The London Nobody Knows – revisited. Photos & text: David Secombe (1/4)

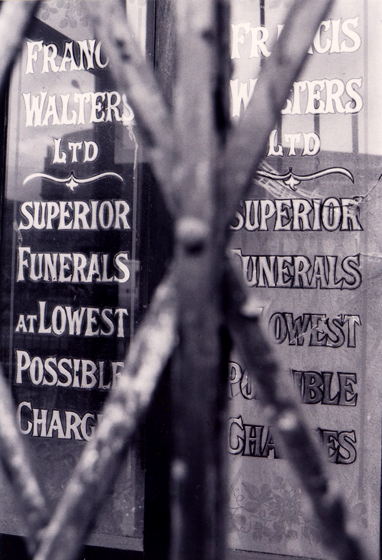

Posted: June 19, 2012 Filed under: Dereliction, Literary London, Shops, Vanishings | Tags: Geoffrey Fletcher, limehouse, superior funerals, The London Nobody Knows, undertaker Comments Off on The London Nobody Knows – revisited. Photos & text: David Secombe (1/4)Limehouse. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

From The London Nobody Knows, Geoffrey Fletcher, 1962:

My chief pleasures in Limehouse are confined to a small area, centering on the church of St. Anne. The undertaker’s opposite the church is a rare example of popular art. Even today, East End funerals are often florid affairs – it is only a few years since I saw a horse-drawn one – but such undertaker’s as [the one in the above photo] must be becoming rare, so it is worth study. It is hall-marked Victorian. The shop front is highly ornate and painted black, gold and purple. Two classical statues hold torches, and there achievements of arms in the window and also inside the parlour. The door announces ‘Superior funerals at lowest possible charges’. On one side of the window is a mirror on which is painted the most depressing subject possible – a female figure in white holding on (surely not like grim death?) to a stone cross and below her are the waves of a tempestuous sea. Inside the shop are strip lights – the only innovation to break up the harmony of this splendid period piece – a selection of coffin handles and other ironmongery and a photograph of Limehouse church. As I looked, a workman, with a mouthful of nails, was hammering at a coffin. An unpleasant Teutonic thought occurred to me that, at this very moment, the future occupant of the coffin might well be at home enjoying his jellied eels . . . Undertaker’s parlours of such Victorian quality must be enjoyed before it is too late. This one mentioned is, I believe, the best in London. People stare through the windows of undertakers – at what? Unless they are connoisseurs of Victoriana there seems to me little beyond the elaboration of terror and a frowsy dread that has no name.

David Secombe:

The shop Geoffrey Fletcher rhapsodised over fifty years ago remains in situ opposite St. Anne’s, but is now derelict. When I took this photo a couple of years ago, it was possible to see the remnants of the shopfront, but a matter of days later the entrance was boarded up and the last remnant of the Victorian throwback that Fletcher described with such relish disappeared from view. This week we are running a small selection of excerpts from Fletcher’s classic, alongside contemporary views of the sights he delineated so lovingly. Fletcher’s book is a kind of requiem for an older, more private city – and although his fears about the fate of many individual buildings proved to be unfounded, Londoners are faced with a new wave of monolithic redevelopment. In our current era of corporate-sponsored ‘regeneration’, the final words of the book seem truer than ever: ‘Off-beat London is hopelessly out of date, and it simply does not pay. I hope, therefore, that this book will be a stimulus to explore the under-valued parts of London before it is too late, before it vanishes as if it had never been. The old London was essentially a domestic city, never a grandiose or bombastic one. Its architecture was therefore scaled to human proportions. Of the new London, the London of take-over bids and soul-destroying office blocks, the less said, the better’.

… for The London Column.

Incredible Londoners. Photo & text: David Secombe.

