Spitalfields Market. Photo & text: David Secombe.

Posted: October 13, 2011 Filed under: Churches, Literary London, London Places | Tags: east end, Jack London, Thomas Cook Comments Off on Spitalfields Market. Photo & text: David Secombe.Photo © David Secombe 1990.

The opening of Chapter One of People of the Abyss by Jack London, 1902:

“But you can’t do it, you know,” friends said, to whom I applied for assistance in the matter of sinking myself down into the East End of London. […] “Why, it is said there are places where a man’s life isn’t worth tu’pence.” “The very places I wish to see,” I broke in.”But you can’t, you know,” was the unfailing rejoinder.

“Then I shall go to Cook’s,” I announced. “Oh yes,” they said, with relief. “Cook’s will be sure to know.”

“You can’t do it, you know,” said the human emporium of routes and fares at Cook’s Cheapside branch. “It is so – hem – so unusual. […] We are not accustomed to taking travellers to the East End; we receive no call to take them there, and we know nothing whatsoever about the place at all.” “Never mind that,” I interposed, to save myself from being swept out of the office by his flood of negations. “Here’s something you can do for me. I wish you to understand in advance what I intend doing, so that in case of trouble you may be able to identify me.” “Ah, I see! should you be murdered, we would be in position to identify the corpse.” He said it so cheerfully and cold-bloodedly that on the instant I saw my stark and mutilated cadaver stretched upon a slab where cool waters trickle ceaselessly, and him I saw bending over and sadly and patiently identifying it as the body of the insane American who would see the East End.

The photo above was taken twenty-one years ago, and shows homeless people lingering around a bonfire of pallets near the old Spitalfields vegetable market. Hawksmoor’s majestic Christ Church is seen in the distance. Spitalfields used to be cited by ‘psychogeographers’ as one of those London locales where the sad history of the city was engraved upon its streets and buildings: a place that was permanently wrong. The district’s association with poverty, with Jack the Ripper, the waves of the dispossessed that have settled over the centuries – this stuff was meat and drink to the likes of Iain Sinclair and Peter Ackroyd. For his part, Jack London’s attempt to discover the Edwardian East End bore fruit in a book which documented in depressing detail the squalor of Spitalfields, and included photos of down and outs sleeping against the walls of Christ Church. In the 1960s there were moves to demolish the entire area – including Hawksmoor’s church – and the time-locked deprivation of the Georgian district was eloquently pictured by the makers of the film based on Geoffrey Fletcher’s London gazetteer The London Nobody Knows, and by photographers Don McCullin, Paul Trevor and (later) Marketa Luscacova.

My picture dates from a moment just before the wealth and bombast of commercial London annexed the neglected East End. Spitalfields’ desirability as a property market perked up considerably around this time; long-term residents like Gilbert and George, Dan Cruikshank (who had been one of the original squatters who had helped save the area from destruction in the 1970s) and the American artist Dennis Severs, whose house is now a museum, acted as beacons of gentility amidst the inner-city gloom. And, as the 1990s rolled on, the East End went from being the Dark Heart of Old London to Shiny Retail Zone with bewildering speed. I remember laughing at my first sighting of Japanese tourists apparently lost in Shoreditch circa 1997 – but it was, I think, the same year that a Holiday Inn opened on Old Street. A visit to Spitalfields Market today is a trip to Covent Garden East: visitors are safe to purchase their branded goods and speciality coffees in a shopping environment free of disquiet. London Gothic has been displaced by Consumer Bland. It gives the lie to the theories of Ackroyd and Sinclair: with enough commercial pressure, any area, no matter how dark its history, can be transformed into a playground for contented shoppers. Cultural amnesia driven by money. However, given the recent unemployment figures, there may well be opportunities for a resurgence of old-fashioned Victorian deprivation in the East End, although this time it will be hustled to the margins of Whitechapel, Mile End, Barking, etc. D.S.

London Monumental. Photo & text: David Secombe (5/5)

Posted: September 10, 2011 Filed under: London Places, Public Art | Tags: Art Deco, Broadcasting House, Eric Gill, The Tempest Comments Off on London Monumental. Photo & text: David Secombe (5/5)Gill’s Prospero and Ariel, Broadcasting House, 99 Portland Place, W1. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

The artistic legacy of Eric Gill (1882 – 1940) has been irretrievably sullied by the revelations made public in Fiona MacCarthy’s 1988 biography. MacCarthy quoted passages from Gill’s diaries in which he recorded a grotesque catalogue of perversions, including incest with his sister and daughters, as well as a passing liason with the family dog. Gill’s reputation was thus transformed from brilliant bohemian, who fused medieval craftsmanship with modernist practice, to that of a paedophile whose erotic carvings and prints are queasy evidence of a diseased mind.

Many of Gill’s admirers were appalled that MacCarthy had put this knowledge into her book, a sharp contrast to previous biographers who had resolutely ignored the evidence of the diaries. (That MacCarthy was blamed for her act of biographical integrity is appalling in itself.) At any rate, it is no longer possible to survey Gill’s huge output – his many religious carvings in cathedrals and churches, his monuments to the fallen carved in the wake of the First World War, his engravings, even his supremely elegant typefaces (Gill Sans, Perpetua, etc.) – without confronting the upsetting truth about their creator.

