Drinker’s London. Photos Paul Barkshire, text David Secombe. (2/5)

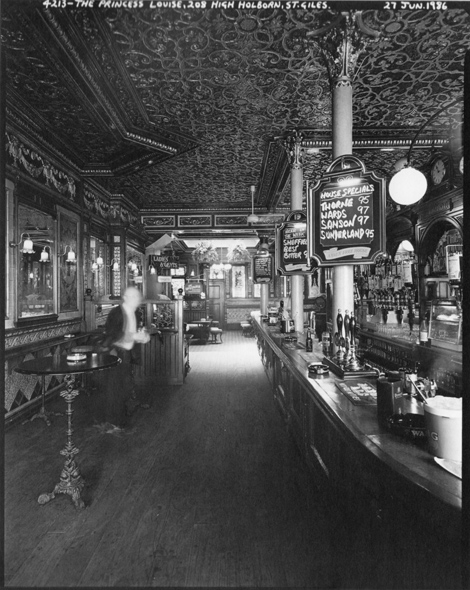

Posted: October 19, 2011 Filed under: Artistic London, Bohemian London, Literary London, Pubs | Tags: Ezra Pound, London bohemia, Sam Smiths pubs, The Princess Louise, The Rhymers Club, W.B. Yeats Comments Off on Drinker’s London. Photos Paul Barkshire, text David Secombe. (2/5)Princess Louise, Holborn,1986. Photo © Paul Barkshire.

The Princess Louise is one of those carefully time-locked London pubs where one is invited to experience a idealised ‘heritage’ drinking experience: the Louise escaped post-war redevelopment and refurbishment and has survived into the 21st century as an authentically preserved/recreated Victorian boozer. At time of writing, the only beer on offer in the Louise is Sam Smiths, a rather dense, tawny ale brewed in Yorkshire; its main appeal is that it is remarkably cheap, but it is perhaps no coincidence that Sam Smiths currently lay claim to several other historic London pubs: these include the legendary Fitzrovia hangouts The Wheatsheaf and The Fitzroy Tavern, both much-frequented by the likes of Augustus John, Dylan Thomas, George Orwell, etc. – and also The Cheshire Cheese on Fleet Street, known to writers from Samuel Johnson (allegedly) and Charles Dickens up to Oscar Wilde, W.B. Yeats and Ezra Pound. (The Cheese was where Wilde came to hear John Gray, the model for Dorian Gray, read his poems, and where Pound demonstrated his impeccable Modernist credentials by eating two red tulips during a recital by Yeats.)

Since Paul Barkshire’s photo was taken in the 80s, the Princess Louise has had another make-over, reinstating ‘authentic’ Victorian mahogany & etched glass partitions, the original purpose of which was to divide up the patrons according to class and occupation. The end result is undoubtedly charming, and Sam Smiths should be congratulated for the sensitivity of their management of these historic pubs. The problem is that the loving restoration reinforces the sense of theme park, that creep of ‘Heritage’ (a tainted word if ever there was one) which imprisons London. The ghosts of the past are marooned amongst the tourists, and the centre of town is closed off to the truly louche and experimental. The Fitzroy Tavern and the Wheatsheaf can never be what they were in the 1920s and 40s; and where would The Rhymers’ Club, that austere flower of the Aesthetic movement which met at the Cheshire Cheese from the 1890s up to 1914, attracting Wilde, Yeats, Dowson, Pound, etc., meet today? A loft in Peckham or Dalston, probably. D.S.

… for The London Column.

Homer Sykes: Britain in the 1980s. Text by Various. (3/5)

Posted: September 21, 2011 Filed under: Amusements, Pubs | Tags: Gap Band, Homer Sykes, Hues Corporation, Oops Upside Your Head, Rowing Boat Dance 1 Comment‘Oops!’ (Rowing Boat Song), Hen Night, South London pub, circa 1980. © Homer Sykes/Photoshelter.

