Hawksmoor and the city.

Posted: February 18, 2016 Filed under: Architectural, Churches, Dereliction, Monumental, Pavements, Street Portraits | Tags: Ackroyd's Hawksmoor, Christopher Wren's London, Hawksmoor churches, Nicholas Hawksmoor, Owen Hopkins Comments Off on Hawksmoor and the city.

Christ Church Spitalfields from Brushfield St., 1990. (This and all photos on this page © David Secombe.)

Owen Hopkins:

Ever since they began to rise over London just over 300 years ago, the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor (1662–1736) have had an ambiguous – even paradoxical – relationship to the city that made them and which they have in turn remade. On the one hand, the churches of St Anne, Limehouse, Christ Church, Spitalfields and St George-in-the-East in the old parish of Stepney, St. Alfege in Greenwich, St Mary Woolnoth in the City of London and St George, Bloomsbury are inextricably bound up with the history of London. On the other, they stand apart, somehow belonging to a rather different time and place, almost as fragments of Ancient Rome transplanted into London.

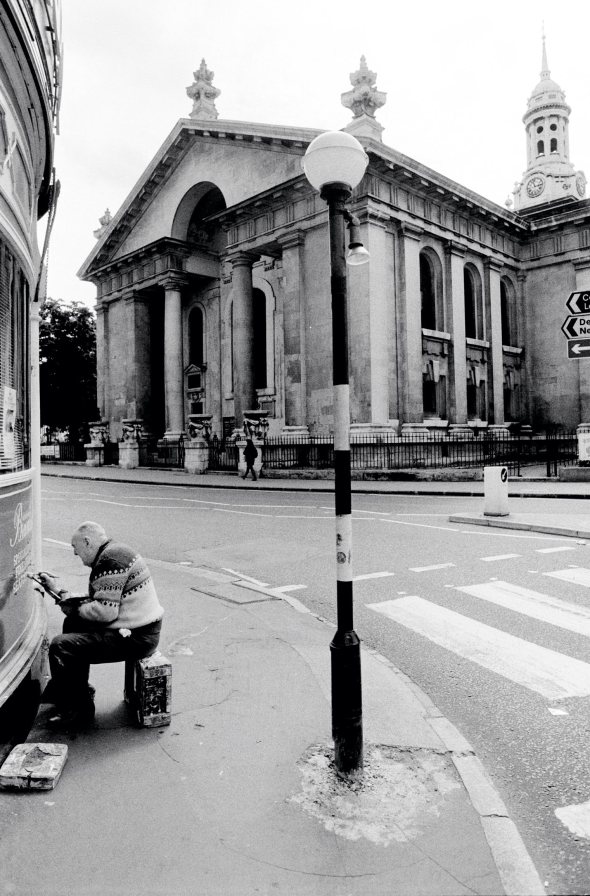

St Alfege, Greenwich, 1988.

St Alfege, Greenwich, 1988.

To understand Hawksmoor’s churches and their relationship to the city, one has to go back to the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1666. Even as the fire still smouldered, Hawksmoor’s later master, Christopher Wren, was working up a plan for London’s rebuilding that would replace its narrow and irregular medieval streets with grand boulevards. Most importantly, and taking direct inspiration from what he had learned in Paris the year before, Wren’s plan would have imposed a clear spatial order and control on the dangerous and unruly metropolis.

Hawksmoor’s approach to city planning was different. Hawksmoor never created a plan for London in the way his master had done, but he did produce (unbuilt) designs for re-planning Oxford and Cambridge, and parts of London around St Paul’s Cathedral, Greenwich, and Westminster. The easiest way to understand how these would have worked is to look to contemporary landscape gardens: manufactured landscapes littered with classically-inspired temples and follies, structures that dominate the vistas and embody the estate owner’s authority.

St George-in-the-East, Wapping, 2010.

St George-in-the-East, Wapping, 2010.

Similarly, in Hawksmoor’s idea of the city, spatial order and control extended not from the street layout, but from monumental buildings that would physically dominate their surroundings. In all Hawksmoor city plans we see a recurring strategy of clearing the areas around important buildings – both old and new – so that they might express their spatial dominion over the surrounding cityscape. What happened in between was of far less importance. It’s hard to imagine the effect of these unbuilt plans when described in the abstract, but to see their principles in action we only need look as far as Hawksmoor’s churches.

St Luke’s Old St. (Hawksmoor & John James), photographed before its 21st century restoration, 1988.

St Luke’s Old St. (Hawksmoor & John James), photographed before its 21st century restoration, 1988.

Even now, the areas around Hawksmoor’s three churches in the old parish of Stepney still retain the ‘edge-lands’ feel they must have had when they first grew up in the decades following the Great Fire. Today that energy is manifested in the clash of different cultures and economies as the City of London encroaches on East End communities. In the early eighteenth century the energy arose through the rise of dissenting religious groups, outside the orbit of central Anglican control, with all the social and political ramifications that that held. As a result, Hawksmoor’s churches were conceived from the off as outlying beacons of the city’s spiritual and political centre – monuments of state and Church authority in areas that had none.

