Arthur Machen’s Hill of Dreams.

Posted: July 4, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Bohemian London, Fictional London, Literary London | Tags: Arthur Machen, Battersea, Hill of Dreams, pipe smoker Comments Off on Arthur Machen’s Hill of Dreams.Tennyson Street, Battersea. Photo © David Secombe 1982.

From Hill of Dreams, Arthur Machen, 1907:

It was not till the winter was well advanced that he began at all to explore the region in which he lived. Soon after his arrival in the grey street he had taken one or two vague walks, hardly noticing where he went or what he saw; but for all the summer he had shut himself in his room, beholding nothing but the form and colour of words. [. . .]

Now, however, when the new year was beginning its dull days, he began to diverge occasionally to right and left, sometimes eating his luncheon in odd corners, in the bulging parlours of eighteenth-century taverns, that still fronted the surging sea of modern streets, or perhaps in brand new “publics” on the broken borders of the brickfields, smelling of the clay from which they had swollen. He found waste by-places behind railway embankments where he could smoke his pipe sheltered from the wind; sometimes there was a wooden fence by an old pear-orchard where he sat and gazed at the wet desolation of the market-gardens, munching a few currant biscuits by way of dinner. As he went farther afield a sense of immensity slowly grew upon him; it was as if, from the little island of his room, that one friendly place, he pushed out into the grey unknown, into a city that for him was uninhabited as the desert.

At 11.30 a.m. (UK) today, Thursday 4 July, Radio 4 is broadcasting a documentary about Arthur Machen and his ‘disturbing’ visions of a world beyond our own.

Calling at the Albany to see Graham Greene.

Posted: May 21, 2013 Filed under: Fictional London, Literary London | Tags: Albany, Dmitri Kasterine, Graham Greene, The Comedians 1 CommentGraham Greene, Antibes. © Dmitri Kasterine 1983.

Expedition to Greeneland by Susan Grindley

There was a problem with the spellings

of Yeastrol, or Yeastrel, and Tontons Macoutes.

I was the office junior, despatched

with marked-up galley proofs to Albany.

I washed and ironed my hair the night before,

wore my shift dress from Peter Robinson’s

new Top Shop with white stockings and white

patent shoes from Elliott’s of Bond Street.

I’d cracked the secret code to all his books –

women who thought that they were loved were not.

He kept them parked and waiting in the margins,

all that religious stuff – just an excuse.

I didn’t see him. I just left the envelope

with the top-hatted porter at the lodge.

I told them casually back at Production,

‘GG is lunching at his club today.’

© Susan Grindley. The poem is from Susan’s collection New Reader, published by Rack Press; also available from Waterstones, and The London Review Bookshop, 14 Bury Place, London, WC1A.

A Clockwork London. (2)

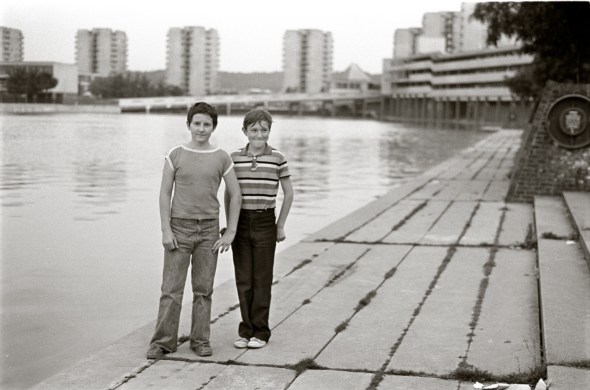

Posted: April 4, 2013 Filed under: Fictional London, Housing, London on film | Tags: A Clockwork Orange, Binsey Walk, Bird's Eye View, George Plemper, John Betjeman, Owen Hatherley, Stanley Kubrick, Thamesmead 1 CommentSouthmere Lake and Binsey Walk, Thamesmead. © George Plemper 1976.

George Plemper:

In late 1972 I made the journey to Leicester Square to see A Clockwork Orange. As with all Kubrick’s

films I thought the film was visually stunning and I loved the use of music throughout. The physical

and sexual violence seemed to me more theatrical than factual and I was astonished to hear a year

later the film had been banned.

All thoughts of the film had long gone when I crossed the footbridge across Yarnton Way

to Riverside School, Thamesmead in 1976. I had no idea I was entering a scene from Kubrick’s vision

of a desolate and violent Britain. My aims were simple; I was going to use the camera to show my

pupils that they were great, to show them that we were all worthwhile.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain by Owen Hatherley:

It’s impossible to praise the original Thamesmead without caveats. There were never enough facilities, the transport links to the centre were always appalling, and the development was always shockingly urban for its outer-suburban context. Regardless, it is something special, a truly unique place. It always was, and remains so in its current, amputated form.