From Do You Remember? Forums

What was that dance called?

Posted by Bruce, 05/04/2005:

I remember a dance where you all sat in a line on the floor with your legs astride the person in front and then swayed from side to side and stuff. What was that dance called and what song was it meant to go with?

Posted by Precious Jewels, 08/04/2005:

It was for ‘Oops Upside Your Head’ by the Gap Band…Sweet reminiscing of discos growing up! Did it have a name for the actual dance?!

Posted by lionlevy, 19/04/2005:

Assorted aunties used to refer to it as “that boat song…” Very popular with aged relatives for some reason, despite their assorted dodgy arthritis & rheumatism doing its best to hinder them.

Posted by scallycapsforever, 09/08/2005:

Yeah the row boat song. A classic at family dos the length and breadth of the country it was also hilariously lampooned on ‘Men Behaving Badly’ to ‘Sailing’ by Rod Stewart.

Posted by Zen Master, 30/04/2005:

Not sure of the name of the dance but the song was a group called Forest, I will find the title later, was played at a birthday evening or event. Great fun all innocent……fun.

Posted by Clive Henry Jones, 27/06/2005:

Yeah, Forrest did “Rock the Boat” but it was a cover of The Hues Corporation’s original. This track was not a dedicated dance track, though, as “Oops upside your head” was (Rowing boat dance). As a DJ, I stll play “Oops” at mixed aged parties because:

a. It’s a good track which fills the dancefloor.

b. You get to look up women’s skirts as they get down (and up) – all innocent, though and I dare you to try to not look and see who’s wearing suspenders & who’s not.

c. You usually gety some saddo walking up and down the line of “rowers” whipping them with his tie.

Posted by SG1973, 26/05/2007:

Saw an interview on tv with the Gap Band and they said when they first came to England to do TOTP they couldn’t understand why everyone sat on the floor swaying from side to side. They’d never seen it done before. Must be an English eccentricity thing.

Homer Sykes: Britain in the 1980s. Text by Charles Jennings. (2/5)

Posted: September 20, 2011 Filed under: Class, Pubs | Tags: Charles Jennings, Homer Sykes, People like Us, sloane rangers, The Queen Mother 1 CommentSloane Rangers, Kensington, 1983. © Homer Sykes/Photoshelter.

Society Wedding by Charles Jennings:

‘The Boltons, yes. And I mean, the Queen Mother’s actually been there, to dinner, apparently.’

‘Really?‘

‘But apparently she didn’t sign the visitors’ book.’

‘Well, she wouldn’t would she?’

‘So of course, James’ – the boyfriend – ‘had to volunteer first, so they gave him a box of watercolours and a brush. And he spent ages trying to get the watercolours to go on the brush, but he’d forgotten that he needed some water first.’

‘He’s so sweet, James, so funny.’

‘Thing is, Emma had James’ Jack Russell as a bridesmaid –‘

‘As in a dog?’

‘So sweet!’

‘Emma phoned, the honeymoon was fab, wants to meet up –‘

‘Istanbul? I know that city, actually. Went with Simon and Gemma and Charlie last summer. Charlie’s so funny, he stood outside that big mosque and – ’

‘Why couldn’t she make it tonight?’

‘Dinner with James’ grandmother. She’s ninety and lives in a tiny flat on Trafalgar Square.’

‘I didn’t know anyone lived there!’

‘So sweet!’

… for The London Column. © Charles Jennings 2011.

London Perceived. Text: V.S. Pritchett, photos Evelyn Hofer (2/5)

Posted: July 26, 2011 Filed under: London Types, Pubs | Tags: Evelyn Hofer, London Perceived, The Salisbury, V.S. Pritchett Comments Off on London Perceived. Text: V.S. Pritchett, photos Evelyn Hofer (2/5)The Salisbury, St. Martin’s Lane, 1962. © Estate of Evelyn Hofer.

