On the natural history of gentrification.

Posted: October 7, 2014 Filed under: Class, Housing, London Types, Markets, Monumental, Public Art, Wildlife | Tags: animal art, Broadway Market, ha, Hackney Road rabbit, Hipster London, Irony and Boe, Poplar chihuahua, Roa, Southbank art Comments Off on On the natural history of gentrification. Chihuahua by Irony and Boe, Chrisp St., Poplar. © David Secombe 2014.

Chihuahua by Irony and Boe, Chrisp St., Poplar. © David Secombe 2014.

A London street artist writes:

I remember living in Hackney Wick around six years ago, just as it was being transformed from a barren industrial area into a ‘funky’ neighbourhood full of vegan coffee shops and ‘warehouse raves’ that had guest lists and cocktails, interspersed with re-purposed plant hire buildings that had been turned into artists’ studio spaces.

I had been a graffiti writer for about four or five years before moving there, and at that point in time I was spending a lot of time utilising the easy access to train tracks from Hackney Wick station to go painting at night. The thing was, Hackney Wick was full of ‘street artists’, yet I never saw any of them on my nightly overground rail missions. The reason for this was that they were mostly drinking chai tea in their studios, plastering canvases with stencilled pop-culture icons or images connoting cunning political/social commentary… But it was still ‘street art’. All the courtyards of the shared warehouse living spaces were covered in pieces, yet the streets surrounding them were bare.

Rabbit by ‘Roa’, Hackney Road. © David Secombe 2014.

Rabbit by ‘Roa’, Hackney Road. © David Secombe 2014.

This was the crest of the wave of socially acceptable, tongue-in-cheek street art. It was naughty, but only when it was allowed to be. It was rarely painted illegally, and rarely in places where lots of people could see it; inside the living room of a sandal-clad nut-loaf artisan, or on a peaceful stretch of canal. While the original breed of London graffiti writers tried to paint busy train lines and rooftops, these ‘street artists’ prefer to hit up Tumblr, Flickr and Twitter with photos of their work. ‘Getting up’ has been integral to graffiti culture since the beginning – it is the pure manifestation of the territorial roots of the art form, except now the art form is becoming gentrified, intellectualised and critiqued by Guardian columnists, and ‘getting up’ has turned into social media marketing. While all this is happening, grass-roots graffiti writers are still being locked up with criminal damage charges, sitting in police cells around the corner from a perspex-enclosed stencil that may or may not have been painted by Banksy.

Bird by Irony and Boe, Broadway Market, Hackney. © David Secombe 2014.

Bird by Irony and Boe, Broadway Market, Hackney. © David Secombe 2014.

Two street artists, Boe and Irony, recently painted a four story chihuahua on the side of a tower block. They suggest in an interview to have pulled this off without alerting anyone as to their activity. I mean, granted, the piece is nice. It’s a definite improvement over the old, plain brick wall, However, as someone who has spent their fair share of time crawling around on rooftops and side streets with buckets of paint, I don’t buy it. All credit to them if they actually managed to walk around the streets with their faces covered from the cameras, holding a fuck off ladder and the 20+ cans of spray paint they would have needed, set up shop on a residential building for 4+ hours and paint an entire face of said building without anyone even knowing they were there. That would be fucking impressive. There are writers who have been painting in this city for decades, who know all the dark secrets of how to get into train yards undetected and have hit up at least one rooftop in every borough in the city, who wouldn’t attempt a stunt like that.

Southbank Centre. © David Secombe 2014.

Southbank Centre. © David Secombe 2014.

Street art has always had its own lines of communication. Taggers, know each other by tag and reputation and possibly on the tracks. It’s territorial. Now, the territory is worldwide. The territory is in the bank. The artists get cash, the local authorities who pay them get kudos, and global gentrification accelerates week by week. ‘Street art’ is becoming just another kind of civic prettification – even the Southbank Centre has commissioned some to make itself appear more relevant. Individual neighbourhoods may get brightened up, but the work is mainly for the portfolio and the commercial opportunity.

