Swansong.

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones 6 Comments Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

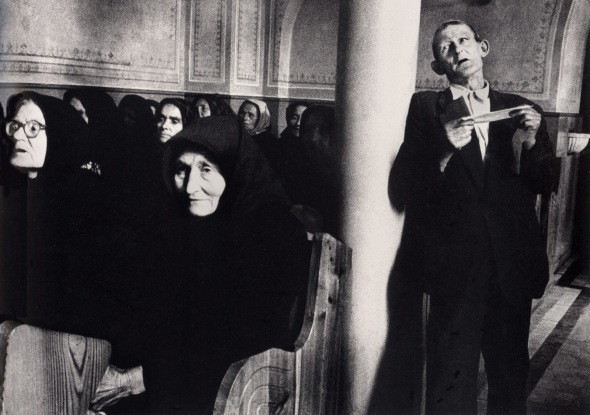

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Robert Elwall. (3/3)

Posted: May 19, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Eating places, Interiors, London Types | Tags: Architectural Review, Manplan, Pepys Estate, RIBA, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Robert Elwall. (3/3)Canteen for the elderly, Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo Tony Ray-Jones © RIBA Photographs Library.

Robert Elwall writes:

In 1969 Hubert de Cronin Hastings, owner of the Architectural Press and editor of its leading journal, the Architectural Review, decided to experiment with a new look for the magazine. He accordingly launched the ‘Manplan’ series published in eight themed issues between September 1969 and September 1970. Rather than being illustrated by the Review’s usual staff photographers, Hastings commissioned photographs from some of the leading photojournalists of the day asking them to cast their lenses in judgement on the contemporary state of architecture and town planning. Thus Ian Berry illustrated two issues on communications and health and welfare while his Magnum colleague, Peter Baistow, also supplied the images for two, those on religion and local government. Other contributors were Tom Smith on education; Tim Street-Porter on industry and Tony Ray-Jones on housing. The series kicked off with a typically hard-hitting issue on ‘Frustration’ with photographs by Patrick Ward.

These images were totally unlike anything that had been seen in the Review before. Ironically the Review had done much to formulate the norms of mainstream architectural photography with dramatically hagiographic renditions of pristinely new buildings set beneath sunlit skies and photographed with large format cameras. Instead it now offered its readers harsh, grainy, 35mm images of a grimly dystopian world the photographers argued that architects and planners had created. The unrelenting grimness and claustrophobic intensity of the photographs was magnified by the use of wide-angle lenses which had the effect of thrusting the viewer into the frame; by the reproduction of the photographs in a specially devised matt-black ink; and by the provision of hard-hitting captions that sometimes were printed over the images. Not surprisingly the series proved too much for many of the Review’s architect subscribers and in the face of falling circulation figures Hastings was forced to admit defeat and abandon his experiment.

Despite being short-lived, ‘Manplan’ can be regarded as the high watermark of photojournalism applied to architectural photography. During the 1960’s this had been pioneered by magazines such as Architectural Design, which in September 1961 had published a special issue on Sheffield illustrated by the great photojournalist Roger Mayne and by photographers such as John Donat (1933-2004) who, much influenced by Mayne’s example, took advantage of the smaller format cameras and faster films then appearing on the market to show how buildings interacted with, and were experienced by, their users and the public. For so long banished from the architectural photographer’s frame, real people going about real tasks, rather than merely included to give a sense of scale, now became the norm. By the 1970s, however, this application of the tenets of photojournalism and street photography to architecture was drawing to a close. There were two main reasons for this. Firstly, owing to the slow speed of large format colour films and the elaborate lighting set-ups they often required, the explosion in colour photography placed a renewed emphasis on architecture’s more formal qualities at the expense of human activity. In addition the increased commissioning of photography by architects themselves rather the more independently-minded magazines inevitably premiated eye-catching imagery that would show architects’ works in the best light. However, it is pleasing to reflect that today ‘Manplan’ has found favour once again as photographers once more seek to deviate from the norms.

… for The London Column. © Robert Elwall 2011

[Robert Elwall is Assistant Director, Photographs, Imaging & Digital Development of the British Architectural Library at the Royal Institute of British Architects.]

Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Owen Hatherley (2/3)

Posted: May 18, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Interiors | Tags: Owen Hatherley, Pepys Estate, RIBA, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Owen Hatherley (2/3)Elderly resident, Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo Tony Ray-Jones © RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Owen Hatherley writes:

Like a lot of council estates that have been subjected to the ministrations of ‘regeneration’, there are certain myths about the Pepys Estate. Each has a grain of truth, each covers up what ought to be a larger, more overwhelming truth.

