Old and New Soho. Photo & text by Mark Granier (4/5)

Posted: May 26, 2011 Filed under: Amusements, Bohemian London, Interiors, Lettering, London Labour Comments Off on Old and New Soho. Photo & text by Mark Granier (4/5)Soho, 2010. Photo © Mark Granier.

Mark Granier writes:

My cousin was working in London for a few months, so when I came over from Dublin we met up a couple of times. One evening we went to the ‘Exposed’ exhibition of photography at Tate Modern, concerned with ‘Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera.’ They had stretched the theme a little, so that it practically became a history of the art, taking in all kinds of street/reportage/war photography, from the 1930s (or possibly earlier) – Brassaï, Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, etc. – right up to contemporaries such as Nan Goldin. Afterwards, we found a little restaurant in her favourite part of the city, Soho. My cousin is a smoker, so we sat at a table on the sidewalk, talking and watching the variegated street-life. When the place closed we ambled through the surrounding streets.

I love the blurring of boundaries in Soho – music, art, food, sex – the city in microcosm. Just before hailing a taxi, we noticed this doorway, with its eloquent one-word sign, and it was like encountering an annex to the exhibition, an intimate little theatre/Tardis that opened a corridor between centuries. The photograph took itself before I clicked the shutter. The poem, such as it is, took a little longer:

OPEN

said the handmade sign

(underscored by a red arrow)

inside a doorway one step

from a Soho street. We stopped

just a tick, then longer, as if

we had some business here

other than letting our eyes

travel the strip-lit grey

narrowing walls, torn lino,

lines draining like a sink

to a high arch, behind which

steel-edged stairs further the lesson

in perspectives: the whoosh of

compressed centuries, a lost

hunting cry, razzmatazz, brass

rubbings of jazz, appetite’s

arrows, harnesses, taxies

and here’s one now –

… for The London Column. © Mark Granier 2011

Old and New Soho. Photo John Claridge, text Sebastian Horsley (3/5)

Posted: May 25, 2011 Filed under: Artistic London, Bohemian London | Tags: John Claridge, Sebastian Horsley, The French House Comments Off on Old and New Soho. Photo John Claridge, text Sebastian Horsley (3/5)Sebastian Horsely, The French House, Soho, 2002. Photo © John Claridge.

Clearly God loves ugly people. He makes so many of them. He shows his contempt for life by the kind of person he selects to receive it. Crawling from primeval waters you waddled, slaves, cripples, imbeciles, the simple and the mighty, fighting for the right to breathe oxygen. It was a mistake but you did it. Little did it matter to you that the earth was a vale of tears, of horrid sufferings, of torturous sickness and death. You wanted life little worm. You got it.

And what did you do with it when you got it? Celebrate? Have fun? No. You moaned. Equal rights! Equal pay! Equal Equal! Equal is a dead word. No man who says “I am as good as you” believes it. The shark never says it to the sardine, nor the intelligent to the stupid, nor the rich to the poor, nor the beautiful to the plain. The claim to equality is made only by those who feel themselves to be in some way inferior.

And inferior they are. With beautiful classical things like me the Lord finished the job. Ordinary ugly people know they’re deficient and they go on looking for the pieces, moaning and complaining. Don’t you realise my darlings that if you have any complaints, they would be theistic : – they should be about your maker , who lets face it, hasn’t done that great a job.

Physical beauty is the sign of an interior beauty, a spiritual and moral beauty. The handsome are not merely blessed with their looks, they are somehow better than the plain and ugly : they are wittier, more intelligent, even tempered and socially competent. Ms Sappho put it more bluntly : “What is beautiful is good”

What I hate most about ugliness is that it shows such bad judgement. Much as I loathe ugly people our sympathies should not, however, be for them after all. I mean their faces they are behind – they can’t see their revolting selves. We, the public, on the other hand, are in front of them and can see all too clearly. And its simply not good enough. No its not. How dare they look like that? Don’t they realise that their right to look revolting ends where it meets my eye?

[From Sebastian Horsley‘s blog, October 05, 2008. Horsely died of a drug overdose at his house in Meard Street, Soho, in June 2010.]

