Recessional.

Posted: March 10, 2014 Filed under: Catastrophes, Class, Conspiracies, Corridors of Power, Housing, London scandals, London Types | Tags: banking crisis, CB Editions, filthy rich, housing crisis, Jack Robinson, Mayfair squatters Comments Off on Recessional.Jack Robinson:

This is my father driving in the 1940s, before I was born.

He left school at fourteen to work in an iron foundry his own father had helped establish; he eventually became joint managing director. We had a comfortable life without my mother having to work; single-income households were common then. He liked cars: I remember waiting at the front-room window one afternoon, when I was four or five years old, to see him arrive home in a brand-new olive-green Riley. Fifty years on from pressing my face against that window, I know that at no time has my own income been sufficient to raise a family in similar comfort, nor will I ever own a brand-new car; and my children will, if they go to college, be already mired in debt before they even begin to earn their own money.

The ignorance of the experts concerning the financial products they were using our money to buy is hardly new. James Buchan, in the late 1980s: ‘In London and New York I met people who invested fortunes in financial enterprises they simply could not describe or explain. No doubt quite soon, a bank would discover it had lost its capital in those obscure speculations; other banks would fail in sympathy . . .’ The politicians were even more ignorant. It’s as if for years we’ve been going with our tummy-aches to doctors who can’t tell the difference between a blister and a cancerous tumour. No wonder we’re ill.

The derivatives market conjured into existence in the 1990s was a virtual world, enabling speculation not in real assets but in the risk of speculation itself. It is addictive: the rush, the buzz, the winning streak. The opposite of which is the losing nose-dive – lose your job and you’re well on your way to losing your (real) house, marriage, health and dog.

An investment banker, quoted in the Standard: ‘In most cases they know their wives despise them for enslaving their lives to money, and they know that the moment they lose their job their wives will walk and take the kids, and their £3 million home, and divorce them.’ A lonely-hearts ad, placed on a literary website at the time the axe started to chop: ‘Ex-banker, 33 . . . Seeking woman not interested in money, fast cars, champagne, holidays, fleecing innocent hard-working gullible twats, whilst telling them you love them. Bitch.’

The above house in Mayfair, London, was squatted in January 2009 by a group that offered free workshops on welding, yurt-building, bookbinding, song-writing and de-schooling society. Hundreds of buildings are squatted; what made the press interested in this one was the stark disparity between the poshness of the building (alleged to be worth £22.5 million) and the presumed poverty of the squatters.

Bookbinding and yurt-building won’t change the world for the better overnight, but nor will sending out 400,000 repossession orders (Centre for Policy Studies estimate, February 2009) to households that have lost jobs and can’t keep up the mortgage payments.

I had a dream in which I punched the keys to withdraw money from a cash machine and it paid out in cowrie shells, rattling down a metal chute into the canvas bag I’d thoughtfully brought with me. As I walked to the supermarket the shells clacked satisfyingly in the bag by my side – I felt rich, rich. And then I woke up and went to my real bank and there was nothing there for me at all, they’d completely run out of money. Not a bean.

Ou sont les magasins d’antan? As well as the big ones, the small ones too. The place at the end of the road where I used to get my shoes re-heeled – where did that go? The café with over-priced food but a garden at the back where I could smoke? The minicab office in the next street? With the deadpan Somali driver who’d stop the car and get out and look up at the sky: he said he navigated by the stars, and I never knew whether he was taking the piss. Even with no office to return to, I hope that somewhere he’s still driving. There are very few recession-proof businesses; here is one of them.

The intensive factory farming of money makes it prone to many diseases, some of which can be transmitted to humans. There are government regulations concerning the application of biotechnology to the breeding of money, and there are also ways around them.In the last fifty years that part of the human brain dedicated to devising ways of getting money away from others and into your own hands has increased in size by 4 per cent.

He fell down the stairs. He slipped on the ice. He was coming home from work on Friday night when he got mugged – they took his money, his cards, his identity papers. They flung back his wallet, empty except for the photo of his kids – his kids to whom he’ll say, on Saturday morning, that he fell down the stairs, that he slipped on the ice

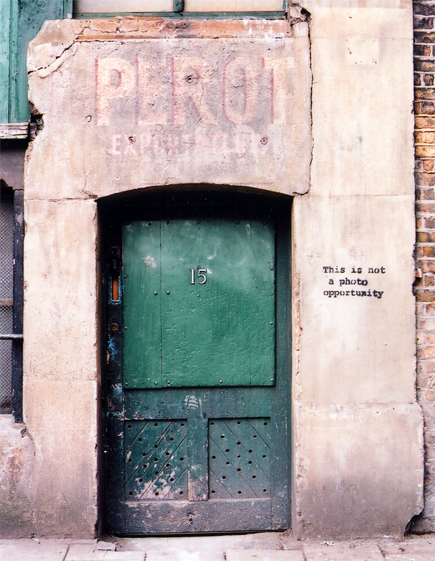

Behind this door – which is in a yard in the City of London – is the secret meeting place of a group of underground bankers. (There’s no external handle; you have to whisper the password through the grille on the right.) This group is deeply suspect: they buy books and music, not yachts and ski chalets, and their vocabulary extends beyond that of company reports. They are regarded by the rest of the banking world as heretics – because the whole point of being a banker is to speak in clichés, to have a single-track mind, to buy only the most predictable goods: that way they remain anonymous, almost invisible, and are left alone to get on with their thing.

