Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (4/5)

Posted: December 8, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Wildlife Comments Off on Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (4/5)Bactrian Camel, Zoo Series, London 1992. © Britta Jaschinski.

Randy Malamud writes:

Zoos are obviously bad for animals, cruel to animals, but beyond that, they’re bad places for people to learn how we relate to the other creatures with whom we share the planet. Zoos are a case study of people’s environmental short-sightedness. After and beyond the experience of zoogoing, people behave like imperious emperors toward the rest of the world, overconsuming, unsustainably harvesting plants, animals, minerals, oil, land, and yet remaining in denial about our impact on the planet. Our disregard for animals, our displacement of them, betokens a larger environmental hubris, or blindness. Zoos promote sloppy, imperial animal-looking and animal-thinking, which generates a sloppy, self-serving, inauthentic environmental sensibility. To confront overarching questions about how people construct and interact with “the environment,” a consideration of zoos offers a good ingress. The cultural history of the zoo is a history of human assaults upon other animals, and upon the rest of nature. Zoogoing is a model of imperial exploitation of the natural world.

Zoos exist because people want to make animals conveniently accessible and visible, but there is nothing convenient about wild animals. They are complicated, enigmatic, entropic. Jaschinski’s photography embraces this complexity, and subverts our urge to simplify and reduce their lives.

© Randy Malamud.

Zoo by Britta Jaschinski is published by Phaidon.

Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (3/5)

Posted: December 7, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Wildlife | Tags: Brutalism, London Zoo Comments Off on Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (3/5)Asian Elephant, Zoo Series, London 1992. © Britta Jaschinski.

Randy Malamud writes:

Zoo animals are removed from their own contexts, their own habitats, and resituated in a context that makes it more convenient for spectators to see them. The disjunction between where an elephant really lives and this Regent’s Park pied-a-terre is surreal. Zookeepers tell their audiences that the point of zoos is for people to establish connections with other animals, and to inculcate a sense of ecological awareness as human expansion threatens animal habitats. But paradoxically – perversely – the zoo features animals divorced from their world.

The elephant people see in the zoo is not a “real” elephant. The real elephant lives in her place, in her habitat, in her environment, among and alongside many other animals of her own species, as well as many animals of other species, predators and prey, friends and strangers. She lives there because her lifecycle is predicated upon a certain seasonal climate, a certain range of movement, an environment comprised of certain plants, trees, water, dirt, stones, topography, and so forth. It is fundamentally impossible for zoos to reproduce any significant amount of this animal’s habitat.

As people expressed feeling of guilt about seeing caged animals in prison, some zoos began to modify the enclosures, largely to alleviate the spectator’s discomfort. Perhaps the designers who created this brutalist elephant compound thought that the “brutes” inhabiting it would feel at home here. But the zoo’s architectural spectacles do not alter the fact that the constrained animal on display lacks most aspects of the environment in which he or she naturally lives. Zoo-goers cannot see an elephant who acts or feeds or sleeps or eats or mates or nurtures or fights in the way a real elephant would. Depressive, anxious, and fearful behaviour – learned helplessness, self-injury, stereotypic repetition — is rampant among captive animals on display.

© Randy Malamud.

Zoo by Britta Jaschinski is published by Phaidon.

Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (2/5)

Posted: December 6, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Wildlife | Tags: London Zoo, Regent's Park, Sir Stamford Raffles Comments Off on Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (2/5)Black-Footed (Jackass) Penguin, Zoo Series, London 1995. © Britta Jaschinski.

Randy Malamud writes:

Walking in the Zoo, walking in the Zoo.

The O.K. thing on Sunday is the walking in the Zoo.

So sang Victorian music-hall artist Alfred Vance – the Great Vance! – in 1870, appearing as a dandy London “swell” recounting his excursion to Regent’s Park. The Fellows of the Zoological Society of London were not amused by his contribution of the word “zoo” to the lexicon, dismayed that the common monosyllabic moniker trivialized their importance.