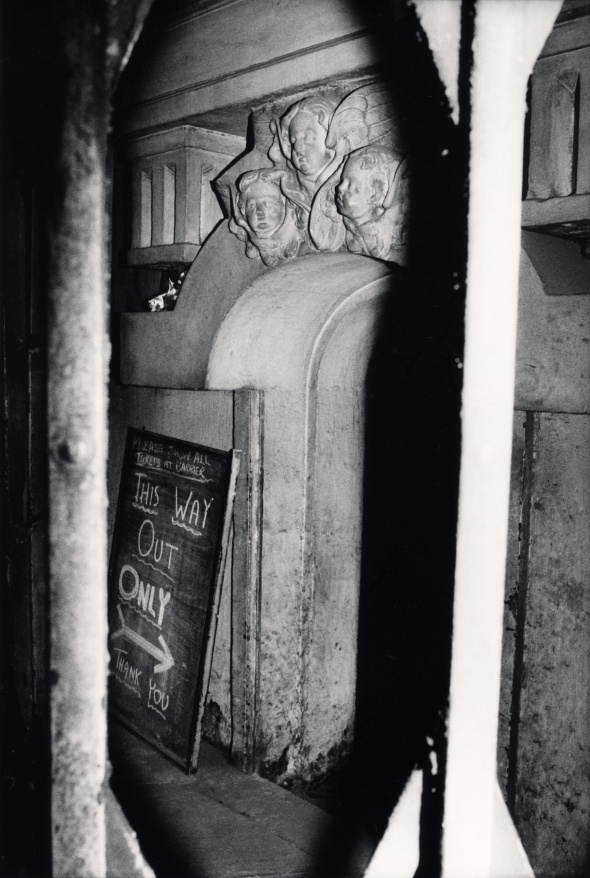

Entrance to Bank tube station showing part of the crypt of St Mary Woolnoth, City of London, 1988.

Entrance to Bank tube station showing part of the crypt of St Mary Woolnoth, City of London, 1988.

All three of Hawksmoor’s Stepney churches are colossal structures, deliberately sited to be seen in the round, that dominate their environment by sheer scale. Not surprisingly, their overbearing size has played a part in their subsequent neglect. In a 1975 letter to The Times, the then Bishop of Stepney, Trevor Huddlestone, was at great pains ‘to make it clear that the state of disrepair of Christchurch, Spitalfields is in no sense due to the failure of the local Christian community, nor, in my opinion, to neglect by the authorities of the Church of England’. Such a building of ‘cathedral-like proportions’ was, he argued, an ‘appalling responsibility for the Church’.

In addition to their size, Hawksmoor was able to make his churches stand out by his choice of material: white Portland stone, as opposed to the red brick of the surrounding city. Hawksmoor’s churches appear as if fully formed from a single gigantic block of stone. There’s the sense that this is the form the stone wants to be – a testament to their design, the final and most enduring aspect of their differentiation from the surrounding city.

St Anne’s Limehouse, 2010.

St Anne’s Limehouse, 2010.

Having risen up through Wren’s office in the 1680s and 90s, by the beginning of the eighteenth century Hawksmoor was arguably the best-trained architect Britain had ever seen. Classical architecture was his intellectual and aesthetic bedrock, but he was also fascinated by Gothic architecture and in particular its origins – as he saw them – in the churches of the early Christians of the near east. Hawksmoor’s genius was to bring all this learning to bear in creating a series of church designs rich in reference, resonance and allusion. The result was a series of buildings in which architecture was taken back to its very origins, with ideas and references built up in complex layers of masonry, imbuing these structures with the authority of the architectural past. This is architecture conceived through a sculptural sensibility to create buildings that speak to us but indirectly: through our senses and our emotions.

St George Bloomsbury, 2016.

St George Bloomsbury, 2016.

There are few buildings in London that look back to the past while at the same time prefigure the future. While part of London’s history, Hawksmoor’s churches exist in the future too, yielding ever more secrets as the city changes around them.

… for The London Column. Owen Hopkins’s book From The Shadows: The Architecture and Afterlife of Nicholas Hawksmoor is published by Reaktion Books.

© Owen Hopkins. All photos © David Secombe.

See also: Bluegate Fields, The London Nobody Knows, Spitalfields market.

Ten Old Men.

Posted: May 27, 2014 Filed under: Eating places, London Types, Pavements, Shops, Street Portraits, Transport | Tags: bowls, David Secombe, Kings Cross, old geezers, outdoor chess, Tim Marshall, Victoria Way, Woolwich Comments Off on Ten Old Men. Woolwich. © David Secombe 1998.