God is dead (so can’t bail us out). Or couldn’t afford the heating bills for a place this big, or had had it up to here with the regular early-hours racket outside the lap-dancing club at the end of the street. Whatever the reason, he’s gone. But he left no forwarding address, so the mail just keeps piling up inside the door.

A selection from Recessional by Jack Robinson, published by CB Editions. © Jack Robinson 2009.

Ten imperatives.

Posted: February 24, 2014 Filed under: Architectural, Crime and Punishment, Events, Graffiti, Lettering, Public Announcements, Shops | Tags: abney park cemetery, Banksy, miners' strike, Old Vic, Peter Sutcliffe trial Comments Off on Ten imperatives. Borough. © David Secombe 2010.

Borough. © David Secombe 2010.

Camden Lock. © David Secombe 1985.

Camden Lock. © David Secombe 1985.

Protestor outside the Old Bailey on the final day of the Peter Sutcliffe trial. © David Secombe 1981.

Protestor outside the Old Bailey on the final day of the Peter Sutcliffe trial. © David Secombe 1981.

Banksy stencil, Borough Market. © David Secombe 2003.

Banksy stencil, Borough Market. © David Secombe 2003.

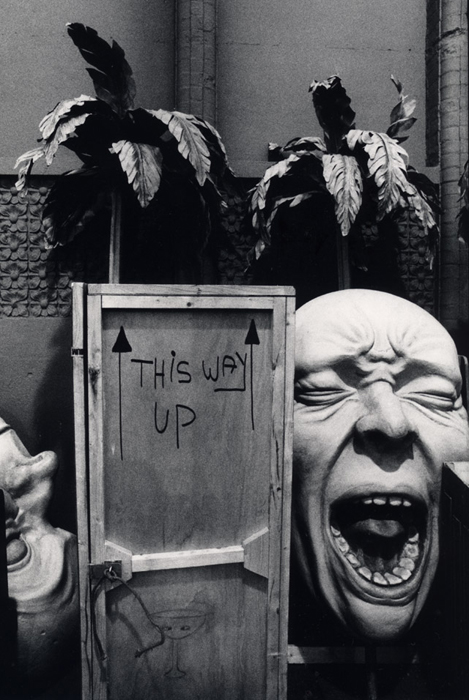

Props outside the stage door, Old Vic. © David Secombe 1988.

Props outside the stage door, Old Vic. © David Secombe 1988.

Pet shop, Brockley. © David Secombe 2003.

Pet shop, Brockley. © David Secombe 2003.

Abandoned pub, Bermondsey. © David Secombe, 2010.

Abandoned pub, Bermondsey. © David Secombe, 2010.

Pub toilet, Waterloo. © David Secombe 2008.

Pub toilet, Waterloo. © David Secombe 2008.

Sign outside a cafe, Brockley. © David Secombe 2010.

Sign outside a cafe, Brockley. © David Secombe 2010.

Abney Park Cemetery, N16. © David Secombe 2010.

Abney Park Cemetery, N16. © David Secombe 2010.

The Death of Dalston Lane.

Posted: February 13, 2014 Filed under: Architectural, Catastrophes, Conspiracies, Dereliction, Housing, Vanishings | Tags: Bill Parry-Davies, Dalston Lane, Death of London, hackney council, Iain Hamilton, Open Dalston Comments Off on The Death of Dalston Lane. Dalston Lane, May 2010. © David Secombe.

Dalston Lane, May 2010. © David Secombe.

From Open Dalston, 20 December & 11 February 2014:

Hackney to demolish sixteen Georgian houses in Dalston Lane

Dalston Lane, May 2010. © David Secombe.

Dalston Lane, May 2010. © David Secombe.

From Hackney, That Rose-Red Empire* by Iain Sinclair:

Dalston Lane

Once a street is noticed it’s doomed. Endgame squatters, slogans. DALSTON! WHO ASKED U? PROTECTED BY OCCUPATION. Torched terraces. Overlapping, many-coloured tags. Aerosol signatures on silver roll-down shutters. Scrofulous rubble held up by flyers for weekend noise events. THIS WORLD IS RULED BY THOSE WHO LIE. They said, the ones who make it their business to investigate such things, that there was a direct relationship between properties that applied for conservation status and arson attacks, petrol bombs. Unexplained fires. Moscow methods arrived in town with the first sniff of post-Soviet money. Russian clubs were opening in the unlikeliest places. We no longer had much to offer in the way of oil and utilities, energy resources, but we had heritage to asset-strip: Georgian wrecks proud of their status.

* Hamish Hamilton, 2009.

Dalston Lane, May 2010. © David Secombe.

Dalston Lane, May 2010. © David Secombe.