Old and New Soho. Photo & text John Londei. (2/5)

Posted: May 24, 2011 Filed under: Bohemian London, Pubs | Tags: Gaston Berlemont, John Londei, The French House Comments Off on Old and New Soho. Photo & text John Londei. (2/5)Gaston’s farewell party, French House, Soho. Photo © John Londei 1989.

John Londei writes:

The French House, Dean Street, W1

Gaston Berlemont, and his handlebar moustache, was as much a feature of Soho as the pub he ran. Born in a room above the pub in 1914, Gaston was still at school when he first started serving behind the bar in the evenings. Seventy-five years later the moment had arrived for his final ‘Time Gentlemen, please’.

Gaston’s father, Victor – the first foreigner to be granted a full English pub licence in 1914 – took the pub over from a German who, at the outbreak of World War One, feared internment as an enemy alien. It was actually called the ‘York Minister’ but with the arrival of the Berlemonts’, locals nicknamed it ‘The French’, and it wasn’t until 1977 that its name officially changed to ‘The French House’. In earlier days Soho was somewhat of a Gallic enclave with its own French butcher, patisserie, newsagent, cafes, restaurants and two churches. During World War Two the Free French made ‘The French’ their drinking HQ, and it’s thought General De Gaulle wrote his 1940 clarion call speech À tous les Français in an upstairs room at the pub declaring that one day France would be liberated from Nazi occupation.

Victor Berlemont died in 1951 and Gaston took over the pub. Under his tenure the pub remained unchanged; the décor remained a sombre brown, and wines, apéritifs, and spirits were the tipples of choice. It must be the only British pub where beer was served in half-pint glasses. And as for buying a packet of crisps, peanuts or pork scratchings, forget it, Gaston refused to stock them. But the unique character of the pub and its eccentric landlord had many luminaries as regulars such as Augustus John, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, Dylan Thomas, Brendan Behan, Max Beerbohm, Jeffrey Bernard and Peter O’Toole. Even Edith Piaf and Maurice Chevalier visited the pub.

On Friday 14 July 1989, Gaston retired. And of course, being Gaston, he didn’t choose just any old day to go en retraite – he choose Bastille Day, and moreover it was the day marking the storming of the Bastille’s bicentennial. And of course, Soho being Soho wasn’t about to mark the retirement of its longest established patron without throwing a lavish party that resulted in Dean Street being closed to traffic, and the pub having to close twice in order to replenish the stock of booze.

It was a magical day, albeit a day tinged with sadness at having to bide adieu to one of Soho’s favourite sons. Gaston had planned to give a speech from the first-floor window, but the inebriated roars of appreciation from the crowd were such that he couldn’t be heard, so he waved instead. Afterwards he told a reporter that he had intended to say. “Vive La France, Vive L’Angleterre, Vive La Paix.”

An obituary appearing in the Independent newspaper in 1999 reported: Gaston Roger Berlemont, publican: born London 26 April 1914; three times married (one son, two daughters); died London 31 October 1999.

… for The London Column. © John Londei 2011.

Old and New Soho. Photo & text Angus Forbes (1/5)

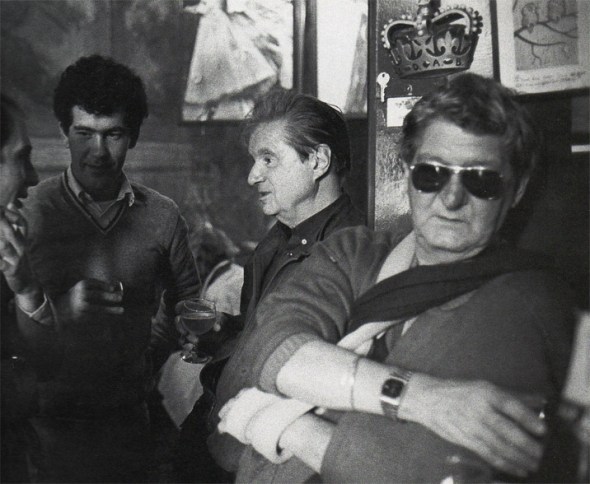

Posted: May 23, 2011 Filed under: Artistic London, Bohemian London | Tags: Angus Forbes, Colony Room, Francis Bacon, Ian Board, Old Soho, Patrick Caulfield Comments Off on Old and New Soho. Photo & text Angus Forbes (1/5)Francis Bacon (centre) and Ian Board (right) in the Colony Room, 1983. Photo © Angus Forbes.

