London Perceived. Text V.S. Pritchett, photos Evelyn Hofer (3/5)

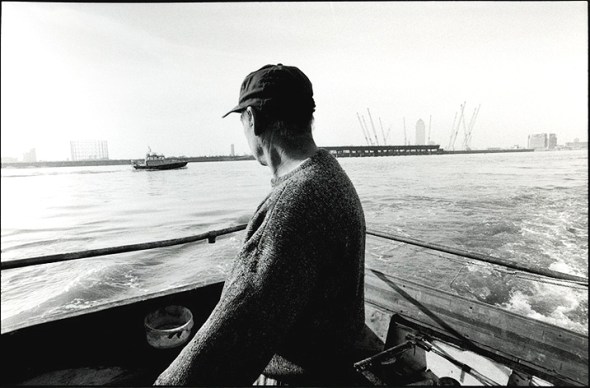

Posted: July 27, 2011 Filed under: London Labour, The Thames | Tags: Evelyn Hofer, London Perceived, Pool of London, V.S. Pritchett Comments Off on London Perceived. Text V.S. Pritchett, photos Evelyn Hofer (3/5)The Thames: Upper Pool, 1962. Photo © Estate of Evelyn Hofer.

V.S. Pritchett writing in London Perceived*, 1962:

Twenty-three miles of industrial racket, twenty-three miles of cement works, paper-mills, power stations, dock basins, cranes and conveyors shattering to the ear. From now on, no silence. In the bar at thre Royal Clarence at Gravesend, once a house built for a duke’s mistress, it is all talk of up-anchoring, and everyone has an eye on the ships going down as the ebb begins, at the rate of two a minute. The tugs blaspheme. One lives in an orchestra of chuggings, whinings, the clanking and croaking of anchors, the spinning of winches, the fizz of steam, and all kinds of shovellings, rattlings, and whistlings, broken once in a while by a loud human voice shouting an unprintable word. Opposite are the liners like hotels, waiting to go to Africa, India, the Far East; down come all the traders of Europe and all the flags from Finland to Japan. You take in lungfuls of coal smoke and diesel fume; the docks and wharves send out stenches in clouds across the water: gusts of raw timber, coal gas, camphor, and the gluey, sickly reek of bulk sugar. The Thames smells of goods: of hides, the muttonish reek of wool, the heady odours of hops, the sharp smell of packing cases, of fish, frozen meat, bananas from Tenerife, bacon from Scandanavia,

Before us are ugly places with ancient names where the streets are packed with clownish Cockneys and West Indian immigrants, the traffic heavy. Some of them on the north side between Tilbury and Bethnal Green are slums, dismal, derelict, bombed; some of them so transformed since 1940 by fine building that places with bad names – Ratcliff Highway and Limehouse Causeway and Wapping – are now respectable and even elegant. The old East End has a good deal been replaced by a welfare city since 1946. We pass Poplar, Stepney, Shadwell, Deptford, Woolwich, the Isle of Dogs – where Charles II kept his spaniels – and now mostly dock, with the ships’ bows sticking over the black dock walls and over the streets. We pass Cuckold’s Point, where one of the kings of England gratified a loyal innkeeper by seducing his wife. Until the sixteenth century – according to the delightful Stow, who said he “knew not the fancy for it” – a pair of horns stood on a pole there, a coarse Thames-side warning, perhaps, of the hazards that lie between wind and water.

The Thames, we realize, was for centuries London’s only East to West road or, at any rate, the safest, quickest, and most convenient way that joined the two cities, one swelling out from the Tower and the other from Westminster. And there is another important matter. It is hard now to believe as we go past these miles of wharves and the low-built areas of dockland where one place now runs into another in a string of bus routes, but this mess was once royal. The superb Naval College at Greenwich is the only reminder. It is built on the site of the Palace of Placentia, where Henry VIII, the great Elizabeth and Mary were born. Here was the scene of the luxurious Tudor pageants, the banquetings that went on for weeks, the great wrestling bouts, the tournaments, the displays of archery. It is from “the manor of East Greenwich” and not from Westminster that the charters to Virginia and New Jersey were given in the seventeenth century. It is odd that London began as a collection of manors and that the word “manor” is still thieves’ slang for “London”. At Deptford, nearby, was the Royal Naval Dockyard where all the Tudor ships were built – Drake’s Golden Hind was laid down here. One can see the reason. It is not simply that the Tudors liked building palaces, just as the aristocracy liked building mansions that vied with those of the kings. It is not simply that English monarchs have been a restless lot, although that is true too. The plain reality is that a monarch who has been churched at Westminster needs money; he has to get it from the City; the City gets it from ships and trade, and that trade and its ports must be defended by navies. Deptford and Greenwich were close to London’s fortune, where the goods came in, whence the adventurers sailed, and where the attackers attacked.

* © 1962 and renewed 1990 by V.S. Pritchett. Used by permission of David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.

[Special thanks in assembling this week’s feature are due to: Jim McKinniss; Mark Giorgione of the Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California; Andreas Pauly at the Hofer Estate; and Carl Scarbrough at David Godine. D.S.]

Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe (1/5)

Posted: May 9, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, The Thames | Tags: Greenwich Peninsula, Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, Owen Hatherley Comments Off on Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe (1/5)The Dome under construction, seen from Bugsby’s Reach. Photo © David Secombe 1997.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain*, Owen Hatherley, 2010:

As recently as fifteen years ago, this place was called Bugsby’s Marshes. Downriver from Greenwich, with its baroque masterpieces and gift shops, a moonscape of blasted, smoking industry: the largest gasworks in the world, an internal railway ferrying goods and effluent from the river out to the suburbs, and a catalogue if toxic waste, known from the early nineteenth century as an area of ‘corrosive vapours’, something only added to by the autogeddon of the Blackwall Tunnel which sweeps a roaring fleet of cars under the Thames at rush hour.

In the post-industrial city, what we do with these places, with their memories of the grotesque mutations that ushered in its industrial precursor (after moving production out to China), is to clean them up and make them safe for property-owning democracy. Accordingly, by the 1990s this by now unproductive wasteland was ready for redevelopment, after a mammoth decontamination effort. Just over the river is an example of what this could have been like, the Canary Wharf development on the Isle of Dogs, where dead industry was rebranded in the 1980s as the ‘Docklands Enterprise Zone’. Architecturally, it was given the treatment pioneered in New York’s post-industrial Battery Park, a postmodernist simulation of a metropolis that never truly existed, populated by banks and newspapers. It even used the same architect, Cesar Pelli. Yet after the early 1990s recession, perhaps this as considered rather foolhardy for the Peninsula: at this point Docklands’ Stadtkrone at Canary Wharf (‘Thatcher’s Cock’ as it was nicknamed)was an empty, melancholic monument to neoliberal hubris, as opposed to today’s rapaciously successful second City of London. Something else had to be done: the ‘entertainment’ variant of the same schema swung into operation.

* published by Verso. © Owen Hatherley 2011.

See also: Flotsam and jetsam no. 5