Nights at the Opera. Photo David Secombe, text Edward Mirzoeff (1/5)

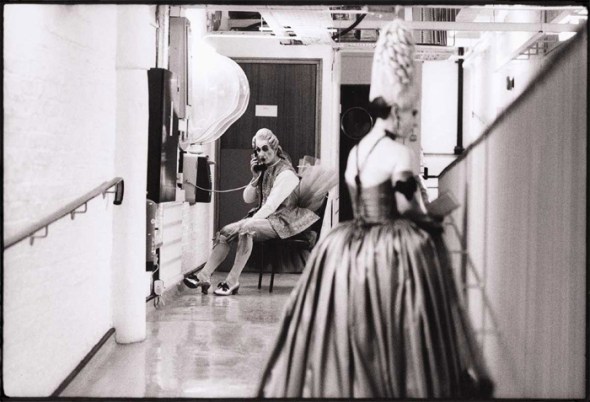

Posted: August 1, 2011 Filed under: Interiors, London Music, London on film, Theatrical London | Tags: royal opera house, The House, wig Comments Off on Nights at the Opera. Photo David Secombe, text Edward Mirzoeff (1/5)Backstage, Royal Opera House. Photo © David Secombe 1994.

Edward Mirzoeff writes:

The House was, in many ways, the definitive “fly-on the wall” television documentary series. The six episodes, shot in 1993 and 1994, went behind the scenes at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden to reveal the astonishing dedication, talent and sheer hard work put in by singers, dancers, technicians and craftspeople in decaying and unhelpful surroundings. It also revealed the equally astonishing conflicts, confusions and ineptitudes of some members of the management and some grandees on the Boards.

The television audience, and newspapers all over the world, were gripped by the saga from week to week. Some people took it as an allegory of the state of the nation. And after it was over, the series went on to win all the prizes. BAFTA, Banff Festival, Broadcasting Press Guild, International Emmy, Royal Philharmonic Society – The House cleaned up all the statuettes.

Just one puzzle remained. Despite the many awards, despite the publicity and controversy, the series was never shown again. In a culture of endless repeats of mediocre television programmes, such restraint by BBC Controllers was curious.

[Edward Mirzoeff was executive producer of The House for BBC Television.]

Days and Nights in W12. Photographs and text: Jack Robinson (1/4)

Posted: June 29, 2011 Filed under: Amusements, Interiors, London Types | Tags: CB Editions, massage parlour, Shepherd's Bush, W12 Comments Off on Days and Nights in W12. Photographs and text: Jack Robinson (1/4)Massage parlour: Askew Road, W12, 2010. Photo: © Jack Robinson.

From Days and Nights in W12* by Jack Robinson:

MASSAGE PARLOUR

Extras? You mean, as in ‘other services offered’? She runs through a menu of the day’s specials and when they say the prices seem a bit expensive she says so is philosophy, which is what she is studying, and it’s especially expensive for foreign students and why do they think she’s working here, for the fun of it? Some of them ask her what’s wrong with a bit of fun, missing the point completely. Some of them make a joke of it, asking how much for the meaning of life. (A lot, she says; more than you can afford, little man.) Some of them suggest she should be studying economics, or at least taking a joint degree, and point out that if she charged less she might get more takers. They have a point, she admits; but she is proud of her philosophy essays and her tutor says she has a natural gift and she knows what she’s worth.

© Jack Robinson 2011.

*CB Editions, 2010

Londei’s London Shops. Photo & text: John Londei (3/3)

Posted: June 9, 2011 Filed under: Interiors, Shops | Tags: John Londei, Shutting Up Shop, Small shops, tobacconist's Comments Off on Londei’s London Shops. Photo & text: John Londei (3/3)Tom Cornish, Tobacconist, 87 Clerkenwell Road, EC1. Photo © John Londei

John Londei writes:

This was the second photograph I took for my book Shutting Up Shop. The tobacconist sat across the road to my studio, two doors along from ‘Morrison’s’ the chemist, the shop that started the ball rolling.

In 1956 William Hadly was de-mobbed from National Service. “A friend got me a job here telling me: ‘You’ll only be number two’. In 1959, I ended up buying the business.”

Tom Cornish opened the shop over one hundred years ago. “I never met him. He went out of business in 1911. But I still keep the picture of him – our ‘founder’ – above the clock. It shows the business has some standing.”