“ZSL London Zoo,” as it calls itself today, opened to the Fellows of the Society in 1828, and to paying visitors from the public at large in 1847. Some of its cages (or “enclosures,” in today’s softer euphemism of zoo discourse) date back to that era: the Raven’s Cage was erected in 1829, and the Giraffe House still in use was built in the 1830s.

Walking in the zoo today, one feels many shadows of the past: not just from the physical compound of Decimus Burton’s nineteenth-century architecture and grounds, but also from the historical legacy of imperialism. The zoo was the project of Sir Stamford Raffles, imperialist extraordinaire. His day job was subduing and plundering Java and Sumatra as a colonial agent for the East India Company. As a hobby, he amassed animals during his exotic adventures, and this menagerie became the Zoological Society’s founding collection.

Zoogoers looking at these penguins’ silhouettes might recall the shadowy legacy of captive animal display as a celebration of Victorian triumphalism, offering spectators a taste, an amuse-bouche, of the British Empire’s global conquests. The intent was to persuade the masses that they benefited somehow from the imperial enterprise – that is, “the white man’s burden,” achieving domination and ownership, imposing commercial, cultural, political, and ideological control upon all the world’s different regions and habitats and cultures. The proletariat’s payoff was simply being able to see all these geographically diverse and exotic creatures and bask in the prowess that facilitated the exhibition of such a splendid corpus of animals in the heart of London.

Are the animals actually there at all, or are we just watching shadow-puppets playing out the nostalgic fantasy of imperial control?

© Randy Malamud.

Zoo by Britta Jaschinski is published by Phaidon.

Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud (1/5)

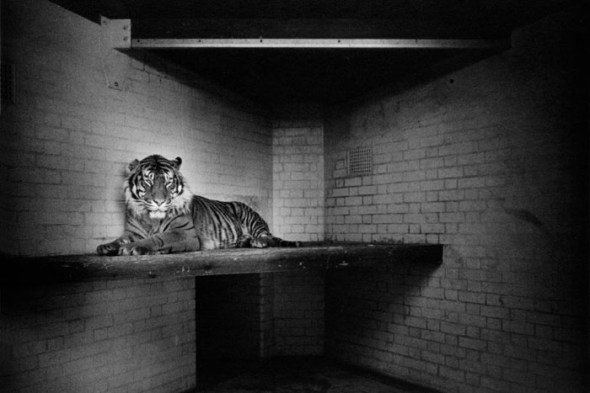

Posted: December 5, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Wildlife | Tags: Sumatran tiger 2 CommentsSumatran Tiger, Zoo Series, London Zoo 1993. © Britta Jaschinski.

Randy Malamud writes:

Britta Jaschinski’s portraits of animals show an insightful expression of the animal’s identity and individuality, an almost devout fascination with the animal’s spirit. But at the same time they resemble mugshots of trapped and unhappy creatures at their worst moments of suffering, caught and fixed in the harsh frame of the image (which is itself metaphorically another cage). They convey loneliness, alienation, displacement. Paradoxically, a single picture may evoke these disparate sensibilities at the same time, both an homage to the animal’s nobility and an angry protest at his constraints.

A photograph of a Sumatran tiger (except it isn’t a Sumatran tiger any longer; now it’s a London tiger) reveals pathos, injustice: the pain of an animal in captivity, The tiger is still, silent, stuck. A pervasive human geometry defines the space. If spectators can infer any sense of emotion or sentience from the creature depicted in a room of sterile white tile, it is resignation, defeat, anomie.

People have a propensity for gawking at subjugated otherness — for example in freak-shows or on reality television — as a way of reaffirming our own supremacy. In the nineteenth century Londoners used to go to Bedlam (St. Mary Bethlehem Hospital) to stare at the lunatics. For a penny one could peer into their cells and laugh at their antics, generally sexual or violent. Entry was free on the first Tuesday of the month. Visitors were permitted to bring long sticks to poke the inmates. In the year 1814, there were 96,000 such visits.

© Randy Malamud.

Zoo by Britta Jaschinski is published by Phaidon.