Drinker’s London. Photo Paul Barkshire, text David Secombe. (1/5)

Posted: October 18, 2011 Filed under: Clubs, Eating places | Tags: Chez Gerard, covent garden, Garrick Club, L'Estaminet, Le Beaujolais, Le Tartin, merguez sausages Comments Off on Drinker’s London. Photo Paul Barkshire, text David Secombe. (1/5) Floral Street, Rose Street & Garrick Street, 1986. Photo © Paul Barkshire.

Floral Street, Rose Street & Garrick Street, 1986. Photo © Paul Barkshire.

This week’s offering on The London Column consists of Paul Barkshire’s limpid photographs of drinking establishments from the 1980s, accompanied by personal observations on city drinking by myself and – if we’re lucky – a few others.

It seems appropriate to begin the week with this picture, which shows the convergence of three Covent Garden streets, the noble facade of the Garrick Club facing towards us, and – the reason for its appearance here – chefs from the kitchen of an establishment fondly remembered by your correspondent. They are standing in the doorway of what used to be the restaurant L’Estaminet, and its downstairs wine bar Le Tartin.

L’Estaminet was established by the remnants of the team who had started the original Chez Gerard, the steak-frites operation on Charlotte Street. I would eat upstairs occasionally, but it was usually easier to stay in the basement bar. Behind the counter downstairs were Bernard and Gerard: the former bespectacled, austere, and slightly forbidding, Gerard an endearingly hectic shambles. A gamine waitress was on hand to smile at the patrons’ terrible jokes and give the middle-aged regulars dreams of a better life. Le Tartin was an oasis of calm amidst the frantic tourist clamour outside, offering a far more intimate experience than any other London bar or club I can think of. Sat at a booth one could drink and dream one’s life away in the gloom, and they would bring you merguez sausages if your reverie made you hungry.

I was a regular there for about seven years, until that sad evening when my regular visit revealed the dead hand of new management (who went on to rename the venue The Forge). Bewildered, my colleague and I retreated to the nearby Le Beaujolais (another venerable French-run wine bar, although a much more raucous affair) where we were told the sorry tale of the departure of Bernard, Gerard et al. The staff of Le Beaujolais were sympathetic to our distress, because they understood what we had become: exiles. D.S.

… for The London Column.

See also: London Perceived no.1

London Perceived. Text V.S. Pritchett, photos Evelyn Hofer (1/5)

Posted: July 25, 2011 Filed under: Clubs, Eating places, Literary London, London Types | Tags: Evelyn Hofer, Garrick Club, London Perceived, V.S. Pritchett 1 CommentHead waiter, Garrick Club, 1962. Photo © Estate of Evelyn Hofer

V.S. Pritchett writing in London Perceived*, 1962:

And what happens in square and pubs goes on in clubs, all the thousands of drinking clubs, the luncheon clubs, the dining clubs, the sporting clubs, the dance clubs, to the great clubs around Pall Mall and St. James’s. You are a Londoner, ergo you are a member. You are proposed and seconded; that done, you are among a few friends; you have your home from home. In none of these clubs is any utility of purpose frankly admitted. It is true that Bishops and Fellows of the Royal Society gather at the Atheneaeum; actors, publishers, and the law at the Garrick; the aristocracy and the top politicians at Boodle’s, White’s, or Brooks’s; that, following Stevenson and Kipling, a lot of bookish, professorial and civil wits are at the Savile, and professional eminences at the Reform, where Henry James had a bedroom with a spy hole cut in the door so that the servant could see whether the master was sleeping and refrain from disturbing him. (The hole is still there.)

Clubs change. London is made for males and its clubs for males who prefer armchairs to women. The great clubs are in difficulties. Their heyday was the Victorian age, when men did not go home early in the evenings; now at night they are empty of all but a few bachelors, sitting in the drying leather chairs. Some clubs have tried allowing ladies to dine in the evening, but the ladies, after the first riush of curiosity, in which they hoped to find out what happy vices their men were comfortably practising there, tend to be appalled by these mausoleums of inactive masculinity, even when they are elegant, and tend to be depressed by the gravy-coloured portraits on the walls. The architecture, gratifying to male self-esteem, does nothing for the sex, and the boredom that hangs like old cigar smoke in the air is a sad reminder of the most puzzling thing in the sex war: that men lie each other, rather as dogs like each other. The food is dull, but a point that the ladies overlook is that the wine is excellent and cheap.

How did this taste for clubs begin? Did it start with the witenagemot or the monasteries? Did it sprout from the guilds – for what are the Drapers’, the Fishmongers’, the Armourers’, the Watermens’, the Grocers’ companies, with their medieveal robes and seremonies, but medieval guilds turned into clubs for the Annual Dinner? The clubs start, as the whole of visible London does, except the Tower and Westminster Abbey, St. Bartholomew and the Elizabethan buildings in Staple Inn – the clubs start with the greatest of all london inventions: modern mercantile capitalism. They began with the coffee houses in the City. “We now use the word ‘club'”, Pepys wrote, “for a sodality in a tavern”. Lloyds was a coffee house, the place where one could read a paper and hear the news, and the more one sat about there, the more one heard. They were often started by servants – the most domineering of men – by the race of Jeeves, for the Woosters, the masters of the world; fashionable clubs like Boodle’s, Brooks’s, White’s take their names form the servants who founded them. The idea has the ease of Nature, and it is only in the nineteenth century, when industrial wealth came in, that clubs like the Public Schools, became outwardly pretentious and expensive.