Unlike its successors, it’s flood-proof and still architecturally cohesive, after decades of abuse. Around Southmere lake you can see, just about, how with some decent upkeep and with tenants being given the choice rather than being dumped here, this could have been a fantastic place … This is basically a working-class Barbican, and if it were in EC1 rather than SE28 the price of a flat would be astronomical. Today it feels beaten and downcast, and it only ever gets into the news through vaguely racist stories about the Nigerian fraudsters apparently based here; but its architectural imagination, civic coherence and thoughtful detail, its nature reserves and wild birds, have everything that the ‘luxury flats’ lack.

Southmere Lake and Binsey Walk today. © David Secombe 2013.

Where Alex walked … watch him pitch his droogs into the cold, cold waters of Southmere Lake here.

See also: Pepys Estate 1, Pepys Estate 2, Domeland, Metro-Land.

Metro-Land.

Posted: January 10, 2013 Filed under: Architectural, Fictional London, Housing, Literary London, Meteorological, Transport | Tags: Art Deco, Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman, Metroland, Metropolitan Line 1 CommentPinner Station at dusk. © David Secombe 2011.

From Murder at Deviation Junction by Andrew Martin*:

‘Londoner,’ said Bowman, shaking his head, ‘born in some tedious spot like … I don’t know… Pinner’.

From Pennies from Heaven by Dennis Potter:

ACCORDION MAN: We’re all going to hell. We’re all going to burn in hell. Thank you very, very much, sir. Thank you very, very much, madam. Thank you very, very much, sir.

David Secombe:

Today marks the 150th birthday of The Tube – and for The London Column’s modest contribution to this anniversary I would like to draw our readers’ attention to the BBC4 repeat at 10 pm tonight of TLC contributor Edward Mirzoeff’s classic 1973 documentary Metro-Land, written and presented by John Betjeman. For anyone that hasn’t seen it, this film is a glorious relic of the golden age of the British television documentary, and takes as its subject the early 20th Century suburbs that grew up alongside the Metropolitan Line as it extended deep into rural Middlesex. As the poet laureate of inter-war suburbia and the Met line in particular, Betjeman is the ideal tour guide for this trip from Baker Street to Neasden, Wembley, Harrow, Pinner and beyond.

Pinner is the quintessence of inter-war residential development: serried rows of polite, cheerful villas and semi-detached houses spreading outwards from the remnants of an ancient hamlet. So whilst Pinner Village contains some very old houses indeed, the Metropolitan Line is the reason we are here: Met Line trains from Pinner station take just 25 minutes to reach Baker Street. Pinner’s tidy crescents and avenues were intended as havens from the dirt and clamour of the city – with desirable residences, clean air, the Met Line to take you into town, and the shops and cinema of the new parade just a few steps away, what more could life offer? Naturally, Metro-Land’s quasi-rural calm came at the expense of Middlesex’s actual rural landscape, which entirely disappeared beneath the streamlined semis, but this is a very English approach to Moderne living (as opposed to Modernism, which the British didn’t exactly take to their hearts) – tidy, domesticated, and hungry for acreage. Metro-Land is not so much a place as a state of mind, a dream of what life might be; a bucolic idyll with all the benefits that the Tube, the ring roads, the wireless and state-of-the-art plumbing could bring.

But the near-identical streets of Pinner, Eastcote, Ruislip, Rayners Lane and their neighbours are also an expression of a state of unease. The cosy, complacent sprawl of these suburbs comes at a price. The new suburban landscape goaded and inspired Betjeman (‘Your lives were good and more secure/Than ours at cocktail time in Pinner’), as it did George Orwell (Coming up for Air), Louis MacNeice ( ‘But the home is still a sanctum under the pelmets’), Graham Greene (‘a sinless, empty, graceless, chromium world’), Patrick Hamilton (The Plains of Cement) and other writers of the period. They saw fear behind the Deco stained glass. In Dennis Potter’s 1930s-set masterpiece Pennies from Heaven, his doomed travelling-salesman hero Arthur Parker lives in just such a suburb, and oscillates between a joyous fantasy life and an actual life of frustration and anguish. Metro-Land is a perennially vanishing landscape of promise. Close the windows and draw the curtains, a storm is coming.

… for The London Column.

* You can read Andrew Martin‘s hymn of praise to the Tube here – and buy his wonderful history of same here.

See also: Pepys Estate, Nights at the Opera, St Pancras, Jubilee, Dmitri Kasterine, Underground, Overground, London Gothic, Trainspotters, Halloween, The Haunted House, A Haunted Bus.