London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (4/5)

Posted: July 5, 2012 Filed under: Pubs, The Thames, Vanishings | Tags: Dickens, J.G. Ballard, joggers of Wapping, our mutual friend, Town of Ramsgate, Wapping High Street, Wapping Old Stairs Comments Off on London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (4/5)Town of Ramsgate pub, Wapping Old Stairs. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

From Unknown London, W.G. Bell, 1919:

Wapping High Street in the days of Nelson’s wars possessed upwards of one hundred and forty ale-houses. In a recent perambulation I was not able to count ten. Together with these reeking drink shops, inexpressible in their squalor and dirt, were other houses of resort which one may deftly pass by without too curious enquiry. In the gloomy slum area at the back, the inner recesses of the hive, mostly dwelt the people who lived, quite literally upon the sailor, and they formed the greater part of the population that was herded here. Every tavern kept open door to welcome the mariner with wages in his pocket.

You may land at the Old Stairs still … The ‘Town of Ramsgate’ stands at the head of the Stairs, where it has stood these past two centuries or more for the refreshment of sailors. Wapping was the busiest centre of the seafaring life of the port of London. Of the many landing-places, the deserted Old Stairs and the New Stairs, nearer the City, alone survive. And you may tramp Wapping from end to end without recognizing a sailor man.

David Secombe:

Nearly a hundred years later, Bell’s assessment of Wapping remains valid, although these days the eeriness of its riverside enclave has a particularly 21st Century quality. Wapping High Street’s narrow pavements teem with joggers: driven young (or young-ish) men and women who appear from nowhere, pounding behind you silently before speeding past towards … what? Apart from the joggers, you may see a few tourists who make the journey to visit the pubs and riverside sights, and it is undeniably true that at certain times (dusk in November, for example) the environs of Wapping Old Stairs retain an impressive atmosphere: catnip for Dickens-fanciers armed with much-thumbed copies of Our Mutual Friend. However, in cold, hard daylight, the perfectly made-over warehouses and tastefully integrated new-build developments dispel memories of Dickens and recall instead the preoccupations of a more modern London writer: J.G. Ballard. Modern Wapping could be a starting point for one of his forensic studies of fear within insular communities, wherein the hot-house social conditions unleash perversity and violence behind the security gates of the ‘executive development’. In the 1970s, he set such a dystopia downriver, in a tower block that might have been designed by Erno Goldfinger (High Rise); but the make-over of ‘heritage’ environments, the loading-bays transformed into penthouses, offers a more contemporary setting for a Ballardian nightmare.

Ultimately, perhaps, the unnerving quality riverside Wapping possesses today is that of a ghost seen walking in the noonday sun: the ghost of London.

… for The London Column.

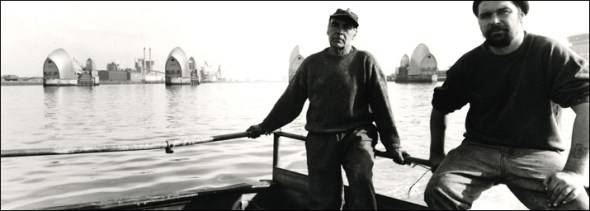

Flotsam and jetsam. Photo & text David Secombe. (2/5)

Posted: April 17, 2012 Filed under: Amusements, Artistic London, The Thames, Transport | Tags: Britart, commercial Thames, corporate London, Damien Hirst, Spot paintings, Tate Boat, Tate Britain, Tate Modern, tate to tate 1 CommentThe Thames, looking east from Hungerford Bridge, 2010. Photo © David Secombe.

From Tate Online : 1 May 2003:

From 23 May Tate to Tate, a new boat service on the river Thames, will be available for gallery lovers. The service, which runs every forty minutes during gallery opening hours between Tate Modern and Tate Britain, will be launched on 22 May by The Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone. The boat also stops at the London Eye.

The Tate to Tate boat service, operated by Thames Clippers, is a state-of-the art 220 seat catamaran with specially commissioned exterior and interior designs by leading artist Damien Hirst. The boat is sponsored by St James Homes, a property developer.

David Secombe writes:

Now that Damien Hirst is the richest artist in the world (proof if any were needed of the global success of that strange London-based phenomenon known as ‘BritArt’), it seems entirely fitting that ‘the fastest’ commercial vessel on the Thames, ferrying passengers to and from the world’s most popular – some might say populist – art gallery, bears one of his patented designs. The Tate boat is decorated with Hirst’s bright, multi-coloured dots, and travels between those twin bastions of culture, Tate Modern and Tate Britain – the former fashioned from a derelict power station, the latter built on the site of a penitentiary.

For good or ill, Hirst seems to be the artist who best embodies his time; one can’t imagine a Bacon Barge or a Rothko Raft, whereas our Damien’s spotty pleasure cruiser – made possible by a property consortium – seems completely, depressingly, apt.

(The London Column has not yet felt the siren call of the current Hirst exhibition at the Tate, but you can read a response to the Sotheby’s extravaganza of 2008 on Baroque in Hackney. For another view of Hirst and his influences, see: http://www.stuckism.com/Hirst/StoleArt.html.)