At Home with Mrs John Profumo.

Posted: March 25, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Class, Corridors of Power, Events, Housing, Interiors, London scandals | Tags: Chester Terrace, Christine Keeler, Evening Standard Homes and Property, House and Garden, John Profumo, London property market, Profumo Affair, Scandal, Stephen Ward, Toynbee Hall, Valerie Hobson Comments Off on At Home with Mrs John Profumo.‘Mrs Profumo in the drawing-room with her white French faience hound.’ Uncredited photo from House and Garden, Conde Nast Publications, 1962.

From The House and Garden Book of Interiors, 1962:

Mr. and Mrs. Profumo (she is Valerie Hobson, the actress) live in a typical-looking Regent’s Park stuccoed villa, which has certain highly individual touches, the most covetable being a large garden and a magnificent drawing room.

An improbably large area of the house is given over to the drawing room, which must be one of the largest rooms in London to be found in a house of comparatively modest size. With its double-cube proportions, three fine windows, opening on to the garden, and gaily disciplined Nash decorations, this is a perfect room for a couple who must, perforce, engage in a great deal of entertaining.

A quick glance into Mr. Profumo’s own study provokes the wish that more masculine, magisterial ministerial rooms were half so attractive! Needless to say, the desk is large and if you look carefully you will see a highly decorative as well as highly confidential red ministerial despatch box on it, doubtless often impelling the owner of this charming house away from the family circle to the chores inseparable from high office.

From John Profumo’s statement in the House of Commons, 22nd March, 1963:

“My wife and I first met Miss Keeler at a house party in July 1961 at Cliveden. … Between July and December 1961, I met Miss Keeler on about half-a-dozen occasions at Dr Ward’s flat, when I called to see him and his friends. Miss Keeler and I were on friendly terms. There was no impropriety whatsoever in my acquaintanceship with Miss Keeler. … I shall not hesitate to issue writs for libel and slander if scandalous allegations are made or repeated outside the House.”

From Confessions of Christine, Christine Keeler, News of the World, June 1963:

Our meetings were very discreet. Jack [Profumo] drove a little red mini car. … If we were not in the flat, then we would just drive and drive for hours. Of course, it was impossible that our discretion would be absolutely complete. There was that amazing evening when Jack was round, and an army colonel showed up suddenly looking for Stephen [Ward]. The colonel couldn’t believe it. Jack nearly died. The funny thing is I never used to think of Jack as a Minister. I can not bow down to a man who has just got money or a position. And I liked Jack as a MAN.

David Secombe:

The passage of time has rendered the uncredited House and Garden text as poignant as it is comic. The gushing prose is at odds with the attitude of Valerie Hobson in the picture, lost amidst the chilly perfection of her vast drawing-room. Her husband, despite his vivid presence in the editorial copy, fails to appear in any of the pictures of the interior of their Regency villa, presumably due to the demands of the business of state – or, as implied by Christine Keeler’s racy memoir, some other kind of business.

This issue of House and Garden appeared in 1962, not long before Profumo’s mendacious statement to Parliament, which left a host of hostages to fortune, eventually leading – as everyone knows – to his resignation as Secretary of State for War. Today, politicians have ample opportunities to reinvent themselves after a career-ending debacle: Neil Hamilton, Jonathan Aitken and even Jeffrey Archer have achieved a degree of rehabilitation and it seems likely that Chris Huhne and Vicky Pryce will eventually re-enter ‘public life’ in some form or other. As the pioneer of modern political scandal, John Profumo had no such option: instead, he chose a practically Roman form of self-abasement, cleaning the toilets at Toynbee Hall in Whitechapel (a task he continued to do until the management suggested that there might be better ways of using his skills). He did, eventually, gain a limited re-admittance into high society but even that took him decades.

Former home of Mr. and Mrs. John Profumo, Chester Terrace. Photo © David Secombe 2011.

From Evening Standard Homes and Property, 14 Feb 2012:

This Grade I-listed property at prestigious Chester Terrace overlooking Regent’s Park, was once the home of shamed politician John Profumo, who lived in the splendid stucco townhouse during his much-publicised affair with model Christine Keeler in the Sixties. The scandal forced his resignation as secretary of state for war and damaged the reputation of Harold Macmillan’s government. Designed by John Nash, the architect responsible for much of Regency London, the elegant, four-bedroom house now has a cinema room, wine cellar and enchanting garden. If only walls could talk… Call [estate agent] if you have £10.95 million.

Up My Street. Photo: Dylan Collard (3/5)

Posted: September 26, 2012 Filed under: Class, Eating places, Food, Lettering, London Labour, Public Announcements | Tags: Dylan Collard, gentrification, Hipster hordes, Hipsterism, Holloway Road, The Archway Cafe Comments Off on Up My Street. Photo: Dylan Collard (3/5)The Archway Cafe. © Dylan Collard.

David Secombe writes:

The genius of photography is the commemoration of the ephemeral; this is the reason why some of us are beady on the subject of digital photography, as it represents the commemoration of the ephemeral by means of the even-more-ephemeral. No such qualms arise from this week’s images by Dylan Collard, which were made using defiantly old-school methods. For his photos documenting the Holloway Road, Dylan lugged his massive Gandolfi ‘field’ camera (a device the size of a large hatbox, bolted to a hefty tripod) up and down that windswept, Stalinist boulevard to record scenes as quotidian as one could imagine.

