Swansong.

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones 6 Comments Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

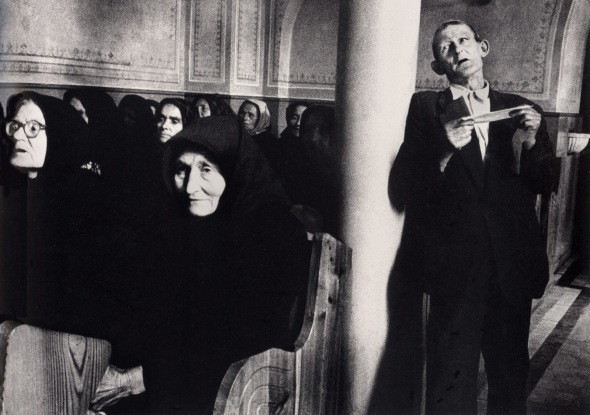

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

Balfronism.

Posted: September 10, 2014 Filed under: Architectural, Fictional London, Housing, London Places, Public Art | Tags: 007, 28 Days Later, Anthony Gormley, blackwall tunnel, Catherine Yass, east end, Erno Goldfinger, Goldfinger, High Rise, Hipster London, Ian Fleming, J.G. Ballard, Owen Hatherley, Robin Hood Gardens, Trellick Tower Comments Off on Balfronism. Red jumper, west flank, Balfron Tower. © David Secombe 2014.

Red jumper, west flank, Balfron Tower. © David Secombe 2014.

From Urbanism and Spatial Order by Erno Goldfinger, 1931:

From the point of view of the town, the individual is a mere brick in the spatial order of the street or square.

Thus sprach Erno Goldfinger, doyen of the Modern Movement, Brutalist visionary, Marxist voluptuary, and namesake of James Bond’s most memorable antagonist. (The story goes that Ian Fleming was unimpressed by the house Goldfinger built for himself in Hampstead, whose construction required the demolition of some pretty Victorian cottages. In revenge, Fleming appropriated the architect’s name for 007’s next outing; Goldfinger is supposed to have considered legal action.)

Service tower entrance, service corridors, Balfron Tower. © David Secombe 2014

Service tower entrance, service corridors, Balfron Tower. © David Secombe 2014

Goldfinger’s most conspicuous buildings in London are Elephant and Castle’s Metro Central Heights (formerly Alexander Fleming House, no relation), West Kensington’s Trellick Tower, and Trellick’s almost-identical East End counterpart Balfron Tower in Poplar. Trellick and Balfron are often cited as inspirations for J.G. Ballard’s dystopian classic High Rise, wherein the denizens of an exclusive tower block turn feral.

To some extent, Trellick Tower saw this narrative played out in reverse. Commissioned in 1967 as social housing for the London County Council, upon completion in 1972 Trellick quickly became a ‘problem’ estate. There was talk of demolition, it became a byword for urban grit (name-checked in The Sweeney no less) – but, facilitated by the gentrification of seedy/glamorous West London and an increased appreciation of the charms of ‘mid-century modern’, the tower gradually became a suitable address for aspirational professionals, and was Grade II listed in 1998 – two years after Balfron was.

Balfron Tower. © David Secombe 2014

Balfron Tower. © David Secombe 2014

Now it is east London’s turn. Balfron appeared first, topped-out in 1967 in an environment even more forbidding than old West Kensington. The location is still uncompromising: Balfron abuts the churning A12, feeding the Blackwall Tunnel just two hundred yards to the south. This piece of civic engineering affords majestic views of Balfron from the east and south but blights the lower floors facing the motorway. Balfron’s unprecedented height, hammered concrete finish, and stand-alone service tower with flying corridors and arrow-slit windows combine to give it a distinctly pugnacious aspect. The overall impression is of an urban fortress – a building fit to shelter the last bastions of humanity against marauding zombies (a role it plays in Danny Boyle’s 28 Days Later).

Balfron Tower west flank, from Chrisp St. © David Secombe 2014

Balfron Tower west flank, from Chrisp St. © David Secombe 2014

Balfron and its sister block, low-rise Carradale House (also by Goldfinger), are relics of a lost civic culture. There was a time not that long ago when modernity was a form of social utopianism. The East End had been blitzed, the residual housing stock was seen as Dickensian, and a clean, futuristic solution (Le Corbusier’s Unité d’habitation in Docklands) was an irresistible prospect for the ambitious bods at the LCC.