V.S. Pritchett, writing in London Perceived*, 1962:

The square is our characteristic alternative to the grande place or the piazza. There are no central places, foreigners complain, where “Londoners meet” or stroll along together to pass the time of day. The answer to that is, first, that Lononders do not meet, do not gather, and reject the peculiar notion that people like “running across each other” in public places. They emphatically do not. We are full of clubs, pubs, cliques, coteries, sets, although the influence of mass life are changing us so that even the London public house is becoming public. But most pubs are still divided into bars, screened and provided with quiet mahogany corners where the like-minded can protect themselves against those of different mind. And – one must admit – with different purses.

Clearly, between the saloon bar and the public bar there is, or was, a class division; nowadays, the public bar is where men play darts. In the public bar, there being the thirsty tradition of manual work, you drink your beer by the pint; in the saloon, in the private, you drink it in half-pints; occasionally there is a ladies’ bar, and there ladies – always in need of fortifying, for they have been on their “poor feet” – commonly order stout or “take” a little gin in a refined medicinal way. The pubs catering for the Irish are rather different; the Irish like to swarm in public melancholy, their ideal being, I suppose, a tiled bar resembling a public lavatory a mile long, and with barmen who, as they draw your draught stout, keep an eye on you, show their muscles, and tacitly offer to throw you out by collar and shirt-tail. This is not the London English fashion, which is livelier, yet more judicious, sentimental and moralizing. The London publican cultivates a note of moneyed despondency and the art of avoiding “argument” by discussing the weather. One foggy, snowy morning in a pub in Lamb’s Conduit Street, near Gray’s Inn, I hear a customer mention the cold and the snow, and, in doing this, he was simply repeating what every customer had said as he came in.

“Couple of cases of sunstroke in the Feobal’s Road, I hear” said the poker-faced old Weller behind the bar – belonging to that generation of Cockneys who pronounced a “th” as an “f” and were averse to a final “d”. He spoke in the gravelly voice of one about to “cut his bloody froat”.

There are pubs where the same people always meet, where they tell the same stories, where they glance up at the changing London sky and sink into mournful happiness or fatten and redden with natural bawdy – I do not mean dirty – stories but with licence of their own invention. One is reminded that this is the city of the riper passages of Shakespeare and the sexy London papers. London is not puritan; it is respectable – quite another matter. Behind the respectability is the sentimental and fleshly riot. If they can be sure that they are among “a few pals, the male and female Londoners like to abandon themselves. The whited sepulchres turn rosy, the tongues wag, even raucously sing, and the ladies come out with quiet remarks that are surprising. There is a touch of “Knees up, Mother Brown” in all of them; in London, Eros is a shade hearty, and what is elsewhere called passion, in London is called being “friendly”. Friendliness is, of course, double-edged , for it suggests that some would-be friends must be kept out. A little scene I once observed at the bar of the Edinburgh Castle, in Camden Town – the Bob Cratchit country – goes to the heart of this aspect of London manners. A middle-aged couple were having a friendly talk, and an old man, suffering from city loneliness, occasionally “passed a remark” – always an offence – hoping to join in. The lady reached for her large handbag – an emblem of respectability – and took out a pound note – a sign of grandeur – put it on the counter and called to te old man in a “friendly” voice:

“Have a drink. Say ‘No thank you’; I always say ‘No, thank you’ when a stranger offers me a drink.”

And she put her pound note back in her bag, closed it with a slow snap, and, swollen with savoir-faire in the art of “friendliness” she resumed her private conversation. The Londoner know how to finish things without being, as the saying is, “nasty”. One had witnessed a death, of course.

* © 1962 and renewed 1990 by V.S. Pritchett. Used by permission of David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.

[Special thanks in assembling this week’s feature are due to: Jim McKinniss; Mark Giorgione of the Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California; Andreas Pauly at the Hofer Estate; and Carl Scarbrough at David Godine.D.S.]