The shop had remained unchanged since William took over, the corner wooden phone kiosk an echo of the days when most people didn’t own a telephone. “You’d be surprised how many people comment on it. Only tobacco, I sell only tobacco, nothing else! Not even chewing gum. Every morning I’m up at 5.20, and open the shop at 7 o’clock. I shut at five in the evening. We always make sure we are in bed by 9.30. The biggest change for me was when VAT started in 1973. Most nights I do the books. The VAT has given me so much extra work.”

George Fieldwich, who had worked at a local pub, joined the shop at the age of seventy-one. William’s wife, Erna, was Austrian, and used to be a language teacher. “I enjoy the foreigners’ surprise when I speak to them in their own tongue. I am a non-smoker. I would have preferred to run a bookshop.”

William always seemed to have his pipe permanently clenched between his teeth; in fact I can’t remember ever seeing him without it. “I go all round the jars and try them all out. People come from miles around for this stuff. Once you’ve got a customer, you’ve got them forever. That’s why we don’t change the name of the shop, because it was famous.”

Erna also saw no reason to change things. “See that ‘Senior Service’ lady on the wall… We could have sold her a hundred times over. We have had many offers for her. But we always refuse.”

© John Londei 2011

John Londei’s book Shutting Up Shop: the decline of the traditional small shop is published by Dewi Lewis.

Point of Interest. Photos Peter Marlow (3/3)

Posted: June 3, 2011 Filed under: Interiors | Tags: Joel Meyerowitz, Magnum, Martin Parr, Peter Marlow, Wapping Project Bakside, William Egglestone Comments Off on Point of Interest. Photos Peter Marlow (3/3)Gainsborough Studios, Islington, 2000. Photo © Peter Marlow (from Point of Interest, courtesy of the photographer and The Wapping Project Bankside*).

David Secombe writes:

Since William Egglestone’s pioneering use of colour print film as an artistic medium in the 1970s, an entirely new photographic aesthetic has developed. Egglestone built upon the achievements of an earlier school of American street photographers – Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander – by substituting colour in place of his forebears’ graphic black and white. Although Joel Meyerowitz and Joel Sternfeld were exploring similar territory at the same time, it was Egglestone’s 1976 show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art that made a landmark in the acceptance of colour photography as a serious art form.

Looking back, it is hard to comprehend the astonishment – even outrage – of the art establishment towards Egglestone’s super-saturated, over-sized prints of quotidian yet disquieting scenes of his native Tennessee. Egglestone’s embrace of what became known as the ‘snapshot aesthetic’ – unnerving observations of the mundane familiar to anyone who has ever been surprised by an anomalous photo amidst their family snaps – was revolutionary. The cool contemplation of unremarkable scenes was a long way from the approach of that earlier champion of colour photography, Ernst Haas, whose work echoed the Abstract Expressionists and who often worked for National Geographic: Egglestone’s pictures didn’t belong there.

Egglestone’s influence has been immense. The intensity of his treatment of colour found a UK disciple in Martin Parr, who abandoned his earlier, understated black and white exploration of the English scene (clearly under the influence of Tony Ray-Jones) sometime in the mid-1980s, in favour of a picaresque and brightly-coloured journey across Britain and beyond. In the 1990s many notable reportage photographers who had specialised in black and white followed the trend and abandoned their earlier practice in favour of a move towards colour, often preferring medium format to 35mm. At the same time, advances in technology made it easier to reproduce images from colour prints, obviating the frustrations and limitations of colour transparency film. And the rise of a new breed of art/fashion photographers – notably Juergen Teller and Wolfgang Tillmans – promoted a certain kind of affectless, abstracted snapshot chic.

The photo by Peter Marlow reproduced above represents the photographer’s move away from his earlier black and white photojournalism towards a more personal way of seeing the world. It is perhaps fair to say that whilst Marlow could have taken an image like this at any stage in his distinguished 30+ year career, it is the widespread acceptance of the post-Egglestone aesthetic that has emancipated this type of picture from the bottom drawer. The photo – taken on film – dates from 2000; two years later, sales of digital cameras outsold their film counterparts for the first time. Future historians may come to judge an image like this as belonging to a certain period in time – a period that began around 1970, and ended with the maturity of digital photo technology. In the digital age, the medium itself encourages promiscuity, along with its concomitant disposability: the temptation to delete an anomalous image to make space on an SD card is all too real. It requires real commitment to record the day-to-day strangeness of the world on a commodity as valuable as film.

… for The London Column. © David Secombe 2011.

* Point of Interest is showing at The Wapping Project Bankside, London SE1, until 2 July 2011.