* © 1962 and renewed 1990 by V.S. Pritchett. Used by permission of David R. Godine, Publisher, Inc.

[Special thanks in assembling this week’s feature are due to: Jim McKinniss; Mark Giorgione of the Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California; Andreas Pauly at the Hofer Estate; and Carl Scarbrough at David Godine. D.S.]

Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Robert Elwall. (3/3)

Posted: May 19, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Eating places, Interiors, London Types | Tags: Architectural Review, Manplan, Pepys Estate, RIBA, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Robert Elwall. (3/3)Canteen for the elderly, Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo Tony Ray-Jones © RIBA Photographs Library.

Robert Elwall writes:

In 1969 Hubert de Cronin Hastings, owner of the Architectural Press and editor of its leading journal, the Architectural Review, decided to experiment with a new look for the magazine. He accordingly launched the ‘Manplan’ series published in eight themed issues between September 1969 and September 1970. Rather than being illustrated by the Review’s usual staff photographers, Hastings commissioned photographs from some of the leading photojournalists of the day asking them to cast their lenses in judgement on the contemporary state of architecture and town planning. Thus Ian Berry illustrated two issues on communications and health and welfare while his Magnum colleague, Peter Baistow, also supplied the images for two, those on religion and local government. Other contributors were Tom Smith on education; Tim Street-Porter on industry and Tony Ray-Jones on housing. The series kicked off with a typically hard-hitting issue on ‘Frustration’ with photographs by Patrick Ward.

These images were totally unlike anything that had been seen in the Review before. Ironically the Review had done much to formulate the norms of mainstream architectural photography with dramatically hagiographic renditions of pristinely new buildings set beneath sunlit skies and photographed with large format cameras. Instead it now offered its readers harsh, grainy, 35mm images of a grimly dystopian world the photographers argued that architects and planners had created. The unrelenting grimness and claustrophobic intensity of the photographs was magnified by the use of wide-angle lenses which had the effect of thrusting the viewer into the frame; by the reproduction of the photographs in a specially devised matt-black ink; and by the provision of hard-hitting captions that sometimes were printed over the images. Not surprisingly the series proved too much for many of the Review’s architect subscribers and in the face of falling circulation figures Hastings was forced to admit defeat and abandon his experiment.

Despite being short-lived, ‘Manplan’ can be regarded as the high watermark of photojournalism applied to architectural photography. During the 1960’s this had been pioneered by magazines such as Architectural Design, which in September 1961 had published a special issue on Sheffield illustrated by the great photojournalist Roger Mayne and by photographers such as John Donat (1933-2004) who, much influenced by Mayne’s example, took advantage of the smaller format cameras and faster films then appearing on the market to show how buildings interacted with, and were experienced by, their users and the public. For so long banished from the architectural photographer’s frame, real people going about real tasks, rather than merely included to give a sense of scale, now became the norm. By the 1970s, however, this application of the tenets of photojournalism and street photography to architecture was drawing to a close. There were two main reasons for this. Firstly, owing to the slow speed of large format colour films and the elaborate lighting set-ups they often required, the explosion in colour photography placed a renewed emphasis on architecture’s more formal qualities at the expense of human activity. In addition the increased commissioning of photography by architects themselves rather the more independently-minded magazines inevitably premiated eye-catching imagery that would show architects’ works in the best light. However, it is pleasing to reflect that today ‘Manplan’ has found favour once again as photographers once more seek to deviate from the norms.

… for The London Column. © Robert Elwall 2011

[Robert Elwall is Assistant Director, Photographs, Imaging & Digital Development of the British Architectural Library at the Royal Institute of British Architects.]

Welcoming smiles … (1/3)

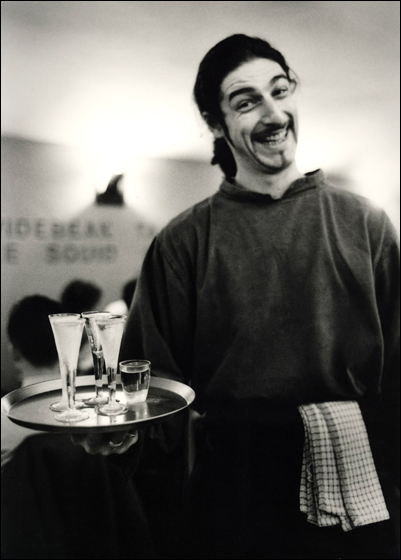

Posted: May 4, 2011 Filed under: Eating places, London Types, Public Announcements Comments Off on Welcoming smiles … (1/3)Belgo, Camden. © David Secombe 1992

From Gumtree, 27th February 2010:

French waiter is looking for a summer job …

hi my name is jean, i’ll be graduated in france at the end for may. i need for my job to practis my english. i’m totally able to speak with english guest and anderstand what they need. …

David Secombe writes:

Welcome to the London Column. This site is dedicated to photography and writing from London.

The site is edited by myself and will feature contributions from some of the best writers and photographers from the past sixty years.

Now read on …