Posted: May 18, 2012 Filed under: Artistic London, London Music, Pubs, Vanishings | Tags: incredible Londoner, Jerusalem Tavern, Johno Driscoll, Thomas Britton 4 CommentsJerusalem Tavern and Jerusalem Passage, Britton Street, Clerkenwell. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

This week’s sad news has prompted some of us to remember pub crawls with John on his patch, and the names of the hostelries we’d encounter on the way: The Horseshoe in Clerkenwell Close, The Crown on Clerkenwell Green, The Coach and Horses in Ray Street, The Marie Lloyd in Hoxton, The Eagle on Farringdon Road, the Sekforde Arms on Sekforde Street – and, now and again, The Jerusalem Tavern on Britton Street. As this week we have been remembering a great Londoner and champion of art, it seems oddly fitting to add this nugget about an artistic promoter who operated in the same area 300 years ago, and who is now buried in Clerkenwell churchyard. D.S.

From Without the City Wall, Hector Bolitho and Derek Peel, 1951:

Britton Street was named after an incredible Londoner of the late 17th century who walked the streets by day “in his blue frock coat and with his small coal-measure in his hand”, and who by night gave concerts in his humble abode next to Jerusalem Tavern, in what is still Jerusalem Passage. In The London Magazine we read: “On the ground floor was a repository for small coal; over that was a concert room, which was very long and narrow. … Notwithstanding all, this mansion attracted to it as polite an audience as ever the opera did.. … At these concerts Dr. Pepusch and frequently Mr.Handel played the harpsichord.” When passing along the streets with his sack of small-coal on his back, Thomas Britton “was frequently accosted with such expressions as these: ‘There goes the famous small-coal man, who is a lover of learning, a performer in music and a companion for gentleman.’”

Hockley Hole, AKA Central Saint Martins. Photo & text: David Secombe.

Posted: May 16, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Artistic London, Bohemian London, Public Art, Vanishings | Tags: Back Hill, Central Saint Martins, Common People, Hockley in the Hole, John Driscoll, Johno's Darkroom 2 CommentsBack Hill, 2010. © David Secombe.

From The Fascination of London: Holborn and Bloomsbury, edited by Sir Walter Besant 1903:

The lower part of Saffron Hill was known at first as Field Lane, and is described by Strype as “narrow and mean, full of Butchers and Tripe Dressers, because the Ditch runs at the back of their Slaughter houses, and carries away the filth.” Just here, where Back Hill and Ray Street meet, was Hockley Hole, a famous place of entertainment for bull and bear baiting, and other cruel sports that delighted the brutal taste of the eighteenth century. One of the proprietors, named Christopher Preston, fell into his own bear-pit, and was devoured, a form of sport that doubtless did not appeal to him. Hockley in the Hole is referred to by Ben Jonson, Steele, Fielding, and others. It was abolished soon after 1728. All this district is strongly associated with the stories of Dickens. In later times Italian organ-grinders and ice-cream vendors had a special predilection for the place, and did not add to its reputation.

David Secombe writes:

One might add that in the 20th century, the area described above became associated with the photographic profession: at one time Clerkenwell was said to have more darkrooms and studios per square foot than anywhere else in the world. As a coda to yesterday’s post remembering the great Johno Driscoll, here’s a picture of ‘found art’ posted to the wall of John’s old premises, Holborn Studios, which is now a campus for Central Saint Martins art college. The building is situated within ‘the Hole’ – although the site of the bear-pit itself is now occupied by the pub opposite, The Coach and Horses. (Allegedly, the pub once afforded access to the Fleet river from its cellars, providing 18th Century fugitives with an escape route to the Thames.) Somehow, it seems right and proper that one of the most disreputable spots in 16th and 17th Century London should have gone on to be associated with photography, fashion, and art: the favoured trades of chancers, ne’er-do-wells and diamond geezers.

… for The London Column. See also: Little Jimmy, King of Clerkenwell.

Johno Driscoll. Photo: Tim Marshall, text: David Secombe.

Posted: May 15, 2012 Filed under: London Types, Street Portraits, Vanishings | Tags: Craig McDean, Eamonn McCabe, Elaine Constantine, fine art printing, Johno's Darkroom, Nick Knight, Sean Smith 20 CommentsJohn Driscoll, outside the Horseshoe, Clerkenwell Close, 2011. Photo © Tim Marshall.

