London Perceived. Text V.S. Pritchett, photos Evelyn Hofer (1/5)

Posted: July 25, 2011 Filed under: Clubs, Eating places, Literary London, London Types | Tags: Evelyn Hofer, Garrick Club, London Perceived, V.S. Pritchett 1 CommentHead waiter, Garrick Club, 1962. Photo © Estate of Evelyn Hofer

V.S. Pritchett writing in London Perceived*, 1962:

And what happens in square and pubs goes on in clubs, all the thousands of drinking clubs, the luncheon clubs, the dining clubs, the sporting clubs, the dance clubs, to the great clubs around Pall Mall and St. James’s. You are a Londoner, ergo you are a member. You are proposed and seconded; that done, you are among a few friends; you have your home from home. In none of these clubs is any utility of purpose frankly admitted. It is true that Bishops and Fellows of the Royal Society gather at the Atheneaeum; actors, publishers, and the law at the Garrick; the aristocracy and the top politicians at Boodle’s, White’s, or Brooks’s; that, following Stevenson and Kipling, a lot of bookish, professorial and civil wits are at the Savile, and professional eminences at the Reform, where Henry James had a bedroom with a spy hole cut in the door so that the servant could see whether the master was sleeping and refrain from disturbing him. (The hole is still there.)

Clubs change. London is made for males and its clubs for males who prefer armchairs to women. The great clubs are in difficulties. Their heyday was the Victorian age, when men did not go home early in the evenings; now at night they are empty of all but a few bachelors, sitting in the drying leather chairs. Some clubs have tried allowing ladies to dine in the evening, but the ladies, after the first riush of curiosity, in which they hoped to find out what happy vices their men were comfortably practising there, tend to be appalled by these mausoleums of inactive masculinity, even when they are elegant, and tend to be depressed by the gravy-coloured portraits on the walls. The architecture, gratifying to male self-esteem, does nothing for the sex, and the boredom that hangs like old cigar smoke in the air is a sad reminder of the most puzzling thing in the sex war: that men lie each other, rather as dogs like each other. The food is dull, but a point that the ladies overlook is that the wine is excellent and cheap.

How did this taste for clubs begin? Did it start with the witenagemot or the monasteries? Did it sprout from the guilds – for what are the Drapers’, the Fishmongers’, the Armourers’, the Watermens’, the Grocers’ companies, with their medieveal robes and seremonies, but medieval guilds turned into clubs for the Annual Dinner? The clubs start, as the whole of visible London does, except the Tower and Westminster Abbey, St. Bartholomew and the Elizabethan buildings in Staple Inn – the clubs start with the greatest of all london inventions: modern mercantile capitalism. They began with the coffee houses in the City. “We now use the word ‘club'”, Pepys wrote, “for a sodality in a tavern”. Lloyds was a coffee house, the place where one could read a paper and hear the news, and the more one sat about there, the more one heard. They were often started by servants – the most domineering of men – by the race of Jeeves, for the Woosters, the masters of the world; fashionable clubs like Boodle’s, Brooks’s, White’s take their names form the servants who founded them. The idea has the ease of Nature, and it is only in the nineteenth century, when industrial wealth came in, that clubs like the Public Schools, became outwardly pretentious and expensive.

* © 1962 and renewed 1990 by V.S. Pritchett. Used by permission of David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.

[Special thanks in assembling this week’s feature are due to: Jim McKinniss; Mark Giorgione of the Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California; Andreas Pauly at the Hofer Estate; and Carl Scarbrough at David Godine. D.S.]

38 Special. Photo & text: Tim Marshall (5/5)

Posted: July 15, 2011 Filed under: Transport | Tags: number 38, Tim Marshall, Walker Evans Comments Off on 38 Special. Photo & text: Tim Marshall (5/5)Angel. Photo © Tim Marshall.

Tim Marshall:

I started the ’38 Special’ bus project largely because the bus was always so overcrowded that rarely could you get a seat to read the paper. So, in order to fill the time, I began to take photographs during my journey to and from college. The whole of life’s rich tapestry unfurls on a bus and I soon extended the brief to observe the small dramas that occurred outside the bus as well. Although the real action often happens when I pass college and head towards China town and Piccadilly Circus, the main challenge had been documenting the journey from Essex Road to Central Saint Martin’s.