Woolwich. © David Secombe 1998.

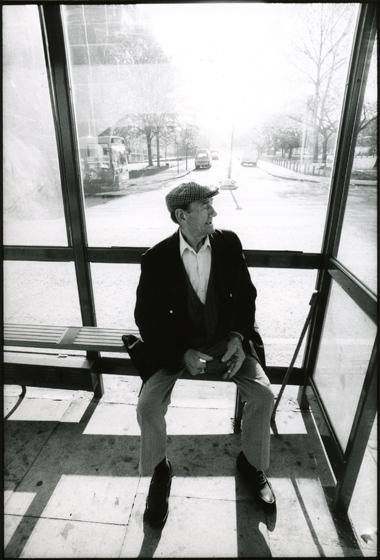

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

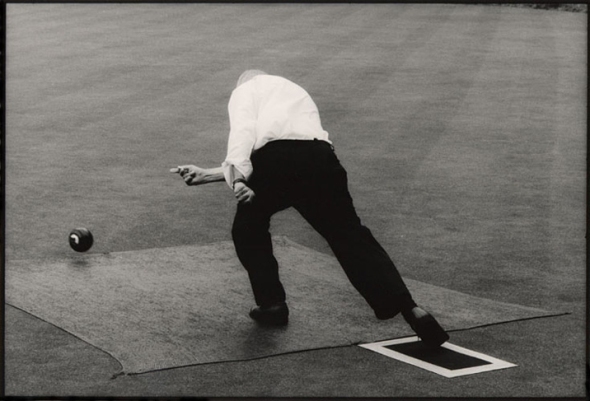

Finsbury Circus. © David Secombe 1998.

Finsbury Circus. © David Secombe 1998.

Clapham Common. © David Secombe 1998.

Clapham Common. © David Secombe 1998.

Spitalfields Market. © David Secombe 1990.

Spitalfields Market. © David Secombe 1990.

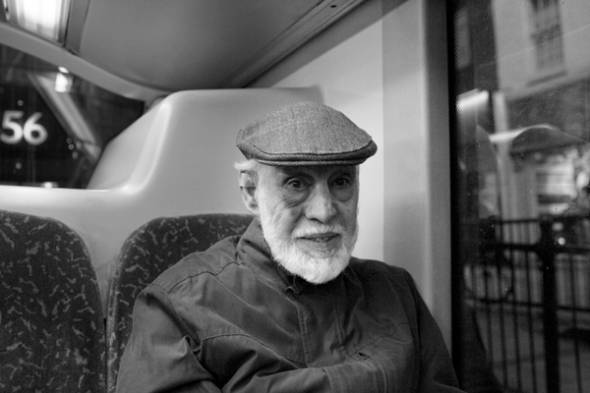

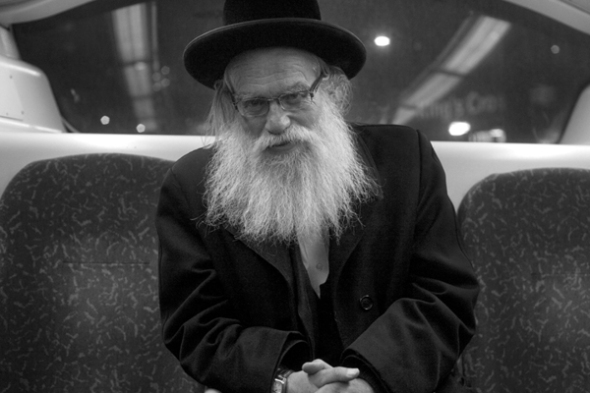

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

Charlton. © David Secombe 1997.

Charlton. © David Secombe 1997.

See also: 38 Special, King’s Cross Stories, Underground, Overground, Deep South London, Spitalfields Market, Park Life, Ten Imperatives.

East Ender.

Posted: October 21, 2013 Filed under: Eating places, Graffiti, Health and welfare, Lettering, London Labour, Markets, Public Art, Street Portraits | Tags: Hoxton, Hoxton Mini Press, Joseph Markovitch, Martin Usborne, old East End 2 Comments© Martin Usborne.

Joseph Markovitch:

I was born right by Old Street roundabout on January 1st, 1927. Some of the kids used to beat me up – but in a friendly way. Hoxton was full of characters in those days. The Mayor was called Mr. Brooks and he was also a chimney sweep. Guess what? Before the coronation, he was putting up decorations and he fell off a ladder and got killed. Well, it happens. Then there was a six-foot tall girl, she was really massive. She used to attack people and put them in police vans. Maria was her name. Then there was Brotsky who used to kill chickens with a long stick. His son’s name was Monty. That’s not a common one is it? ‘Monty Brotsky’.

