Swansong.

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones 6 Comments Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

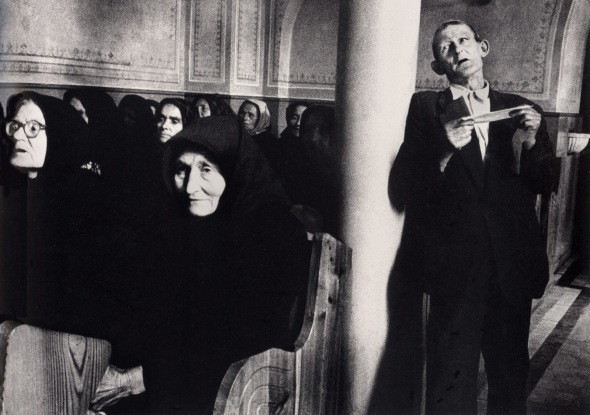

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

Before the Blue Wall. Photo: Homer Sykes, text: Katy Evans-Bush. (4/4)

Posted: July 13, 2012 Filed under: Vanishings, Wildlife | Tags: Homer Sykes, Katy Evans-Bush, LeaValley, Olympic legacy, Olympic site, Walthamstow Marshes Comments Off on Before the Blue Wall. Photo: Homer Sykes, text: Katy Evans-Bush. (4/4)

Anglers on the river Lea. © Homer Sykes 2006.

Katy Evans-Bush:

These two men were fishing in this spot in 2006. For all we know, they’d sat there every available Saturday since they were ten. But we know they’re not sitting there now. It’s in the past – that is, it’s in the Olympic ‘Park’.

The website for the adjacent Walthamstow Marshes says: ‘The reserve is one of the few remaining pieces of London’s once widespread river valley grasslands, and a space to treasure for many reasons!’

The Wikipedia page for the Lower Lea Valley, which means roughly the same place, says ‘the Olympic Games… will provide a legacy of facilities for this currently run-down area. There are plans to redevelop all the derelict and underutilised [sic] parts of the valley, which will take until 2020 or beyond’.

… for The London Column.

A selection of pictures from Before the Blue Wall, Homer Sykes’s project documenting the Lea Valley prior to the Olympic redevelopment, may be seen at the Green Lens Gallery (4a Atterbury Road, London N4 1SF) until the 25th of July. Homer’s website is here.

Before the Blue Wall. Photo: Homer Sykes, text: Tim Wells (3/4)

Posted: July 12, 2012 Filed under: Transport, Vanishings | Tags: greasy spoon, Homer Sykes, Joe Public, Olympic Park, Tim Wells Comments Off on Before the Blue Wall. Photo: Homer Sykes, text: Tim Wells (3/4)Transport cafe, Hackney Marshes. © Homer Sykes 2006.

My Bitch Up

Burning Geronimo through the East End, the motor skittish at jump, stop, start.

Music blasting out the windows, slapping Joe Public in the face as we roar by.

Tossing the used notes behind us, dirty knees and carpet burn noses.

Each staccato burst spent, surly, and spittin’ in the eye of every pocket money massive.

On Commercial Road some City boy lone ranger races us red light to red light,

every green a pistol shot.

At Limehouse John John faces him and mouths, “Ours is stolen.”

The silence: single mum heavy. Someone drops the sprog.

© Tim Wells.

A selection of pictures from Before the Blue Wall, Homer Sykes’s project documenting the Lea Valley prior to the Olympic redevelopment, may be seen at the Green Lens Gallery (4a Atterbury Road, London N4 1SF) until the 25th of July. Homer’s website is here.

Before the Blue Wall. Photos: Homer Sykes, text: David Secombe. (1/4)

Posted: July 10, 2012 Filed under: Vanishings | Tags: 2012 Olympics, Before the Blue Wall, Homer Sykes 1 Comment2012 Olympic site perimeter fence, Lea Valley. © Homer Sykes 2007.

David Secombe:

This week we are featuring a few of Homer Sykes’s images of the Lea Valley immediately prior to its transformation into the 2012 Olympic ‘zone’.

In 2006, searching to record for posterity a neglected moment in time, Homer made it his personal mission to explore the future site of the Olympic Park – soon to be encircled by a barrage of hype, and by the anonymous and blandly forbidding Blue Wall. Indeed, the blue wall shown in the picture above was the most visible token of the impending funfair – and it served as an unwittingly potent symbol of loss. In these images, Homer shows what was there before: a curious mix of wildflower meadows alongside neglected sports fields, semi-derelict 19th century industrial buildings sprawling cheek by jowl with unidentifiable dwellings cloaked in ivy – an almost rural atmosphere emanating, against all odds, from the urban blight.

Cities are organic entities, and London has, traditionally, ebbed and flowed as entire districts go in and out of fashion, or are repurposed in the light of changing circumstances. Elsewhere on The London Column, we have railed against the imposition of corporately-sponsored ‘Regeneration’ schemes upon areas that have developed their own post-industrial ecosystems: those intriguing backwaters where town becomes wilderness. Sadly, these romantic urban oases are too easily seen tabula rasa for this or that grand scheme – which are invariably sold in as a boon to the local community. But one only has to look at the dislocated, dystopian landscape of ‘North Greenwich’ to see what happens to an event site after the event has gone.

Homer will be presenting a slideshow of images from Before the Blue Wall at the Green Lens Gallery, 4a Atterbury Road, London N4 1SF, on Wednesday 11 July between 6 and 9 pm. Homer’s website is here.