David Secombe:

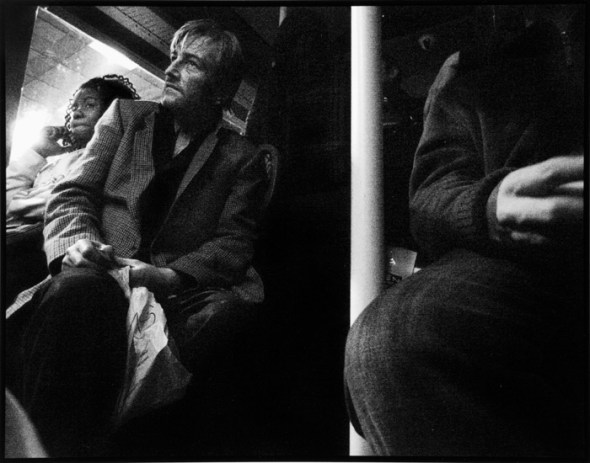

Between 1938 and 1941, the great Walker Evans took his (suitably disguised) camera on the New York subway and photographed unwitting passengers. The photo are sweet and revealing but don’t have that unflinching, forensic power that we associate with Evans at his best: the man who photographed the faces and homes of poor, Depression-era farmers with such eloquence and grace. Tim has cited Walker Evans’ 1930s photos of the New York subway as an influence, but unlike Evans, Tim Marshall was not trawling the public transit systems for material, he was keeping a visual diary as he travelled to work. When he photographs bored commuters stuck on a bus stranded by traffic, he is one of them. These days, a photographer taking his camera onto public transport risks exposure, ridicule, violence and possibly arrest. I don’t know what subterfuges Tim used in order to conjure up the images that make up his 38 Special project, but as the image reproduced above shows, it was worth it. We will run more of them later in the year.

38 Special. Photo Tim Marshall, text Travis Elborough (4/5)

Posted: July 14, 2011 Filed under: Transport | Tags: No. 38, Timothy Hadrian Marshall, Travis Elborough, Tysoe Street Comments Off on 38 Special. Photo Tim Marshall, text Travis Elborough (4/5)On board a 38, Tysoe Street, Islington. 2005. Photo © Tim Marshall.

From The Bus We Loved; London’s affair with the Routemaster* by Travis Elborough:

When I started writing this book I was living in Tufnell Park, in a flat bang opposite the tube. Hulking, over-sized overfed double-decker buses on route 134 to Archway drove past our kitchen window every hour of the day, creating a thrum and a hiss that was impossible to ignore. Around the corner, fractionally our of view and completely out of earshot, the 390 Routemasters ploughed back and forth to King’s Cross, in their own quietly efficient and self-effacing way. Most mornings I used to catch one down to the British library near St. Pancras, savouring the pleasures of the ride, before spending the day browsing self-published pamphlets on the Greenline service of the 1960s.

On my walk to the bus stop I’d usually see an elderly derelict, his hands always encased in oversized industrial rubber gloves, clinging on to the railings near the Spaghetti House restaurant on the corner of Fortress Road. Ahab on the slipstreams of the A1, his mornings were devoted to staring at the flows of traffic that passed before him. Usually a sage-like observer, indifferent to the sirens, beeping horns and screeching tyres, he would intermittently be roused into rage by particular vehicles. Refuse lorries caused him no end of dismay.

Later in the year I moved to Stoke Newington but a few weeks afterwards I had to return to the old flat to pick up some post. Coming out of the tube on a grey autumn afternoon, I found old rubber gloves was still there; this time howling like a banshee at a brand new double-decker on route 390. He sounded as if he was in pain, but then he’d always sounded that way. It’s easy, perhaps, to read too much into these things.

© Travis Elborough 2011

* Published by Granta.

38 Special. Photo: Tim Marshall, text Susan Grindley (3/5)

Posted: July 13, 2011 Filed under: Literary London, Transport 1 CommentExmouth Market, 2002. © Tim Marshall.

The Man in the Violet Polo Shirt by Susan Grindley

Like a mime-artist performing brain-surgery,

the man in the violet polo-shirt –

seeing that neither driver would back down and back up,

and after a final, ‘Why should I?’ from each –

coaxed the Vauxhall between the 277 and the steel cage

enclosing the road works.

At spitting-range there was another bout of shouting

but, from the bus, the street and the cars,

backed-up, hooting, in Frampton Park Road

and Well Street, we could see it was a win-win situation,

so when the man in the violet polo-shirt came back onto the bus,

some of us clapped.

[This poem first appeared in Rising magazine.]