Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (2/5)

Posted: December 6, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Wildlife | Tags: London Zoo, Regent's Park, Sir Stamford Raffles Comments Off on Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud. (2/5)Black-Footed (Jackass) Penguin, Zoo Series, London 1995. © Britta Jaschinski.

Randy Malamud writes:

Walking in the Zoo, walking in the Zoo.

The O.K. thing on Sunday is the walking in the Zoo.

So sang Victorian music-hall artist Alfred Vance – the Great Vance! – in 1870, appearing as a dandy London “swell” recounting his excursion to Regent’s Park. The Fellows of the Zoological Society of London were not amused by his contribution of the word “zoo” to the lexicon, dismayed that the common monosyllabic moniker trivialized their importance.

“ZSL London Zoo,” as it calls itself today, opened to the Fellows of the Society in 1828, and to paying visitors from the public at large in 1847. Some of its cages (or “enclosures,” in today’s softer euphemism of zoo discourse) date back to that era: the Raven’s Cage was erected in 1829, and the Giraffe House still in use was built in the 1830s.

Walking in the zoo today, one feels many shadows of the past: not just from the physical compound of Decimus Burton’s nineteenth-century architecture and grounds, but also from the historical legacy of imperialism. The zoo was the project of Sir Stamford Raffles, imperialist extraordinaire. His day job was subduing and plundering Java and Sumatra as a colonial agent for the East India Company. As a hobby, he amassed animals during his exotic adventures, and this menagerie became the Zoological Society’s founding collection.

Zoogoers looking at these penguins’ silhouettes might recall the shadowy legacy of captive animal display as a celebration of Victorian triumphalism, offering spectators a taste, an amuse-bouche, of the British Empire’s global conquests. The intent was to persuade the masses that they benefited somehow from the imperial enterprise – that is, “the white man’s burden,” achieving domination and ownership, imposing commercial, cultural, political, and ideological control upon all the world’s different regions and habitats and cultures. The proletariat’s payoff was simply being able to see all these geographically diverse and exotic creatures and bask in the prowess that facilitated the exhibition of such a splendid corpus of animals in the heart of London.

Are the animals actually there at all, or are we just watching shadow-puppets playing out the nostalgic fantasy of imperial control?

© Randy Malamud.

Zoo by Britta Jaschinski is published by Phaidon.

Zoo. Photos: Britta Jaschinski, text: Randy Malamud (1/5)

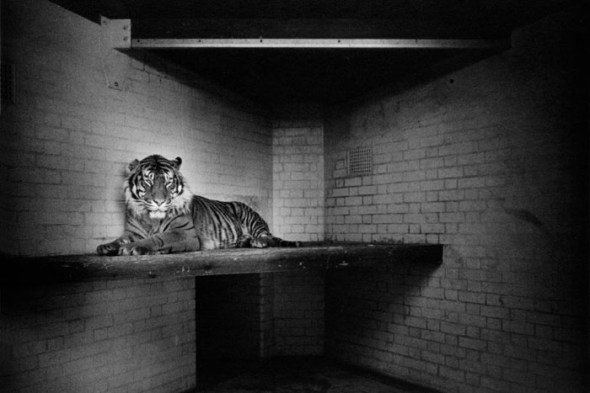

Posted: December 5, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Wildlife | Tags: Sumatran tiger 2 CommentsSumatran Tiger, Zoo Series, London Zoo 1993. © Britta Jaschinski.

Randy Malamud writes:

Britta Jaschinski’s portraits of animals show an insightful expression of the animal’s identity and individuality, an almost devout fascination with the animal’s spirit. But at the same time they resemble mugshots of trapped and unhappy creatures at their worst moments of suffering, caught and fixed in the harsh frame of the image (which is itself metaphorically another cage). They convey loneliness, alienation, displacement. Paradoxically, a single picture may evoke these disparate sensibilities at the same time, both an homage to the animal’s nobility and an angry protest at his constraints.

A photograph of a Sumatran tiger (except it isn’t a Sumatran tiger any longer; now it’s a London tiger) reveals pathos, injustice: the pain of an animal in captivity, The tiger is still, silent, stuck. A pervasive human geometry defines the space. If spectators can infer any sense of emotion or sentience from the creature depicted in a room of sterile white tile, it is resignation, defeat, anomie.

People have a propensity for gawking at subjugated otherness — for example in freak-shows or on reality television — as a way of reaffirming our own supremacy. In the nineteenth century Londoners used to go to Bedlam (St. Mary Bethlehem Hospital) to stare at the lunatics. For a penny one could peer into their cells and laugh at their antics, generally sexual or violent. Entry was free on the first Tuesday of the month. Visitors were permitted to bring long sticks to poke the inmates. In the year 1814, there were 96,000 such visits.

© Randy Malamud.

Zoo by Britta Jaschinski is published by Phaidon.