My own experience of the place is fairly limited. I recall walking there from a flat in the centre of Deptford to hand in my form for the council waiting list; on a few other occasions I would wander over to use the bridge that connected the estate to Deptford Park, just for the fun of it, for the fact of its mere existence. The place seemed quiet during the day; I only saw it at night as the N1 bus looped around it. So I can’t offer much insight into what it was ever like to live there, but I have watched the material transformations of the place over the last decade or so, and watched the media discourse around it spin its web.

The Pepys is often presented as a monolithic, monstrous estate that was a failure from day one. Which is interesting, as the place marked one of the earliest council schemes to preserve as well as demolish – the little enclaves of Georgian nauticalia that mark the estate’s edges were part of the scheme, renovated and let by the council as an integral element, by now surely long since lost to Right to Buy. The rest of it is, or rather was, a series of jagged, mid-rise blocks connected by walkways, enclosing three towers and a large open space, with the bridges eventually leading to a park on the other side of Evelyn Street. In the middle is a community building with a bizarre, expressionist roofline seemingly partly based on oast houses (but then, so is Bluewater).

What is undoubtedly true is that parts of it were badly made – the lifts were apparently prone to breakdown from extremely early on. The draughty blocks were clad in plasticky white material at some point in the 1980s. Yet what happened when the place got ‘regenerated’ is by far the most dramatic aspect. The open space went, with low-rise flats to be sold to ‘key workers’ and on the open market taking an already highly dense area and making it more so. This accordingly makes it more ‘mixed’, ‘vibrant’ and ‘urban’, as professionals now live alongside – well, not quite alongside, but at least near to, council tenants.

The bridge over Evelyn Street went also, with remarkably clumsy ‘eco-flats’ (you can tell this, because the extra layer of curved glass on the façades a few feet from the actual windows could surely have no other possible functional justification) built where it met the park. This ‘recreated a street pattern’ in the area according to planning ideologists; or it defaced an area of public space. As you wish.

The new blocks are regeneration hence good, the old are council housing hence bad. Yet the council flats are much larger, and look much more robustly built, of concrete and stock brick – the newer flats are clad in the ubiquitous thin layer of brick or attached slatted wood, materials which have shown an unfortunate tendency to fall off. The major story is with one of the three towers – the one nearest to the river, naturally – which was completely cleansed of undesirables and sold instead as Z Apartments, luxury riverside living. It became a brief cause celebre via class war reality TV show The Tower.

All this, in theory, funds the regeneration, meaning in this case the cleaning and patching up, of the older buildings, or alternatively to their phased, currently seemingly stalled, demolition. None of the new buildings in the Pepys Estate – or anywhere else in London – have been council housing, though its regeneration has entailed several once council flats going private. The waiting list, nationally, is reckoned to be five million.

… for The London Column. © Owen Hatherley 2011.

Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman. (1/3)

Posted: May 17, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Literary London, London on film, London Places | Tags: Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman, Pepys Estate, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman. (1/3)Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo © Tony Ray-Jones/RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Edward Mirzoeff writes:

Bird’s-Eye View was a pioneering series of 13 films shot entirely from a helicopter. For the first of these, The Englishman’s Home (BBC2 5 April 1969) John Betjeman wrote in the commentary about the new high-rise blocks. At the time his strongly-felt views were very much against progressive liberal thinking on the subject, and what he wrote was attacked and derided. By now most people have come round to his old-fashioned but humane way of thinking.

Betjeman refused to fly in the helicopter, but wrote his commentary, in verse, over weeks in the cutting room, once the picture-editing had been completed.

[Edward Mirzoeff was the producer of Bird’s Eye View.]

Pepys Estate, Deptford by John Betjeman:

Where can be the heart that sends a family to the 20th floor

In such a slab as this.

It can’t be right, however fine the view

Over to Greenwich, and the Isle of Dogs.

It can’t be right, caged halfway up the sky

Not knowing your neighbour, frightened of the lift,

And who’ll be in it, and who’s down below

And are the children safe?

What is housing if it’s not a home?”

[Tony Ray-Jones was one of Britain’s finest photographers, whose early death – at just 30 – in 1972 robbed us of an artist of acute insight and integrity. His book A Day Off is celebrated as one of the definitive post-war photographic studies of British life, and influenced a generation of native photographers, not least Martin Parr whose early work showed an obvious debt to Ray-Jones. Until I went searching for means of contacting the Ray-Jones estate, I was unaware of his work for Architectural Review in 1970: a total of 138 pictures that are now in the RIBA photographic library. These are images of the impact of modern housing, and he responded to the brief with characteristic power; he seems to have been especially engaged with the London subjects – Deptford, Thamesmead, the Old Kent Road, etc. – and some of these pictures are the equal of his better-known work. The London Column will be running a further two images from TRJ’s series on the Pepys Estate later this week. Special thanks to Robert Elwall at RIBA Library Photographs for allowing us to reproduce them here. D.S.]