David Secombe writes:

Any photographer who came of age in the pre-digital era can still summon up the clammy, vertiginous mix of excitement and fear which attended a trip to the darkroom to review the results of a shoot. Most London labs (invariably located in basements) reeked of fixer and testosterone: some establishments referred to their clients as “the enemy”, and any cock-ups or infelicities on the part of the photographer left the hapless smudger open to mockery, abuse and, it was rumoured, actual physical violence from short-tempered darkroom staff. This added a certain nervous tension to the experience of checking out your film. But there were some noble exceptions to this rule.

John Driscoll, who died on Monday, was the proprietor of the legendary Johno’s Darkroom – black and white only – an establishment supreme of its kind, its reputation resting on John’s brilliance as a printer and warmth as a human being. On any given day from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, a bewildering array of images would pass through Johno’s – haute couture, music, hard news, fine art – but whatever the subject, all John’s prints bore that exquisite, luminous quality which made him the printer of choice to the likes of Nick Knight, Craig McDean, Elaine Constantine, Eamonn McCabe, Sean Smith, and many, many others. His printing technique was matched only by his generosity and enthusiasm for the work of the photographers he admired.

Johno’s was a sort of club for the profession. You’d wait for John to finish your prints, swap notes with other photographers, sneak a look at pictures other people had brought in and inwardly (and occasionally outwardly) remark upon the quality of them. You’d exchange stories and bad jokes with his colleagues Jason and Paul (later it was Barb and Cherie), and glimpse John emerging from the dark now and again to take a call, retouch a print or send someone to the bookie’s with a hot tip and a tenner. When all the rush jobs were cleared, we’d migrate to pubs in pre-gentrification Clerkenwell or Hoxton (John was based in Hoxton Square for much of the early 1990s, and his darkroom was next door to where White Cube stands today), where John had to be forcibly prevented from buying every round. Very often, his wife Barbara – the other half of the Variety double act – would be at the lab, and could usually be persuaded to come out for a drink: much shouting and hilarity and missing of trains home would ensue. Everyone felt good around John, he could energise a room simply by walking into it.

The best photographers went to him because he was the best, but all the bullshit surrounding the profession fell away when you were in his company. Some photographers might be prima donnas in the wider world, but no-one outshone John in his own domain. And it was unwise for, ah, naive photographers to treat John as just some kind of tradesman; more than one photographer was shown the door because John thought his or her work was fraudulent. Yet, for some of his clients, John was prepared to do much more than just turn out lovely prints. Occasionally, John would receive rolls of film from some flailing, desperate young photographer, fearing disaster after a fraught shoot on a big assignment. In a war film, John would have been the cheerful sergeant steadying the nerves of an inexperienced officer: if John was on your side, you were all right. He’d get you through. He was the relief column. There are a number of very successful photographers who have very good cause to be grateful to John. He inspired tremendous loyalty. We weren’t his clients: we were his devotees.

John first went to work in New York around the Millennium. It was at the request of Craig McDean, who had him flown out at the expense of a client as he was the only black and white printer who could do Craig’s pictures justice. He ended up founding Johno’s NY and stayed in the US until the rise of digital eroded the market for traditional printing, retiring to Brighton only a few years ago. Of course, he wasn’t really retired, he was looking to get a darkroom going on the south coast, or a gallery maybe – somewhere where he could share his love of photography and showcase the work of his friends and clients, a place to show “all those wonderful images that need to be seen”.

With grim irony, I learnt of John’s death on the same day as I heard of a new digital camera from Leica: the ‘Monochrom’. It only takes black and white images – the idea is that a digital chip will duplicate the look of the finest black and white photographs. It’s worth stopping to consider the proposition: that a piece of hardware can replace the care and dedication which transforms a negative on a piece of celluloid into a work of art on paper. I can’t see it myself.

I think of John casually producing a box of prints he’d made from my negatives, and asking if I was happy? The prints glowed from within. I was so grateful I wanted to cry. I’d grabbed a few pictures in difficult conditions for a demanding client and he’d turned them into objects of beauty (saving my arse in the process). You can’t replace that with a chip. An age is passing and we are the poorer for it. I grieve for an irreplaceable friend.

… for The London Column. © David Secombe 2012.