Balfron Tower was a brave project, and it took a fearless architect to see it through. It was intended to herald a dawn of new, better housing. Its flats meander up and down different levels, and the interiors are full of sensitive detailing. Goldfinger himself spent two months living in one of its penthouse flats, to evaluate the building; this led to important technical variations at Trellick when it was built a few years later. Amongst other things, he made sure Trellick had three lists instead of just two, after finding himself waiting twenty minutes for a lift to Balfron’s 27th floor.

Faced with accusations that his building constituted social engineering, he was robust: ‘I have created nine separate streets, on nine different levels, all with their own rows of front doors. The people living here can sit on their doorsteps and chat to the people next door if they want to. A community spirit is still possible even in these tall blocks, and any criticism that it isn’t is just rubbish.’

Balfron Tower from the east. © David Secombe 2014.

Balfron Tower from the east. © David Secombe 2014.

For all its elegance, sincerity, attention to detail, and integrity of construction, Balfron suffers from design flaws which mitigate the modernist dream: the lifts don’t serve every floor, concrete decay is an issue, and the uninsulated solid walls suffer from heat loss. However, the East End is being relentlessly gentrified, and Balfron is about to be transformed into a block fit for the well-heeled and design-conscious (let us call them hipsters). The old tenants have been decanted elsewhere for the works to begin, and before the tower gets its upscale makeover, Balfron has become a sort of temporary sink estate for artists – this in response to special cheap deals on the rent – who are softening the place up for a bourgeois and executive future.

Balfron Tower east flank (in the rain). © David Secombe 2014.

Balfron Tower east flank (in the rain). © David Secombe 2014.

The accepted rubric is that the artists ‘inject new life into communities’; and in recent times Balfron has itself become something of an installation. In 2010 it hosted an ’empowering’ photographic project, and this year has seen, amongst other things, a site-specific production of Macbeth, not to mention a bid by a Turner-prize nominated artist to throw a piano off its roof (abandoned after protests from residents that someone could get killed).

All this corporately-licensed conceptual ‘playfulness’ masks the fact that an important piece of public housing is being very deliberately annexed by the private sector. No longer a vision of better housing for a better future, Balfron is now the deadest of things: a design icon, a beacon for those who crave tokens of retro-urbanism. Owen Hatherley has coined the term ‘Gormleyism’ to describe the use of Antony Gormley’s solitary figures as cultural embroidery in bland civic developments; perhaps ‘Balfronism’ will become shorthand for the use of artists en masse as a form of social cleansing.

iPhone triptych, Balfron Tower from traffic on the A12. © David Secombe 2014.

iPhone triptych, Balfron Tower from traffic on the A12. © David Secombe 2014.

The patina of time makes quaint what was once brave, difficult, or merely awful. It won’t be long before ‘Ballardian’ is a term used by estate agents. D.S.

A Clockwork London. (2)

Posted: April 4, 2013 Filed under: Fictional London, Housing, London on film | Tags: A Clockwork Orange, Binsey Walk, Bird's Eye View, George Plemper, John Betjeman, Owen Hatherley, Stanley Kubrick, Thamesmead 1 CommentSouthmere Lake and Binsey Walk, Thamesmead. © George Plemper 1976.

George Plemper:

In late 1972 I made the journey to Leicester Square to see A Clockwork Orange. As with all Kubrick’s

films I thought the film was visually stunning and I loved the use of music throughout. The physical

and sexual violence seemed to me more theatrical than factual and I was astonished to hear a year

later the film had been banned.

All thoughts of the film had long gone when I crossed the footbridge across Yarnton Way

to Riverside School, Thamesmead in 1976. I had no idea I was entering a scene from Kubrick’s vision

of a desolate and violent Britain. My aims were simple; I was going to use the camera to show my

pupils that they were great, to show them that we were all worthwhile.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain by Owen Hatherley:

It’s impossible to praise the original Thamesmead without caveats. There were never enough facilities, the transport links to the centre were always appalling, and the development was always shockingly urban for its outer-suburban context. Regardless, it is something special, a truly unique place. It always was, and remains so in its current, amputated form.