In today’s photo, the proprietor (it can be no-one else) of the Archway Cafe poses for the camera in a way that we believe – we know – to be characteristic. Of course, he is having us on; he is playing the part of a surly cafe owner for our benefit, he knows that he is being memorialised for posterity – and Dylan’s limpid image preserves the shrewd glance of this short-order chef as if in amber.

Yet, if current trends continue, this commonplace scene is likely to disappear within a few years. The formica and the plastic condiment bottles already look like period pieces in this context, where they are employed as functional items rather than archly retro decor. This is not a cafe for budding screenwriters with their MacBook Pros, or middle-class mums with Range Rover-sized prams and Orla Kiely infants, but it can only be a matter of time. The hipster-friendly make-over of the Holloway Road is upon us with the inevitability of a melting ice shelf. And perhaps that is why our man in the Archway Cafe is so watchful, he might be keeping an eye out for the wrecking hordes: the girls with oversized glasses, cut-off shorts and day-glo leggings, the thin young men with buttoned-up plaid shirts, skinny jeans and implausibly bushy boybeards … an army of destruction as potent as any in history.

… for The London Column.

Up My Street is Dylan Collard‘s project documenting shops between Kentish Town and Archway. His exhibition The Twelfth Man is currently showing at Exposure Gallery, 22-23 Little Portland Street, London W1. Dylan is represented by the Vue agency.

Ridgers reminisces. Photo & text Derek Ridgers (2/5)

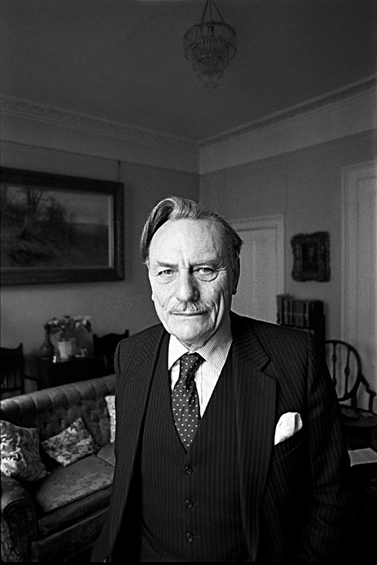

Posted: November 29, 2011 Filed under: Class | Tags: Enoch Powell, New Musical Express, Rivers of Blood, Stephen Wells Comments Off on Ridgers reminisces. Photo & text Derek Ridgers (2/5)Enoch Powell, Eaton Square, 1984. Photo © Derek Ridgers.

Irrespective of his ridiculous views on race relations, Enoch Powell was certainly one of my strangest ever subjects.

I was commissioned to photograph him by the NME and, together with the writer Mat Snow, we turned up at his very grand flat in Eaton Square to meet a guy who seemed determined, for some reason, to try to make us laugh. For someone who achieved a starred double-first from Cambridge University, and who was often referred to as the greatest political mind of his generation, he struck me as a bit of a twit. To start with, he began by deriding my accent and the way I talk. He enquired as to whether I might be an Australian? I’m a Londoner, born and bred and though my accent isn’t of the typical gor-blimey cockney variety, it’s never (outside of the US) ever confused anyone before. Then he asked me about the origins of my name and started to try to find something funny about that. Next he spoke to a woman who had been detailed to bring us some tea and called her “dear” and invited us to speculate on what his precise relationship with her was (it was his wife). All the while he was grinning at us like Sid James in a Carry On film.

His desire to trivialise the situation must, I guess, have been some sort of bizarre tactic to make us forget to ask him anything remotely serious. It was a little patronising of him and it didn’t work. Mat Snow was far too canny an interviewer for that and he managed to ask him all the questions I’m sure he would rather have not been asked. Mat Snow writes “being interviewed as he was by New Musical Express, rather than await my questions he launched straight into an interminable monologue about Nietzsche and his philosophy of music, and seemed rather put out when I tried to get the interview back on track by asking him if perhaps his infamous ‘rivers of blood’ UK race war prediction of 1968 was perhaps a tad wide of the mark as things had panned out by then.”

Enoch Powell was a proud man but, in my judgement, by this stage of his political career, a little sad.

© Derek Ridgers. From The Ponytail Pontifications.

Homer Sykes: Britain in the 1980s. Text by Charles Jennings. (5/5)

Posted: September 23, 2011 Filed under: Class, Sartorial Comments Off on Homer Sykes: Britain in the 1980s. Text by Charles Jennings. (5/5)Jumble sale, Dulwich, circa 1980. Photo © Homer Sykes/Photoshelter.

Make Do and Mend

Between The Buttons: What Mothers Can Do To Save Buying New. (I got up so late I only had time to put on me flippin’ slacks )

A woman sat, in unwomanly rags (Our backs were covered up, more or less, but the other way round was a big success). But what went ye out for to see? A man clothed in soft raiment.

Recycled Clothing Sculpture Making Project: My shirts are made from Mum’s old drawers.

It depends how many boots he’s got to mend. I brought him home six and a half pairs today.

The handbags and the gladrags: These fragments I have shored against my ruins

(Taken from: Gert & Daisy; The Rag Trade; Make Do And Mend; Thomas Hood; Matthew, xi 7; The Goon Show; The Rolling Stones; Steptoe & Son; Rod Stewart; T. S. Eliot)