Swansong.

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones 6 Comments Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

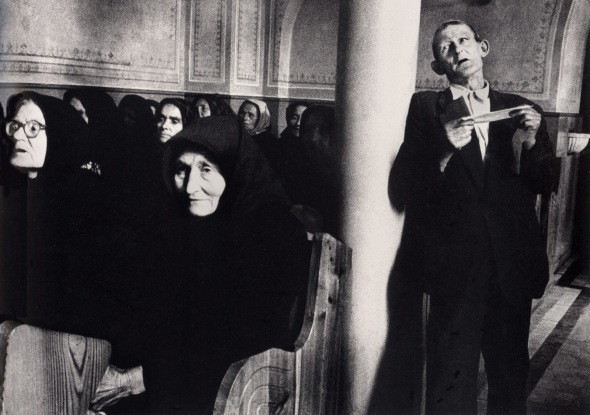

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

Old and New Soho. Photo & text Angus Forbes (1/5)

Posted: May 23, 2011 Filed under: Artistic London, Bohemian London | Tags: Angus Forbes, Colony Room, Francis Bacon, Ian Board, Old Soho, Patrick Caulfield Comments Off on Old and New Soho. Photo & text Angus Forbes (1/5)Francis Bacon (centre) and Ian Board (right) in the Colony Room, 1983. Photo © Angus Forbes.

Angus Forbes writes:

September 1983: the book publisher Malcolm McGregor is organising A Day in the Life of London, and the commissioning photographer Red Saunders wants me in. I tell Red I’ll cover legal London in the morning and the West End drinking clubs, of which at that time I was a frequentee, in the afternoon. On the day (Friday, September 14) I roll up at the Colony Room in Dean Street shortly after opening, at half three. The sun is reflecting off the buildings opposite and streaming through the first-floor window. I’m a member there, so I tell the irascible owner Ian Board what I’m doing and would it be OK if I took some casual, non-flash pictures? Ian’s in a mellowish state today and says yes. It’s early for the Colony and people are only just starting to drift in. I take some pictures, nothing special, and am thinking of moving on when Ian says don’t go, Francis will be here in a minute. Francis Bacon. By the time Bacon and team arrive, the drinkers have become accustomed to my Nikon-wielding antics and I ask Francis if I can take some of him too. He does not demur. My scoop in the bag, I head off to The Little House, a similar establishment in Shepherd Market, and sitting at the bar is Patrick Caulfield.

A few days later and I’m viewing the contact sheets in my darkroom in Chancery Lane. It occurs to me that by simple photocomposition I could combine the images of Francis and Patrick and drop Bacon into The Little House (which I know he uses, as that’s where I first met him). A double-scoop. But to carry it through to print, fresh permissions must be sought. I arrive at the Colony at about seven. Ian’s paralytic and his barman, Michael Wojas, is pretty well-advanced himself. I have with me three photographic enlargements: one is the shot of Ian and Francis in the Colony, another shows Patrick at The Little House and the third is a mock-up of the proposed photocomp. I show Ian the first shot and he likes it; Francis’ champagne glass is at the right angle, and Ian, arm in a sling from some rough, looks suitably mad. Next shot: indifference. But when Ian Board sees the mock-up of his Francis in a rival hostelry, all hell breaks loose.

So incensed is Ian by the image I’ve just shown him, he pitches forward and topples onto the foetid, cigarette-scorched carpet of the notorious green boite with an almighty, clattering thump. When Michael and I manage to heave him back onto his throne, Ian’s right index finger is dripping blood. He grabs the mock-up and starts jabbing at it, daubing it with dollops of his own blood. ‘It’s a disgrace! It’s an insult!’ shrieks Ian, lunging for the telephone. He gets Bacon on the line. ‘Know what that cunt photographer wanker’s done?’ Ian bellows, ‘He’s only put you in that fat Jamaican whore’s place with someone called ‘Cauliflower’ or something!’ He thrusts the phone to me. ‘Francis wants to speak to you!’ ‘The negatives must be destroyed!’ Bacon booms. He’s drunk as well and now I’m downing vodkas like there’s no Sunday – this photocomp’s not such a good idea after all. ‘Francis, I wouldn’t dream of publishing without your say-so. I just thought that as you and Patrick use the same places…’ ‘Who?’ he interrupts. ‘Patrick Caulfield’ I say. ‘Never heard of him!’ Bacon thunders.

Later I relate the story to Gerry Clancy. He tells me that not long ago Bacon had turned up at an opening at Fischer Fine Art where Caulfield was showing miniatures. Francis had proceeded to walk round the gallery, dashing the works from the wall, muttering ‘Postage stamps! Postage stamps!’ After the affair has subsided I see Patrick in the Zanzibar with John Hoyland. I repeat the Colony tale, including Bacon’s last remark to me. Patrick Caulfield bursts into tears.

Red Saunders uses my shot of Bacon and Board as a double-page spread in A Day in the Life of London. A decade later and all has long been supposedly forgiven. Francis has been dead for three years and a framed print of my shot of him and Ian has been hanging in the Colony since the time it was taken. Ian Board is on his usual perch and I’m at the next barstool knocking back the tonic water. We’re having a desultory conversation about nothing in particular, no animosity, when Ian suddenly reaches behind him, seizes the framed print from the wall and smashes it over my head. A rivulet of blood runs down my nose and splashes onto the palm of my hand. I turn to Ian in astonishment.

‘Cunt!’ says Ian Board.

© Angus Forbes 2011