© Martin Usborne

I worked two years as a cabinet maker in Hemsworth Street just off Hoxton market. But when my sinuses got bad I went to Hackney Road putting rivets on luggage cases. For about twenty years I did that job. My foreman was a bastard. Apart from that it was OK. But if I was clever, very clever, then I would have liked to be an accountant. It’s a very good job. And if I was less heavy … you know what I’d like to be? I’d like to be a ballet dancer. That would be my dream.

© Martin Usborne

I don’t mind people taking pictures of me. But I wouldn’t let a girl take a picture of me. She might have a boyfriend. I don’t want any trouble. And who knows, he might think she wants to run off with me. You got to be careful where you go nowadays. Martin, if you want to take this picture you had better be quick. I don’t take a good picture when my bladder is full.

© Martin Usborne

If I try, I can imagine the future. It’s like watching a film. Pavements will move, nurses will be robots and cars will get smaller and grow wings … you’ve just got to wait. They will make photographs that talk. You will look at a picture of me and you will hear me say: ‘Hello I’m Jospeph Markovitch’ and then it will be me telling you abut things. Imagine that! I also have an idea that in about fifty years Hoxton Square will have a new market with an amazing plastic rain cover. So if it rains the potatoes won’t get wet. I don’t know what else they will sell. Maybe bowler hats. Nothing much changes round here in the end.

© Martin Usborne.

There’s no point crying about things is there? People don’t see you when you’re sad. Best just to keep walking.

Do you know that I can’t eat lettuce? I’ve got no teeth, not for ten years. It’s hard to like lettuce if you haven’t got teeth.

… taken from I’ve Lived In East London for 86.5 Years, photographs by Martin Usborne, the debut publication of Hoxton Mini Press. More details may be found on their Kickstarter page.

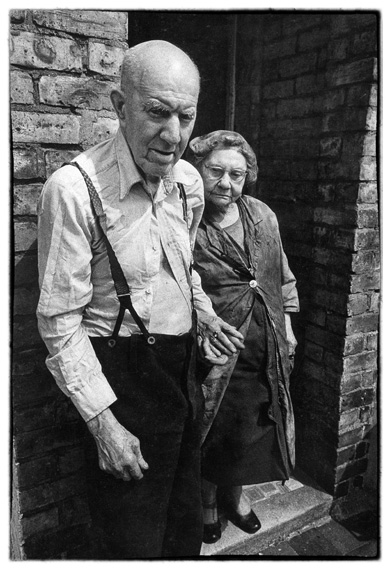

Old couple facing eviction. Photo: Dave Hendley, text: David Secombe.

Posted: November 16, 2012 Filed under: Housing, Street Portraits | Tags: Dave Hendley, Digital Gap, Fulham eviction Comments Off on Old couple facing eviction. Photo: Dave Hendley, text: David Secombe.Overheard pub conversation:

Everyone’s got an uncle Bill. And everyone’s got just one picture of him. Uncle Bill died before you were born. The photo is your mum’s, taken on a trip to Hayling Island when she was a girl. And she shows you this photo, a tear at the corner of her eye, ‘That’s your Uncle Bill’ she says. And she hands you a tiny black and white picture of a man in a suit standing in the middle of a field. That’s your Uncle Bill. Well, it was my Uncle Bill. Who was called Norman. Your Uncle Bill was probably called Cliff. Or Lance.

In the final of the series of Dave Hendley’s rediscovered 1970s photos, this image shows an elderly couple outside their house in Fulham; they were facing eviction from their home after living there for decades. That is as much as I can tell you about the facts of the picture; Dave doesn’t know what became of them or the house itself (if it wasn’t flattened for redevelopment, it is probably now one of those candy-coloured terraced houses that go for over a million pounds). I’d like to know the full story, but perhaps it’s as well I don’t. I imagine the outcome was shabby and depressing: the early 1970s was not a glorious era for social housing in London.

Dave’s photographs this week are fragments of a lost career, and these pictures only exist because he left some old prints at his mother’s house. I don’t know why Dave felt compelled to chuck his old negatives, but he was young when he did it and perhaps didn’t reckon on their value as a permanent record. Now that almost all photographs exist as pixellated images that never get preserved as hard copy, it is sobering to consider the implications for the future. Dave ditched his negatives and got old enough to regret it, but fine prints were (accidentally) preserved. Today’s toy-like cameras make images that are no more durable than an ice sculpture. Photography is becoming utterly ephemeral: you aren’t creating a graven image, you are generating a string of code. Then, a bit later, maybe you get short of space on a memory card so you ditch a few images you don’t think you’ll need, or you forget to back them up, or the hard drive they were on went down … you won’t recover those pictures in anyone’s attic, they are gone. The future is bright and shiny and cares not for the past. Even those of us still using film wince at the price of ‘traditional’ materials: posterity carries a premium. What did Uncle Bill look like again?