Unlike its successors, it’s flood-proof and still architecturally cohesive, after decades of abuse. Around Southmere lake you can see, just about, how with some decent upkeep and with tenants being given the choice rather than being dumped here, this could have been a fantastic place … This is basically a working-class Barbican, and if it were in EC1 rather than SE28 the price of a flat would be astronomical. Today it feels beaten and downcast, and it only ever gets into the news through vaguely racist stories about the Nigerian fraudsters apparently based here; but its architectural imagination, civic coherence and thoughtful detail, its nature reserves and wild birds, have everything that the ‘luxury flats’ lack.

Southmere Lake and Binsey Walk today. © David Secombe 2013.

Where Alex walked … watch him pitch his droogs into the cold, cold waters of Southmere Lake here.

See also: Pepys Estate 1, Pepys Estate 2, Domeland, Metro-Land.

Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Owen Hatherley (2/3)

Posted: May 18, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Interiors | Tags: Owen Hatherley, Pepys Estate, RIBA, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Owen Hatherley (2/3)Elderly resident, Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo Tony Ray-Jones © RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Owen Hatherley writes:

Like a lot of council estates that have been subjected to the ministrations of ‘regeneration’, there are certain myths about the Pepys Estate. Each has a grain of truth, each covers up what ought to be a larger, more overwhelming truth.

My own experience of the place is fairly limited. I recall walking there from a flat in the centre of Deptford to hand in my form for the council waiting list; on a few other occasions I would wander over to use the bridge that connected the estate to Deptford Park, just for the fun of it, for the fact of its mere existence. The place seemed quiet during the day; I only saw it at night as the N1 bus looped around it. So I can’t offer much insight into what it was ever like to live there, but I have watched the material transformations of the place over the last decade or so, and watched the media discourse around it spin its web.

The Pepys is often presented as a monolithic, monstrous estate that was a failure from day one. Which is interesting, as the place marked one of the earliest council schemes to preserve as well as demolish – the little enclaves of Georgian nauticalia that mark the estate’s edges were part of the scheme, renovated and let by the council as an integral element, by now surely long since lost to Right to Buy. The rest of it is, or rather was, a series of jagged, mid-rise blocks connected by walkways, enclosing three towers and a large open space, with the bridges eventually leading to a park on the other side of Evelyn Street. In the middle is a community building with a bizarre, expressionist roofline seemingly partly based on oast houses (but then, so is Bluewater).

What is undoubtedly true is that parts of it were badly made – the lifts were apparently prone to breakdown from extremely early on. The draughty blocks were clad in plasticky white material at some point in the 1980s. Yet what happened when the place got ‘regenerated’ is by far the most dramatic aspect. The open space went, with low-rise flats to be sold to ‘key workers’ and on the open market taking an already highly dense area and making it more so. This accordingly makes it more ‘mixed’, ‘vibrant’ and ‘urban’, as professionals now live alongside – well, not quite alongside, but at least near to, council tenants.

The bridge over Evelyn Street went also, with remarkably clumsy ‘eco-flats’ (you can tell this, because the extra layer of curved glass on the façades a few feet from the actual windows could surely have no other possible functional justification) built where it met the park. This ‘recreated a street pattern’ in the area according to planning ideologists; or it defaced an area of public space. As you wish.

The new blocks are regeneration hence good, the old are council housing hence bad. Yet the council flats are much larger, and look much more robustly built, of concrete and stock brick – the newer flats are clad in the ubiquitous thin layer of brick or attached slatted wood, materials which have shown an unfortunate tendency to fall off. The major story is with one of the three towers – the one nearest to the river, naturally – which was completely cleansed of undesirables and sold instead as Z Apartments, luxury riverside living. It became a brief cause celebre via class war reality TV show The Tower.

All this, in theory, funds the regeneration, meaning in this case the cleaning and patching up, of the older buildings, or alternatively to their phased, currently seemingly stalled, demolition. None of the new buildings in the Pepys Estate – or anywhere else in London – have been council housing, though its regeneration has entailed several once council flats going private. The waiting list, nationally, is reckoned to be five million.

… for The London Column. © Owen Hatherley 2011.