Before the Blue Wall. Photos: Homer Sykes, text: David Secombe. (1/4)

Posted: July 10, 2012 Filed under: Vanishings | Tags: 2012 Olympics, Before the Blue Wall, Homer Sykes 1 Comment2012 Olympic site perimeter fence, Lea Valley. © Homer Sykes 2007.

David Secombe:

This week we are featuring a few of Homer Sykes’s images of the Lea Valley immediately prior to its transformation into the 2012 Olympic ‘zone’.

In 2006, searching to record for posterity a neglected moment in time, Homer made it his personal mission to explore the future site of the Olympic Park – soon to be encircled by a barrage of hype, and by the anonymous and blandly forbidding Blue Wall. Indeed, the blue wall shown in the picture above was the most visible token of the impending funfair – and it served as an unwittingly potent symbol of loss. In these images, Homer shows what was there before: a curious mix of wildflower meadows alongside neglected sports fields, semi-derelict 19th century industrial buildings sprawling cheek by jowl with unidentifiable dwellings cloaked in ivy – an almost rural atmosphere emanating, against all odds, from the urban blight.

Cities are organic entities, and London has, traditionally, ebbed and flowed as entire districts go in and out of fashion, or are repurposed in the light of changing circumstances. Elsewhere on The London Column, we have railed against the imposition of corporately-sponsored ‘Regeneration’ schemes upon areas that have developed their own post-industrial ecosystems: those intriguing backwaters where town becomes wilderness. Sadly, these romantic urban oases are too easily seen tabula rasa for this or that grand scheme – which are invariably sold in as a boon to the local community. But one only has to look at the dislocated, dystopian landscape of ‘North Greenwich’ to see what happens to an event site after the event has gone.

Homer will be presenting a slideshow of images from Before the Blue Wall at the Green Lens Gallery, 4a Atterbury Road, London N4 1SF, on Wednesday 11 July between 6 and 9 pm. Homer’s website is here.

London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (4/5)

Posted: July 5, 2012 Filed under: Pubs, The Thames, Vanishings | Tags: Dickens, J.G. Ballard, joggers of Wapping, our mutual friend, Town of Ramsgate, Wapping High Street, Wapping Old Stairs Comments Off on London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (4/5)Town of Ramsgate pub, Wapping Old Stairs. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

From Unknown London, W.G. Bell, 1919:

Wapping High Street in the days of Nelson’s wars possessed upwards of one hundred and forty ale-houses. In a recent perambulation I was not able to count ten. Together with these reeking drink shops, inexpressible in their squalor and dirt, were other houses of resort which one may deftly pass by without too curious enquiry. In the gloomy slum area at the back, the inner recesses of the hive, mostly dwelt the people who lived, quite literally upon the sailor, and they formed the greater part of the population that was herded here. Every tavern kept open door to welcome the mariner with wages in his pocket.

You may land at the Old Stairs still … The ‘Town of Ramsgate’ stands at the head of the Stairs, where it has stood these past two centuries or more for the refreshment of sailors. Wapping was the busiest centre of the seafaring life of the port of London. Of the many landing-places, the deserted Old Stairs and the New Stairs, nearer the City, alone survive. And you may tramp Wapping from end to end without recognizing a sailor man.

David Secombe:

Nearly a hundred years later, Bell’s assessment of Wapping remains valid, although these days the eeriness of its riverside enclave has a particularly 21st Century quality. Wapping High Street’s narrow pavements teem with joggers: driven young (or young-ish) men and women who appear from nowhere, pounding behind you silently before speeding past towards … what? Apart from the joggers, you may see a few tourists who make the journey to visit the pubs and riverside sights, and it is undeniably true that at certain times (dusk in November, for example) the environs of Wapping Old Stairs retain an impressive atmosphere: catnip for Dickens-fanciers armed with much-thumbed copies of Our Mutual Friend. However, in cold, hard daylight, the perfectly made-over warehouses and tastefully integrated new-build developments dispel memories of Dickens and recall instead the preoccupations of a more modern London writer: J.G. Ballard. Modern Wapping could be a starting point for one of his forensic studies of fear within insular communities, wherein the hot-house social conditions unleash perversity and violence behind the security gates of the ‘executive development’. In the 1970s, he set such a dystopia downriver, in a tower block that might have been designed by Erno Goldfinger (High Rise); but the make-over of ‘heritage’ environments, the loading-bays transformed into penthouses, offers a more contemporary setting for a Ballardian nightmare.

