London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (1/5)

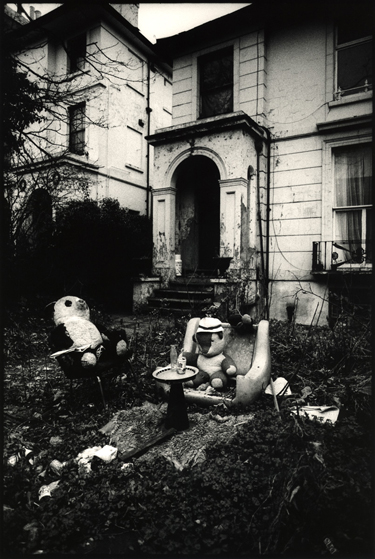

Posted: July 2, 2012 Filed under: Dereliction, Literary London, Vanishings, Wildlife | Tags: Arthur Machen, Camden, Holloway, London Gothic, Peter Ackroyd, tea party Comments Off on London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (1/5)Camden Road. © David Secombe 1987.

From London The Biography by Peter Ackroyd, 2000:

Whole areas can in their turn seem woeful or haunted. Arthur Machen had a strange fascination with the streets north of Gray’s Inn Road – Frederick Street, Percy Street, Lloyd Baker Square – and those in which Camden Town melts into Holloway. They are not grand or imposing; nor are they squalid or desolate. Instead they seem to contain the grey soul of London, that slightly smoky and dingy quality which has hovered over the city for many hundreds of years. He observed ‘those worn and hallowed doorsteps’, even more worn and hallowed now, and ‘I see them signed with tears and desires, agony and lamentations’. London has always been the abode of strange and solitary people who close their doors upon their own secrets in the middle of the populous city; it has always been the home of ‘lodgings’, where the shabby and the transient can find a small room with a stained table and a narrow bed.

David Secombe:

In the midst of our jingoistic Olympic summer, I thought it might refreshing to explore the aspect of London so eloquently evoked by Peter Ackroyd in the passage above. A city of silent yet inhabited houses, anonymous windswept streets, overgrown front lawns, strange objects on the back seats of abandoned cars, forbidding municipal playgrounds, etc. (This is essentially the same territory explored by Geoffrey Fletcher in The London Nobody Knows, and as the last series on The London Column was a revisiting of Fletcher’s book, this one may be seen as a continuation of the same theme.) ‘London Gothic’ is becoming increasingly rare; most of the streets that Arthur Machen thought of as woeful are now exemplars of prosperous gentrification. London is a cleaner, neater place: even King’s Cross is a landscaped zone now. The photo above was taken a quarter of a century ago, and Holloway has come up in the world since then. The specific, shabby London charm that Machen and Ackroyd describe may still be found, but one has to look harder. As a small boy visiting the city from the suburbs, I was amazed by the soft enveloping greyness which made the occasional bursts of colour all the more striking. That quiet visual texture is vanishing, when even municipal housing wears screaming day-glo colours, as 1960s & 70s blocks are clad in blue, yellow, or turquoise panels. London wears its dread in brighter shades these days.

… for The London Column.

Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, texts: Joanna Blachnio & Tim Marshall (4/4)

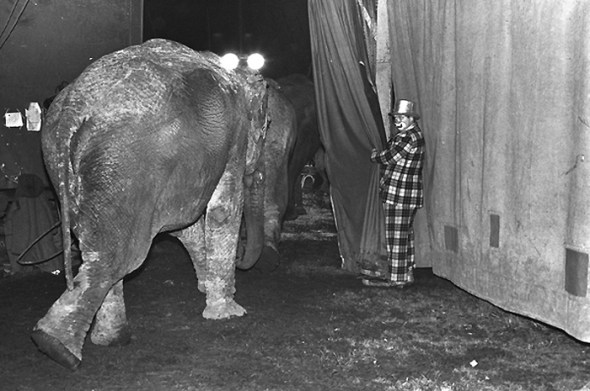

Posted: May 11, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Performers, Wildlife | Tags: Chunee, circus elephant, Clapham Common, clowns, Exeter Change, Joanna Blachnio, Julius Caesar, mad elephant, Royal Menagerie, Sir Robert Fossett's Circus, Tim Marshall Comments Off on Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, texts: Joanna Blachnio & Tim Marshall (4/4)Sir Robert Fosset’s Circus. © Tim Marshall 1984.

Joanna Blachnio writes:

Elephants in London have a long history. Tradition has it that Julius Caesar used a war elephant during his invasion of Britannia; he and his forces pitched camp not far from modern-day Bromley, so this un-named animal might be said to be the first pachyderm to impress suburban Londoners. In the 13th century, there was an African elephant amongst the Royal Menagerie which resided at the Tower of London – a gift from Louis IX of France. Plus, there is the elephant at the Elephant and Castle – although that area got its name from an 18th century coaching inn that stood in the vicinity.

One of the most poignant stories in the bestiary of London was that of Chunee, the mad elephant of Covent Garden. This sad creature arrived in Britain from India in 1809 as a theatrical and, later circus, animal, becoming one of the city’s attractions for almost two decades: even Lord Byron took note of his dexterity and good manners. He spent his dotage in the fabled menagerie at Exeter Change in The Strand, increasingly tormented by loneliness (there was no mate to help him while the time away) and a bad tusk. In February 1826, during his weekly parade down the Strand, Chunee rebelled against his captivity and went berserk, trampling one of his keepers in his rage. His temper did not subside and a death sentence was passed. The convict, however, clung on to life with the strength proportional to his body mass – almost seven tons. When they tried poisoning his food, Chunee was having none of that, and would not touch it. A troop of soldiers were sent for, yet even the fusillade from their muskets failed to kill the elephant, whose moans allegedly caused more distress than the sound of gunfire. Finally, one of his keepers ended his agony with a sword.

