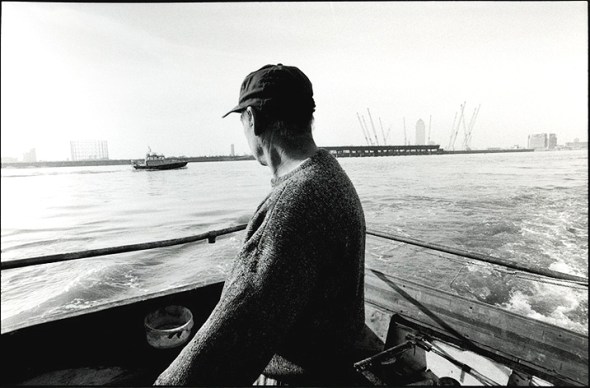

Posted: May 9, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, The Thames | Tags: Greenwich Peninsula, Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, Owen Hatherley Comments Off on Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe (1/5)The Dome under construction, seen from Bugsby’s Reach. Photo © David Secombe 1997.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain*, Owen Hatherley, 2010:

As recently as fifteen years ago, this place was called Bugsby’s Marshes. Downriver from Greenwich, with its baroque masterpieces and gift shops, a moonscape of blasted, smoking industry: the largest gasworks in the world, an internal railway ferrying goods and effluent from the river out to the suburbs, and a catalogue if toxic waste, known from the early nineteenth century as an area of ‘corrosive vapours’, something only added to by the autogeddon of the Blackwall Tunnel which sweeps a roaring fleet of cars under the Thames at rush hour.

In the post-industrial city, what we do with these places, with their memories of the grotesque mutations that ushered in its industrial precursor (after moving production out to China), is to clean them up and make them safe for property-owning democracy. Accordingly, by the 1990s this by now unproductive wasteland was ready for redevelopment, after a mammoth decontamination effort. Just over the river is an example of what this could have been like, the Canary Wharf development on the Isle of Dogs, where dead industry was rebranded in the 1980s as the ‘Docklands Enterprise Zone’. Architecturally, it was given the treatment pioneered in New York’s post-industrial Battery Park, a postmodernist simulation of a metropolis that never truly existed, populated by banks and newspapers. It even used the same architect, Cesar Pelli. Yet after the early 1990s recession, perhaps this as considered rather foolhardy for the Peninsula: at this point Docklands’ Stadtkrone at Canary Wharf (‘Thatcher’s Cock’ as it was nicknamed)was an empty, melancholic monument to neoliberal hubris, as opposed to today’s rapaciously successful second City of London. Something else had to be done: the ‘entertainment’ variant of the same schema swung into operation.

* published by Verso. © Owen Hatherley 2011.

See also: Flotsam and jetsam no. 5