Swansong.

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones 6 Comments Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

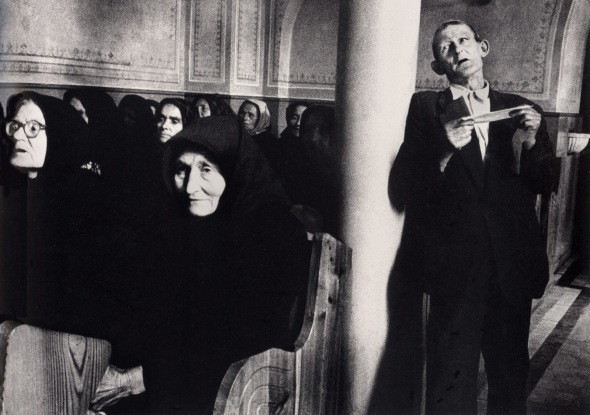

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

Dmitri Kasterine’s portraits.

Posted: November 26, 2013 Filed under: Artistic London, Bohemian London | Tags: Anthony Powell, David Niven, Dirk Bogarde, Dmitri Kasterine, Francis Bacon, Germaine Greer, Kingsley Amis, Martin Amis, Michael Caine, Paul Theroux, Roald Dahl Comments Off on Dmitri Kasterine’s portraits.

Martin & Kingsley Amis, London, 1975. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Martin & Kingsley Amis, London, 1975. © Dmitri Kasterine.

David Secombe:

There are too many photographers. Far, far too many. As the truism goes, these days everyone with a mobile phone is a photographer. Not only that, but everyone who’s been photographed is a celebrity. Current devalued concepts of achievement in the public sphere mean that the ever-increasing number of portrait photographers are faced with a chronic shortage of real, vital personalities worth photographing. (Celebrity chefs, boy bands, soap stars and their ilk – really?)

Dirk Bogarde, London, 1981. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Dirk Bogarde, London, 1981. © Dmitri Kasterine.

David Niven, Hertfordshire, 1979. © Dmitri Kasterine.

David Niven, Hertfordshire, 1979. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Major cultural figures are in short supply. Perhaps more to the point, the ones we’ve got don’t occupy the same space that they might have done 30 or even 20 years ago. Artists, writers, and thinkers used to be listened to as public figures; we’ve got no time for that now. For an ambitious portrait photographer, there are forums for the dissemination of photographic portraits as art, but such well-meaning, prize-giving endeavours seem culturally marginal and a more than little academic, when you compare them to the oracular power of a photograph that everyone was going to be looking at, of a person everyone was listening to.

Roald Dahl, Great Missenden, Bucks., 1976. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Roald Dahl, Great Missenden, Bucks., 1976. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Enter: a portfolio of limpidly beautiful portraits by Dmitri Kasterine, derived from his career as an editorial photographer in London and New York from 1960 to the 1990s. Looking at these pictures now, it is hard not to think, a little bitterly, that Dmitri was fortunate to be working before the internet, the population explosion, and a thousand TV channels splintered our attention forever; but it is also clear that he has the rare ability – it is genuinely rare – to photograph any human being with sovereign insight. His portrayal of everyday English life may be seen in this series of posts we ran in 2011; today, we are showing a selection from his chronicle of London’s intellectual life during the 70s-90s.

Germaine Greer London, 1975. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Germaine Greer London, 1975. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Part of Dmitri’s shtick (it almost looks like a shtick, these days) is an unassuming method: unobtrusive lighting, plain backgrounds, tones in the middle register … With simple means and an instinct for the essential, he penetrates his subjects’ defences far beyond the remit of a magazine portrait. Take the portraits of the actors on this page. There is genuine pain in his study of David Niven; Dirk Bogarde was reportedly unhappy with Kasterine’s portrait, its piercing honesty too much for the old matinee idol; and Michael Caine, denied his usual opportunity for Bermondsey charm or gangster menace, is revealed as a shrewd tycoon in ‘70s eyewear. Roald Dahl poses jauntily enough in summer gear, but his reptilian stare flatly contradicts his clothes’ carefree attitude, and forbids the viewer to find anything amusing. Paul Theroux, on the other hand, appears as if playing the part of a novelist: dominated by his accessories, he seems uncomfortable with the costume that wardrobe has assigned him.