The elephants in Tim Marshall’s photograph are remote from the romance and pathos surrounding the death of their famous London ancestor. An impassive clown holding the curtain aside for their entrance, they take the stage with the weary docility of ageing pros. Their thick skin seems whitewashed in the glare of the stage lights. The last elephant to take to the ring can probably only sense what we are able to see: how much space there is in his wake.

Tim Marshall writes:

These photographs where taken in Easter 1984. At that time I was a student at Central St Martins School of Art making a life changing decision to stop illustrating with a pen and to start doing it with a camera.

I spent about four days photographing Sir Robert Fosset’s Circus. I remember going to Clapham Common at 8.00 in the morning, and before the circus site was in view hearing tigers roaring and elephants trumpeting, which was very surreal in central London. I photographed the tent being put up and only realized later that, everybody worked as a team and very hard. The tiger trainer helped put up the tent, starlets of the trapeze would, after finishing their acts, sell candy floss. Clowns empted bins. The clown Nelo, was not actually that funny and quite sad. Children would laugh at him rather than with him. He was a clown whose personal life seemed to be in complete disarray. But he wanted to be loved and make people happy.

After the show, I remember that certain pubs had a ‘no travellers‘ policy, so the people from the circus were refused entrance; and in the pubs they did manage to get into, they were only allowed in to the public bar rather than the lounge.

… for The London Column. © Joanna Blachnio, © Tim Marshall, 2012.

Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, text: David Secombe. (2/4)

Posted: May 9, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Entertainment, Performers, Wildlife | Tags: 'I am Grock', Bruce Davidson, Clapham Common, clowns, Pagliacci, Tim Marshall, Waiting for Godot Comments Off on Clapham Common Clowns. Photo: Tim Marshall, text: David Secombe. (2/4)Sir Robert Fosset’s Circus. © Tim Marshall 1984.

From The Greatest Show on Earth, director: Cecil B. DeMille, 1952:

BUTTONS’ MOTHER: They’ve been around again, asking questions

BUTTONS: I know Mother. They’ll never find me, behind this nose.

From Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo, 1892:

Bah! Sei tu forse un uom? Tu se’ Pagliaccio!

(Bah! Are you not a man?

You are a clown!)

David Secombe writes:

Clowns always make good subjects for photographers – the ‘tragic’ ones, that is, the sad clowns of popular cliché: gentle misfits of the travelling show, forever on the move, ageing into a fragile future. ‘I am Grock’ – that sort of thing. The quintessential clown photo remains Bruce Davidson’s unforgettable image of a dwarf clown in a bleak field somewhere in America. After Waiting for Godot, this image has become a different sort of cliché, foregrounding a forbiddingly grim-faced little clown against a drab urban wasteland. It’s a clown out of Beckett, a vertically-challenged Pagliacci for a nuclear world.

Tim Marshall’s clowns are a little more nuanced; for a start, they are full-size, but the gentleman who features in three out of the four pictures in this week’s series has impeccably tragic eyes – like a refugee from a silent film, we feel we know this clown’s backstory: the unfaithful wife, the vanished child, the dying mother … but it’s all conjecture, based on our cultural preconceptions and his amazing face. In a theatre or a circus tent we aren’t guaranteed a close look at the performers’ eyes – but in Tim’s portraits this gent becomes an archetype, as timeless and monumental as Nadar’s study of that ur-clown, Debureau, inspiration for the greatest film about the theatre (perhaps the greatest film about anything anywhere) Les Enfants du Paradis. We don’t have to know what this clown was like as a performer, we don’t need to see him working a Bank Holiday crowd (“the smell of wet knickers and oranges”) to decide whether or not he was any good: Tim’s picture immortalises him as one of the greats. He has the look of tragedy all about him.

… for The London Column.

Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (5/5)

Posted: December 9, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Wildlife 2 CommentsLar Gibbon, Zoo Series, London 1992. © Britta Jaschinski.

Randy Malamud writes:

An otherworldly darkness permeates Jaschinski’s work, a troubling philosophical depth that touches both the animal inside the frame and the human spectator who is outside looking at the creature. A sense of uncertainty resonates in her photography—uncertainty about the animal’s context, the animal’s sentience, the animal’s feelings. This sense of the unknown challenges the human audience’s habitual expectations of omniscient insight with regard to other animals.

I believe that it is wrong for us to see the monkey in the way we are seeing it, in a zoo, or even in a photograph from a zoo, and yet it is at the same time mesmerizing. Is this lar gibbon as fascinated by his spectators as we are of him? What does he think of us? We cannot know. The energy that Jaschinski’s image conveys is at the same time profound and profane. The longer we regard this gibbon, if we learn anything, it is how much we cannot know.

Our relationship with non-human animals is rich, intricate, and troubled. People are fascinated by animals, and respond to them in ways that are at times full of homage and awe, and at other times oppressive and perverse. We are prone to appreciate, or to fetishize, animals in isolation as discretely framed specimens (in a zoo, or as a pet, or a meal, or a toy) distanced from their groups, alienated from their contexts. But still they are there, all around us.

What is wrong here? What is missing? Where is the viewer situated in relation to the subject? What is the connection between imagining and exploiting animals? What has the photographic aesthetic done – and what have we done – to capture, and to betray, these creatures? What are these animals doing as we look at the sliver of their existence that is frozen and framed in the moment of each photograph? What kinds of movements, instinctual urges, behavioral patterns are suggested in the picture? And more to the point, what sorts of movements, instincts, and behaviors are suppressed in these images? A large “negative text” pervades Jaschinski’s photography. We are asked to see many things – habitat, activities – that are not there; we are confronted with their absence.

© Randy Malamud.

Zoo by Britta Jaschinski is published by Phaidon.