Ultimately, perhaps, the unnerving quality riverside Wapping possesses today is that of a ghost seen walking in the noonday sun: the ghost of London.

… for The London Column.

London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (1/5)

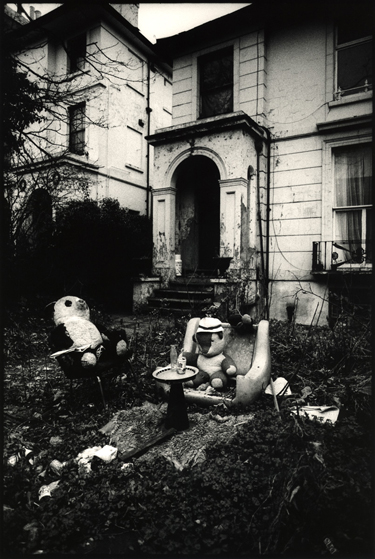

Posted: July 2, 2012 Filed under: Dereliction, Literary London, Vanishings, Wildlife | Tags: Arthur Machen, Camden, Holloway, London Gothic, Peter Ackroyd, tea party Comments Off on London Gothic. Photo & text: David Secombe. (1/5)Camden Road. © David Secombe 1987.

From London The Biography by Peter Ackroyd, 2000:

Whole areas can in their turn seem woeful or haunted. Arthur Machen had a strange fascination with the streets north of Gray’s Inn Road – Frederick Street, Percy Street, Lloyd Baker Square – and those in which Camden Town melts into Holloway. They are not grand or imposing; nor are they squalid or desolate. Instead they seem to contain the grey soul of London, that slightly smoky and dingy quality which has hovered over the city for many hundreds of years. He observed ‘those worn and hallowed doorsteps’, even more worn and hallowed now, and ‘I see them signed with tears and desires, agony and lamentations’. London has always been the abode of strange and solitary people who close their doors upon their own secrets in the middle of the populous city; it has always been the home of ‘lodgings’, where the shabby and the transient can find a small room with a stained table and a narrow bed.

David Secombe:

In the midst of our jingoistic Olympic summer, I thought it might refreshing to explore the aspect of London so eloquently evoked by Peter Ackroyd in the passage above. A city of silent yet inhabited houses, anonymous windswept streets, overgrown front lawns, strange objects on the back seats of abandoned cars, forbidding municipal playgrounds, etc. (This is essentially the same territory explored by Geoffrey Fletcher in The London Nobody Knows, and as the last series on The London Column was a revisiting of Fletcher’s book, this one may be seen as a continuation of the same theme.) ‘London Gothic’ is becoming increasingly rare; most of the streets that Arthur Machen thought of as woeful are now exemplars of prosperous gentrification. London is a cleaner, neater place: even King’s Cross is a landscaped zone now. The photo above was taken a quarter of a century ago, and Holloway has come up in the world since then. The specific, shabby London charm that Machen and Ackroyd describe may still be found, but one has to look harder. As a small boy visiting the city from the suburbs, I was amazed by the soft enveloping greyness which made the occasional bursts of colour all the more striking. That quiet visual texture is vanishing, when even municipal housing wears screaming day-glo colours, as 1960s & 70s blocks are clad in blue, yellow, or turquoise panels. London wears its dread in brighter shades these days.

… for The London Column.

