Flotsam and jetsam. Photo and text David Secombe (3/5)

Posted: April 18, 2012 Filed under: Bohemian London, Entertainment, The Thames and its Tributaries, Vanishings | Tags: Freddie Mercury's cake, malcolm hardee, Tunnel Palladium Comments Off on Flotsam and jetsam. Photo and text David Secombe (3/5)Blackwall Tunnel southern approach, SE10, 1997. Photo © David Secombe.

David Secombe writes:

The mock-Tudor building in front of the gas holder in the picture above is the former home of the 1980s comedy club The Tunnel Palladium, so called because the building sits only a few yards way from the mouth of the southern entrance to the Blackwall Tunnel. The club was run by the legendary local comic and promoter Malcolm Hardee, and it played host to many key figures in the alternative comedy circuit at the start of their careers.

Amongst the legions of anecdotes concerning Malcolm Hardee, three are worth retelling here . . .

1) At the 1983 Edinburgh Fringe, he became annoyed by excessive noise from an adjacent comedy tent where Eric Bogosian was performing, and retaliated by stealing a tractor and driving it, naked, across Bogosian’s stage during his performance.

2) He stole Freddie Mercury’s 40th birthday cake and gave it to an old people’s home.

3) He pioneered a stage routine (later taken up by Chris Lynam) in which the performer sings There’s No Business like Show Business whilst holding a lit firework between his buttocks.

Malcolm Hardee died in January 2005, drowning in Greenland Dock, where his houseboat was moored; the Coroner’s verdict was that he had fallen into the dock whilst drunk. According to the police constable who retrieved Malcolm’s body from the water, he was found still clutching a bottle of beer in his right hand.

… for The London Column.

Ridgers reminisces. Photo & text: Derek Ridgers (3/5)

Posted: November 30, 2011 Filed under: Bohemian London, Clubs, London Types | Tags: Fetish, Skin Two, Torture Garden Comments Off on Ridgers reminisces. Photo & text: Derek Ridgers (3/5)Ann-Sophie and Jenni, The Torture Garden, London, 2010. © Derek Ridgers.

Derek Ridgers writes:

I’ve been taking photographs in London fetish clubs since 1981. And the occasional fetishist in other clubs since about 1978.

To the best of my knowledge, the popularity of fetishism really started in the UK in 1976 with the emergence of punk rock and the appropriation of elements of bondage and fetish wear by many of the punk era designers. Prior to this time, people who wanted to dress in rubber and PVC had to do it behind closed doors, ordering their outfits by mail-order in brown paper parcels.

To begin with it was just a handful of people in a small dingy Soho club called Skin Two, which resided in what was, the rest of the week, a gay club called Stallions. Skin Two was started by an actor called David Claridge. He went on to become famous as the hand up the furry arse of TV star ‘Roland Rat’ and after his nocturnal predilections were exposed by the gutter press, he disappeared from the scene. The atmosphere in the Skin Two club was oppressive and sometimes menacing. Outsiders, especially ones with cameras, were certainly not made to feel welcome. But, pretty soon, big name photographers like Bob Carlos Clarke and several others brought fetish style images into view more and things got a lot more relaxed.

By the mid-’80s PVC and rubberwear was all over fashion magazines and pop videos. By the late ’80s/early ’90s some of the bigger fetish clubs like Submission and Torture Garden could easily attract 3000 people a night and people came from all over the world to get there. And then some of them went back home and started their own fetish clubs. Nowadays, Torture Garden has become very mainstream and it’s not completely unlike any other large club in any other major western city, except sometimes people are dressed very oddly.

In the early days, I got threatened with physical violence in Skin Two several times. One guy seized me by the neck and we nearly came to blows. A couple of women grabbed me one night and tried to drag me over to where one of the dominatrixes was waiting, whip in hand. I had to manhandle them off me and make my getaway. But I was clearly an outsider back then and I would never have even gotten into the early fetish clubs if I hadn’t become friendly with some of the people running them. I know for a fact that most of the old-time fetishists resented my presence. But it was obviously people like me that helped to publicise and promote the scene, so the people who ran the clubs have always been very welcoming. These days you can’t move for photographers in these kind of clubs.

I’m not really sure what it was about the fetish scene that appealed to me. I’m not a fetishist myself and don’t even really like wearing the leather trousers I’m obliged to wear in these clubs. To begin with I had a real compulsion to photograph the way people were dressing and the amount of humour and invention some people put into creating their own, largely home-made, outfits was certainly worth somebody recording. These days, most people in fetish clubs are wearing shop bought, off-the-peg outfits but there are still many remarkable individualists.