D.S.: The shameful saga of Dalston Lane is a microcosm of the fate of the East End as a whole: a sorry mash-up of corporate and council greed flying under the discredited banner of ‘regeneration’. The cynical, Blairite language of contemporary urban development expressed by developers and local authorities deserves a study in itself: ‘affordable housing’ (i.e. ‘unaffordable affordable housing’); councils ‘competing’ with other boroughs for resources (food? water? air?); ‘conservation-led schemes’ (wherein conservation is a synonym for demolition – along the lines of, ‘We had to demolish the terrace in order to conserve it.’). It is language that might have been invented by Orwell. The fact that a Labour council is responsible for such wanton cynicism towards its own residents is deeply depressing and makes one despair for the fate of the city. The death of Dalston Lane is the death of London.

For further reading on this long-festering matter, see Bill Parry-Davies’ site Open Dalston.

Sugary Fun.

Posted: January 30, 2014 Filed under: Architectural, Artistic London, Meteorological, Monumental, The Thames | Tags: Anish Kapoor, Britart, Carsten Holler, Dorothy Salcedo, Hyundai sponsorship, Robert Hughes, Tate Modern, Weather Project Comments Off on Sugary Fun. Tate Modern. © David Secombe 2004.

Tate Modern. © David Secombe 2004.

Robert Hughes, The New Shock of the New:

People need beauty. … And so, we seek out zones of silence and contemplation, arenas for free thought and regimented feeling. Museums have supplanted the church as places, both of social congress and of civic pride. They are the new cathedrals. And despite the dubious quality of some of the stuff that actually goes in them, or even outside them, there’s a growing hunger for the direct experience of art on a museum wall.

David Secombe:

Robert Hughes’s eloquent classification of galleries as cathedrals (from his 2004 documentary) is especially apt for Tate Modern. This post-industrial monument, the most popular modern art gallery anywhere, is situated plumb south of St Paul’s: twin bastions of belief squaring off across the Thames. You don’t have to be a religious person to love St Paul’s; but I don’t know how Christians who have lost their faith feel about it, or any other cathedral. Does it become a poignant symbol of loss, a reminder of disappointment?

Tate terrace, looking north. © David Secombe 2010.

Tate terrace, looking north. © David Secombe 2010.

Tate Modern has just announced that Hyundai has taken over (from Unilever) the sponsorship for its major space for new work, the Turbine Hall. The inaugural work for the Hall, Louise Bourgeois’s majestic Maman, was bound to be a tough act to follow, but since those spiders we’ve been treated to Anish Kapoor’s gargantuan ear trumpet, Dorothy Salcedo’s vandalism of the floor (which injured at least one unsuspecting elderly lady) and Carsten Holler’s slides, the hit of half-term: ingratiating, family-friendly, corporate-friendly installations that make good copy for broadsheet and tabloid alike. It has been hard to escape a growing sense that the Hall has become a sort of Battersea Funfair for the Boden set, a place where entertainment masquerades as cultural engagement.

Bankside. © David Secombe 2010.

Bankside. © David Secombe 2010.

Away from the vast Hall, the nannyish curation of the regular galleries seems intended to prevent the art from speaking for itself: one feels manipulated by an entity determined to impose itself between the art and the viewer. An unsympathetic observer might see Tate Modern as a temple underwritten by the bling of ‘BritArt’, an edifice dedicated to the Traceys and Damiens beloved of feature writers and plutocrats alike. Outside its walls one sees the monolithic, zone-changing retail development that follows artistic success like a blight: the contemporary equivalent of trinket-shit peddlers blistering the walls of medieval cathedrals. Bankside is Southbank east. (Psychogeographers will doubtless point to the golden age of Bankside, when The Globe, The Rose and The Swan premiered Shakespeare and his contemporaries, whilst punters not interested in the fate of Desdemona or the Duchess of Malfi could watch the bear-baiting. Modern Bankside doesn’t offer any bear pits, but there’s a Pizza Express and at least one Starbucks.)

But the building remains sublime, even if its function as a gallery is compromised by the fact that (like the Guggenheim galleries in New York and Bilbao) its architecture overpowers the greater proportion of its content. And it would be bilious to deny that the Turbine Hall occasionally hosts something really good. As Robert Hughes concluded in The New Shock of the New: ‘We’re seeking value, looking for meaning, a place outside ourselves that tells us there more to life than our everyday concerns and needs. You could see this in the crowds gathering for Olafur Eliasson’s Weather Project in the Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern. Hundreds of monofilament lamps that suppressed all colours except yellow, shedding a gold light through gloomy air thickened by fog machines underneath a mirrored ceiling. People lay on the floor, staring up at themselves reflected in that ceiling, lit by the pale yellow light of their new sun god’.

Weather Project installation, Tate Modern. © David Secombe 2004.

Weather Project installation, Tate Modern. © David Secombe 2004.

‘The success of the Weather Project with its two million visitors shows that the hunger for new art is as strong as ever. The idea that aesthetic experience provides a transcendent understanding is at the very heart of art. It fulfils a deep human need. And despite the decadence, the confusion and the brouhaha, the desire to experience it, live with it and learn from it remains immortal’.