There are some fine examples of Gill’s public art in London: in Westminster Cathedral, on 55 Broadway, above St.James’ tube station, and his epic embellishments to the BBC’s flagship headquarters, Broadcasting House in Portland Place. B.H. features a cluster of works by Gill, most prominently his awe-inspiring Prospero and Ariel, two monumental carved stone figures which loom above the main entrance. There are many photographs of Gill working on the statues in situ: dressed in his customary monastic habit (affording passers-by glimpses of his genitals, as he considered underwear an ‘abomination’), Gill resembles a medieval stonemason carving for his God – or, perhaps, an extra who has wandered off the set of a period epic being filmed by Alexander Korda at Denham Studios. Broadcasting House is a sleek hymn to the Moderne set in Portland Stone, a Deco jewel keen to slip its moorings and set sail down Regent Street. And, for all Gill’s avowed medievalism, his sculptures are in keeping with the spirit of the times: Prospero and Ariel look fully at home at the prow of the BBC’s own dry-docked ocean liner.

… for The London Column. © David Secombe 2011.

Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman. (1/3)

Posted: May 17, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Literary London, London on film, London Places | Tags: Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman, Pepys Estate, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman. (1/3)Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo © Tony Ray-Jones/RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Edward Mirzoeff writes:

Bird’s-Eye View was a pioneering series of 13 films shot entirely from a helicopter. For the first of these, The Englishman’s Home (BBC2 5 April 1969) John Betjeman wrote in the commentary about the new high-rise blocks. At the time his strongly-felt views were very much against progressive liberal thinking on the subject, and what he wrote was attacked and derided. By now most people have come round to his old-fashioned but humane way of thinking.

Betjeman refused to fly in the helicopter, but wrote his commentary, in verse, over weeks in the cutting room, once the picture-editing had been completed.

[Edward Mirzoeff was the producer of Bird’s Eye View.]

Pepys Estate, Deptford by John Betjeman:

Where can be the heart that sends a family to the 20th floor

In such a slab as this.

It can’t be right, however fine the view

Over to Greenwich, and the Isle of Dogs.

It can’t be right, caged halfway up the sky

Not knowing your neighbour, frightened of the lift,

And who’ll be in it, and who’s down below

And are the children safe?

What is housing if it’s not a home?”

[Tony Ray-Jones was one of Britain’s finest photographers, whose early death – at just 30 – in 1972 robbed us of an artist of acute insight and integrity. His book A Day Off is celebrated as one of the definitive post-war photographic studies of British life, and influenced a generation of native photographers, not least Martin Parr whose early work showed an obvious debt to Ray-Jones. Until I went searching for means of contacting the Ray-Jones estate, I was unaware of his work for Architectural Review in 1970: a total of 138 pictures that are now in the RIBA photographic library. These are images of the impact of modern housing, and he responded to the brief with characteristic power; he seems to have been especially engaged with the London subjects – Deptford, Thamesmead, the Old Kent Road, etc. – and some of these pictures are the equal of his better-known work. The London Column will be running a further two images from TRJ’s series on the Pepys Estate later this week. Special thanks to Robert Elwall at RIBA Library Photographs for allowing us to reproduce them here. D.S.]

Welcoming smiles … (3/3)

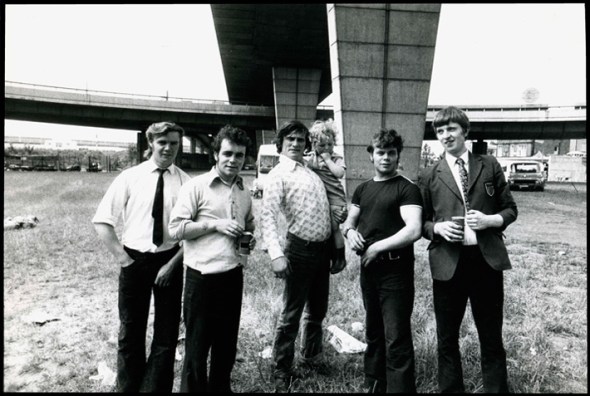

Posted: May 6, 2011 Filed under: London Music, London Places, London Types | Tags: Dave Hendley, Travellers, Westway Comments Off on Welcoming smiles … (3/3)Travellers’ community, Westway. Photo © Dave Hendley 1972.

Dave Hendley writes:

The picture was made one Saturday in the late summer of 1972 at the other end of my working life and in a very different world. I was on a job for Time Out and the mission was to photograph a free music festival in what was then a grassed area under the Westway by Latimer Road. My brief was to photograph stock pictures of musicians for future inclusion in the magazine’s gig guides. The concert was a small and very comfy affair with an audience of around 150 – 200 people.

A short distance away, under what is now the West Cross interchange, there was a cluster of caravans and I spotted a group of traveller men-folk observing the event with curiosity and great amusement.

I wandered over and asked to take a photograph. These were times when being photographed was something of a compliment and the lads posed willingly. I suspect in today’s suspicious climate I would have met with a more hostile reaction. I took just two frames as was my normal procedure back then, film was a precious commodity and consequently I always shot very concisely. After all why would you want more than one or two shots of a particular subject?

Later in the afternoon the Time Out picture editor Rebecca John (the granddaughter of the painter Augustus John) came to say hello and I abandoned my duties for a visit to a nearby pub. Rebecca was a very lovely person and it is is one of my great regrets that we subsequently lost touch over the years.

I returned to photograph a few more bands, including a musician called Steve Hillage, a strange hippie type in a pixie hat. As I was shooting away a scruffy but very polite and gently spoken young man approached me and enquired if he could buy some pictures. He wrote his name, Richard, and contact details on the back of a crumpled flyer. On the following Monday I made my way to the Virgin shop in Notting Hill Gate where I sold Richard Branson a couple of frames for a tenner.

© Dave Hendley 2011