Nevertheless, some people say that there’s something badly wrong with any man over 30 who still wears leather trousers, whatever the excuse. In my case, they’re probably right. Exactly what that something “wrong” might be, I’ll leave you to draw you own conclusions.

Anyone who wants to know more about the fetish scene could do a lot worse than go here – http://www.thefetishistas.com/

© Derek Ridgers. From The Ponytail Pontifications.

Ridgers reminisces. Photo & text: Derek Ridgers (1/5)

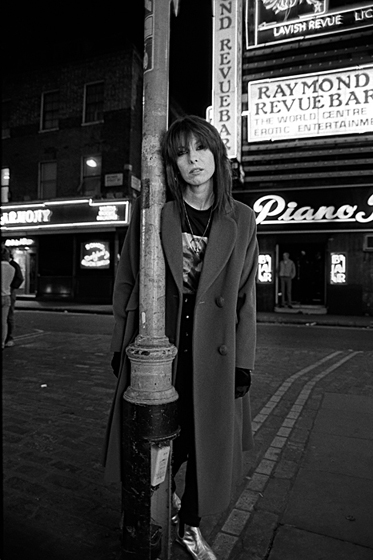

Posted: November 28, 2011 Filed under: Bohemian London, London Music, London Places, London Types | Tags: Cheapo Cheapo, Chrissie Hynde, Nick Kent, NME 1 CommentChrissie Hynde, Soho, 1990. © Derek Ridgers.

Derek Ridgers writes:

In the late ’70s I was working in an ad agency that was slap bang in the middle of Soho and through the first floor windows of said agency, we had a front seat view of the rich pageant of Soho life only a few feet below. The agency was only about 50 yards away from the passage next to Raymond’s Review Bar and we were able to observe the prostitutes, armed policemen, con men, clip girls, drunks, junkies, glue sniffers and all manner of street people. These types were very thick on the ground in the Soho of the ’70s.

One got very used to seeing some of them. There was one guy I used to see a lot. A dyed-black haired, lanky twerp, normally dressed from head to toe in leather, who obviously thought of himself as some sort of covert rock star. He also wore eye-liner. He always looked totally messed up, emaciated and completely out of it. It was not always an appealing sight. I remember being particularly appalled by seeing the lanky twerp walking through Soho market with his scrotum hanging out of a hole in his trousers. He seemed totally oblivious to this.

Working right in the middle of Soho did have it’s advantages though. My office was a 45 second jog away from the best second hand record shop in the country – Cheapo Cheapo – and every Wednesday morning, at about 11.00 o’clock, the new review copies would arrive and be put straight out into the racks. I was, by this time a voracious reader of both Sounds and NME and my heroes were Charles Shaar Murray, Nick Kent and Danny Baker. I pretty much bought everything they gave a decent review too. So, every Wednesday at exactly 10.55, I’d make an excuse at work and run down to Cheapo Cheapo to buy, at about half the RRP, some of the records that had been favourably reviewed in the previous weeks rock papers. I didn’t realise it at the time but there was every likelihood these were exactly the same copies that had been so reviewed. I’d often see the lanky twerp hanging about Cheapo Cheapo at about the same time as me and I assumed he’d worked out what time the review copies arrived too. I always tried to make sure I got to the best records before he did and, for some strange reason, I always seemed to.

I’d been doing this for a few years during the late ‘70s. Until eventually I got the sack from the agency, became a photographer and I met the NME writer Cynthia Rose. Through her, I got a crack at working for NME myself. One day when we were both hanging about Virgin Records, in Oxford Street, she introduced me to my hero, the writer Nick Kent. And I recognised him as the lanky twerp. The very same lanky twerp that I’d seen rather too much of once before.

(And so it dawned on me that he hadn’t been hanging about Cheapo Cheapo waiting to buy the records but rather selling them the ones I’d subsequently been buying).

The above story is just an excuse to recommend Nick Kent’s fantastic book Apathy For the Devil which is a ’70s memoir of his time as a rock writer and it has some absolutely fantastic stuff about the Rolling Stones, Iggy Pop and the Sex Pistols. It’s just about my favourite rock book since his last one The Dark Stuff. I don’t have a photograph of Nick Kent. But his book has quite a lot about the time when he lived with Chrissie Hynde and so I’ve used a photograph of her. Coincidentally it was taken almost right outside Cheapo Cheapo.

And if you should ever read this Nick, I apologise for once calling you a twerp.

© Derek Ridgers. From The Ponytail Pontifications.