Ridgers reminisces. Photo & text: Derek Ridgers (1/5)

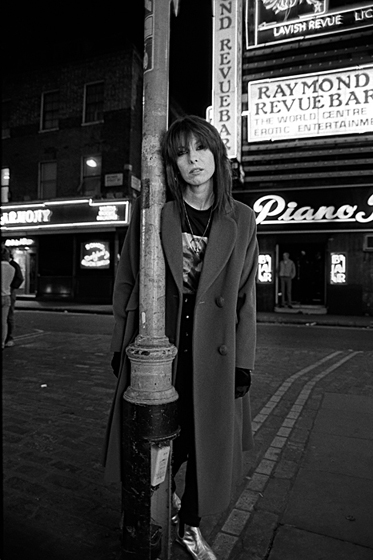

Posted: November 28, 2011 Filed under: Bohemian London, London Music, London Places, London Types | Tags: Cheapo Cheapo, Chrissie Hynde, Nick Kent, NME 1 CommentChrissie Hynde, Soho, 1990. © Derek Ridgers.

Derek Ridgers writes:

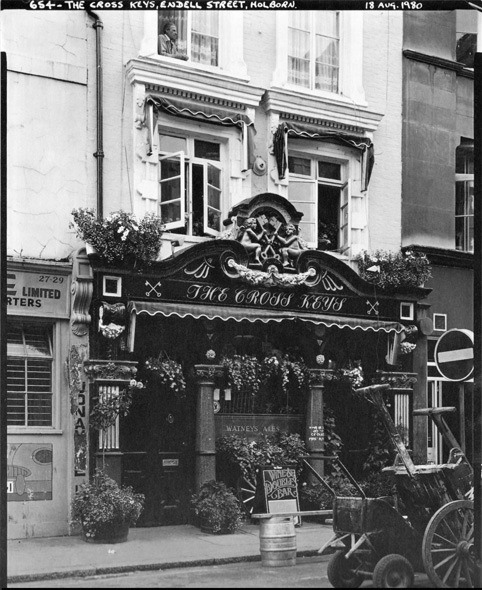

In the late ’70s I was working in an ad agency that was slap bang in the middle of Soho and through the first floor windows of said agency, we had a front seat view of the rich pageant of Soho life only a few feet below. The agency was only about 50 yards away from the passage next to Raymond’s Review Bar and we were able to observe the prostitutes, armed policemen, con men, clip girls, drunks, junkies, glue sniffers and all manner of street people. These types were very thick on the ground in the Soho of the ’70s.

One got very used to seeing some of them. There was one guy I used to see a lot. A dyed-black haired, lanky twerp, normally dressed from head to toe in leather, who obviously thought of himself as some sort of covert rock star. He also wore eye-liner. He always looked totally messed up, emaciated and completely out of it. It was not always an appealing sight. I remember being particularly appalled by seeing the lanky twerp walking through Soho market with his scrotum hanging out of a hole in his trousers. He seemed totally oblivious to this.

Working right in the middle of Soho did have it’s advantages though. My office was a 45 second jog away from the best second hand record shop in the country – Cheapo Cheapo – and every Wednesday morning, at about 11.00 o’clock, the new review copies would arrive and be put straight out into the racks. I was, by this time a voracious reader of both Sounds and NME and my heroes were Charles Shaar Murray, Nick Kent and Danny Baker. I pretty much bought everything they gave a decent review too. So, every Wednesday at exactly 10.55, I’d make an excuse at work and run down to Cheapo Cheapo to buy, at about half the RRP, some of the records that had been favourably reviewed in the previous weeks rock papers. I didn’t realise it at the time but there was every likelihood these were exactly the same copies that had been so reviewed. I’d often see the lanky twerp hanging about Cheapo Cheapo at about the same time as me and I assumed he’d worked out what time the review copies arrived too. I always tried to make sure I got to the best records before he did and, for some strange reason, I always seemed to.

I’d been doing this for a few years during the late ‘70s. Until eventually I got the sack from the agency, became a photographer and I met the NME writer Cynthia Rose. Through her, I got a crack at working for NME myself. One day when we were both hanging about Virgin Records, in Oxford Street, she introduced me to my hero, the writer Nick Kent. And I recognised him as the lanky twerp. The very same lanky twerp that I’d seen rather too much of once before.

(And so it dawned on me that he hadn’t been hanging about Cheapo Cheapo waiting to buy the records but rather selling them the ones I’d subsequently been buying).

The above story is just an excuse to recommend Nick Kent’s fantastic book Apathy For the Devil which is a ’70s memoir of his time as a rock writer and it has some absolutely fantastic stuff about the Rolling Stones, Iggy Pop and the Sex Pistols. It’s just about my favourite rock book since his last one The Dark Stuff. I don’t have a photograph of Nick Kent. But his book has quite a lot about the time when he lived with Chrissie Hynde and so I’ve used a photograph of her. Coincidentally it was taken almost right outside Cheapo Cheapo.

And if you should ever read this Nick, I apologise for once calling you a twerp.

© Derek Ridgers. From The Ponytail Pontifications.