Angus Forbes writes:

September 1983: the book publisher Malcolm McGregor is organising A Day in the Life of London, and the commissioning photographer Red Saunders wants me in. I tell Red I’ll cover legal London in the morning and the West End drinking clubs, of which at that time I was a frequentee, in the afternoon. On the day (Friday, September 14) I roll up at the Colony Room in Dean Street shortly after opening, at half three. The sun is reflecting off the buildings opposite and streaming through the first-floor window. I’m a member there, so I tell the irascible owner Ian Board what I’m doing and would it be OK if I took some casual, non-flash pictures? Ian’s in a mellowish state today and says yes. It’s early for the Colony and people are only just starting to drift in. I take some pictures, nothing special, and am thinking of moving on when Ian says don’t go, Francis will be here in a minute. Francis Bacon. By the time Bacon and team arrive, the drinkers have become accustomed to my Nikon-wielding antics and I ask Francis if I can take some of him too. He does not demur. My scoop in the bag, I head off to The Little House, a similar establishment in Shepherd Market, and sitting at the bar is Patrick Caulfield.

A few days later and I’m viewing the contact sheets in my darkroom in Chancery Lane. It occurs to me that by simple photocomposition I could combine the images of Francis and Patrick and drop Bacon into The Little House (which I know he uses, as that’s where I first met him). A double-scoop. But to carry it through to print, fresh permissions must be sought. I arrive at the Colony at about seven. Ian’s paralytic and his barman, Michael Wojas, is pretty well-advanced himself. I have with me three photographic enlargements: one is the shot of Ian and Francis in the Colony, another shows Patrick at The Little House and the third is a mock-up of the proposed photocomp. I show Ian the first shot and he likes it; Francis’ champagne glass is at the right angle, and Ian, arm in a sling from some rough, looks suitably mad. Next shot: indifference. But when Ian Board sees the mock-up of his Francis in a rival hostelry, all hell breaks loose.

So incensed is Ian by the image I’ve just shown him, he pitches forward and topples onto the foetid, cigarette-scorched carpet of the notorious green boite with an almighty, clattering thump. When Michael and I manage to heave him back onto his throne, Ian’s right index finger is dripping blood. He grabs the mock-up and starts jabbing at it, daubing it with dollops of his own blood. ‘It’s a disgrace! It’s an insult!’ shrieks Ian, lunging for the telephone. He gets Bacon on the line. ‘Know what that cunt photographer wanker’s done?’ Ian bellows, ‘He’s only put you in that fat Jamaican whore’s place with someone called ‘Cauliflower’ or something!’ He thrusts the phone to me. ‘Francis wants to speak to you!’ ‘The negatives must be destroyed!’ Bacon booms. He’s drunk as well and now I’m downing vodkas like there’s no Sunday – this photocomp’s not such a good idea after all. ‘Francis, I wouldn’t dream of publishing without your say-so. I just thought that as you and Patrick use the same places…’ ‘Who?’ he interrupts. ‘Patrick Caulfield’ I say. ‘Never heard of him!’ Bacon thunders.

Later I relate the story to Gerry Clancy. He tells me that not long ago Bacon had turned up at an opening at Fischer Fine Art where Caulfield was showing miniatures. Francis had proceeded to walk round the gallery, dashing the works from the wall, muttering ‘Postage stamps! Postage stamps!’ After the affair has subsided I see Patrick in the Zanzibar with John Hoyland. I repeat the Colony tale, including Bacon’s last remark to me. Patrick Caulfield bursts into tears.

Red Saunders uses my shot of Bacon and Board as a double-page spread in A Day in the Life of London. A decade later and all has long been supposedly forgiven. Francis has been dead for three years and a framed print of my shot of him and Ian has been hanging in the Colony since the time it was taken. Ian Board is on his usual perch and I’m at the next barstool knocking back the tonic water. We’re having a desultory conversation about nothing in particular, no animosity, when Ian suddenly reaches behind him, seizes the framed print from the wall and smashes it over my head. A rivulet of blood runs down my nose and splashes onto the palm of my hand. I turn to Ian in astonishment.

‘Cunt!’ says Ian Board.

© Angus Forbes 2011