Michael Caine, London, 1973. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Paul Theroux, London, 1974. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Paul Theroux, London, 1974. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Dmitri’s portrait of Kingsley and Martin Amis is a forensic document of English letters’ most awkward dynastic double act – Kingsley in his proto-Thatcherite pomp, the broken arm a possible souvenir of a drunken bender, and Martin exhausted by the sheer effort of trying to write better novels than his father. Anthony Powell determinedly maintains his aristocratic poise in the face of encroaching age, but the price is a whiff of camp – by contrast, Francis Bacon defiantly shows us the youthful hustler he once was.

Anthony Powell, Somerset, 1984. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Anthony Powell, Somerset, 1984. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Francis Bacon, London, 1978. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Francis Bacon, London, 1978. © Dmitri Kasterine.

Dmitri moved to America in 1985 and continued his career in New York: his Stateside subjects range from Saul Bellow to Cindy Sherman, Johnny Cash to Jean-Paul Basquiat, Steve Martin to Mick Jagger. Like Irving Penn, he captures his sitters by stealth. Now 80, he lives in Newburgh, New York, where he has been photographing the city and its inhabitants since 1992.

So many photographers are called to the profession with the burning desire to document the world, and that’s a noble thing. The gift is actually to be able to see it.

… for The London Column.

Calling at the Albany to see Graham Greene.

Posted: May 21, 2013 Filed under: Fictional London, Literary London | Tags: Albany, Dmitri Kasterine, Graham Greene, The Comedians 1 CommentGraham Greene, Antibes. © Dmitri Kasterine 1983.

Expedition to Greeneland by Susan Grindley

There was a problem with the spellings

of Yeastrol, or Yeastrel, and Tontons Macoutes.

I was the office junior, despatched

with marked-up galley proofs to Albany.

I washed and ironed my hair the night before,

wore my shift dress from Peter Robinson’s

new Top Shop with white stockings and white

patent shoes from Elliott’s of Bond Street.

I’d cracked the secret code to all his books –

women who thought that they were loved were not.

He kept them parked and waiting in the margins,

all that religious stuff – just an excuse.

I didn’t see him. I just left the envelope

with the top-hatted porter at the lodge.

I told them casually back at Production,

‘GG is lunching at his club today.’

© Susan Grindley. The poem is from Susan’s collection New Reader, published by Rack Press; also available from Waterstones, and The London Review Bookshop, 14 Bury Place, London, WC1A.

Dmitri Kasterine. Text: Tim Wells. (3/5)

Posted: October 26, 2011 Filed under: London Types, Sartorial, Shops | Tags: Bespoke tailoring, Dmitri Kasterine, Tim Wells Comments Off on Dmitri Kasterine. Text: Tim Wells. (3/5)Tailor, Putney. Photo © Dmitri Kasterine.

Dead Man’s Pockets by Tim Wells:

Things found in the pockets of Tim Wells, Saturday Night, 28.02.09

Right coat pocket – mobile phone (Liquidator as ringtone), spectacles.

Ticket pocket – a dozen of his own business cards, business cards for Niall O’Sullivan, Alice Gee and S. Reiss Menswear, return train ticket to Epsom.

Left coat pocket – keys – England fob, poem entitled ‘Self-Portrait as a P G Tips Chimp’, flyer for 14 Hour 14th march show with Karen Hayley, Ashna Sarkar, Amy Blakemore and others.

Inside coat pocket – an Elvis pen.

Right trouser pocket – £8.56 in assorted change.

Left trouser pocket – empty

Hip pocket – Oyster card and wallet

Wallet (black leather) – £160 in twenty pound notes, dry cleaning ticket, Leyton Orient FC membership card from 87/88 season, visa and cash card, picture of Joan Collins in window nook, horoscope stating ‘The first thing you have to ask yourself is what has to go; the second is what is going to take its place; and the third is where will I go to celebrate. Day done.’

© Tim Wells 2009.