The London Nobody Knows – revisited. Photos & text: David Secombe (3/4)

Posted: June 21, 2012 Filed under: Crime and Punishment, Vanishings | Tags: Geoffrey Fletcher, Peter the Painter, Sidney Street siege, The London Nobody Knows Comments Off on The London Nobody Knows – revisited. Photos & text: David Secombe (3/4)Sidney Street, Whitechapel. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

From The London Nobody Knows, Geoffrey Fletcher, 1962:

Half a century ago, the East End remained a closed book to the rest of London; hence the alarm created by the Hounsditch murders and the ensuing gun battle of Sidney Street. Londoners realized the unpleasant fact that there were gunmen in their midst and a vast floating population of refugees and anarchists living somewhere or other only a short distance from the opulent City. Peter the Painter, that elusive, unsatisfactory figure, and his gun-toting frienfds have always fascinated me, and I have visited the scene of their operations time and time and again. Whenever I go, in spite of modern changes (though there is a great deal left unchanged), I seem to see the top-hatted figure of Winston Churchill peering round a doorway during the gun battle, and policemen with walrus moustaches stare of the past, along with loungers in greasy cloth caps.

Sidney Street is more orderly today, and on the site of the siege the houses have been replaced by flats, but I remember the besieged house clearly … I also remember also a local coming out to watch me draw the house and telling me how he had watched the siege and the smoke coming out of the roof.

David Secombe:

Last year was the 100th anniversary of the Sidney Street Siege, and the full text of The Guardian‘s contemporary report may be read here. Peter the Painter, the legendary leader of the terrorists, was never found and uncertainty as to his real identity – indeed, doubts as to whether he ever actually existed – persist to this day. (In Julian Fellowes’s recent Titanic TV series, he had Peter the Painter on board the ill-fated liner, which prompted a few derisive guffaws round my neck of the woods.) In 2006, Tower Hamlets Council named a social housing complex on the corner of Sidney Street and Commercial Road after the mysterious renegade, a decision which brought complaints from the Metropolitan Police and others. The above photo was taken a few yards from the spot where 100 Sidney Street stood.

Fletcher’s account of the environs of Sidney Street was written fifty years after the siege, and The London Nobody Knows is all of fifty years away from us. Since Fletcher described the area with his antiquarian eye, the locale has developed newer sets of associations, newer urban mythologies. One strand of modern folklore which was brewing at the time of Fletcher’s early ’60s rambles eventually bore bloody fruit in a pub round the corner: a few steps from Sidney Street, on the Whitechapel Road, is The Blind Beggar, where Ronnie Kray shot George Cornell in 1966, and now a fixture on the unofficial London underworld coach tour. The Kray Twins were local, of course, and famously lauded as a positive force by a vocal assortment of cartoonish East End stereotypes. Local boys who made good and took care of their neighbours – a bit heavy handed sometimes, but they only fought their own. Violent but fair. That sort of thing. But that implausible golden era of neighbourly, family-loving criminals is as distant from us now as the Sidney Street Siege was to them, so it is no wonder that the 1960s East End seems impossibly exotic today. Back in the early ’90s, I spent an afternoon sightseeing in the East End with a former Kray associate, and we had lunch in Bloom’s, the famous kosher restaurant in Whitechapel High Street. As we entered the rather grand premises, my companion wistfully observed that ‘a few of the lads considered knocking this place over, back in the sixties. Lot of money used to come through here, all those nobs heading east for a bit of a thrill.’ Bloom’s finally closed in 1996, its heyday long past.

In the last three decades, Whitechapel has become predominantly Bangladeshi in its ethnic make-up, and the East London Mosque, opposite the Blind Beggar, is a kind of 20th century counterpart to Hawksmoor’s great Christ Church, Spitalfields. And, with a certain historical inevitability, present-day suspicions of the ‘immigrant’ community crystallise around their perceived terrorist potential – so in that respect, the East End of 2012 is remarkably similar to that of 1911.

… for The London Column.