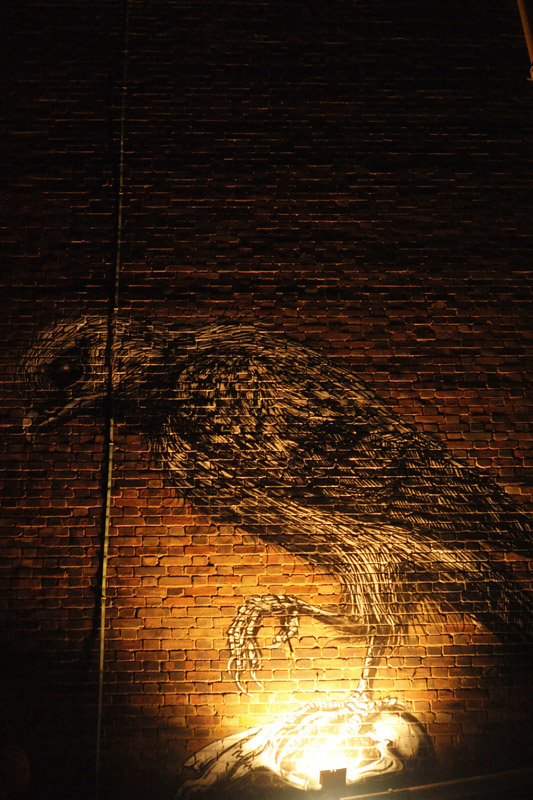

Bird of prey by ‘Roa’, off Rye Lane, Peckham. © David Secombe 2014.

Bird of prey by ‘Roa’, off Rye Lane, Peckham. © David Secombe 2014.

The big street animals are unobjectionable. Even the Daily Mail likes them. People didn’t want Hackney Council to paint over the rabbit in Hackney Road a few years back – it’s inoffensive and it got a reprieve (and no-one likes Hackney Council). But now you get big animals wherever business is moving in on an ‘up and coming’ area. I see a giant bird or squirrel or fox and all I see is money.

… for The London Column.

See also: Sugary Fun, On the South Bank, A Clockwork London, Sweet Toof.

Ten Old Men.

Posted: May 27, 2014 Filed under: Eating places, London Types, Pavements, Shops, Street Portraits, Transport | Tags: bowls, David Secombe, Kings Cross, old geezers, outdoor chess, Tim Marshall, Victoria Way, Woolwich Comments Off on Ten Old Men. Woolwich. © David Secombe 1998.

Woolwich. © David Secombe 1998.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

Finsbury Circus. © David Secombe 1998.

Finsbury Circus. © David Secombe 1998.

Clapham Common. © David Secombe 1998.

Clapham Common. © David Secombe 1998.

Spitalfields Market. © David Secombe 1990.

Spitalfields Market. © David Secombe 1990.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

King’s Cross. © Tim Marshall 2013.

Charlton. © David Secombe 1997.

Charlton. © David Secombe 1997.

See also: 38 Special, King’s Cross Stories, Underground, Overground, Deep South London, Spitalfields Market, Park Life, Ten Imperatives.

Recessional.

Posted: March 10, 2014 Filed under: Catastrophes, Class, Conspiracies, Corridors of Power, Housing, London scandals, London Types | Tags: banking crisis, CB Editions, filthy rich, housing crisis, Jack Robinson, Mayfair squatters Comments Off on Recessional.Jack Robinson:

This is my father driving in the 1940s, before I was born.

He left school at fourteen to work in an iron foundry his own father had helped establish; he eventually became joint managing director. We had a comfortable life without my mother having to work; single-income households were common then. He liked cars: I remember waiting at the front-room window one afternoon, when I was four or five years old, to see him arrive home in a brand-new olive-green Riley. Fifty years on from pressing my face against that window, I know that at no time has my own income been sufficient to raise a family in similar comfort, nor will I ever own a brand-new car; and my children will, if they go to college, be already mired in debt before they even begin to earn their own money.

The ignorance of the experts concerning the financial products they were using our money to buy is hardly new. James Buchan, in the late 1980s: ‘In London and New York I met people who invested fortunes in financial enterprises they simply could not describe or explain. No doubt quite soon, a bank would discover it had lost its capital in those obscure speculations; other banks would fail in sympathy . . .’ The politicians were even more ignorant. It’s as if for years we’ve been going with our tummy-aches to doctors who can’t tell the difference between a blister and a cancerous tumour. No wonder we’re ill.

The derivatives market conjured into existence in the 1990s was a virtual world, enabling speculation not in real assets but in the risk of speculation itself. It is addictive: the rush, the buzz, the winning streak. The opposite of which is the losing nose-dive – lose your job and you’re well on your way to losing your (real) house, marriage, health and dog.

An investment banker, quoted in the Standard: ‘In most cases they know their wives despise them for enslaving their lives to money, and they know that the moment they lose their job their wives will walk and take the kids, and their £3 million home, and divorce them.’ A lonely-hearts ad, placed on a literary website at the time the axe started to chop: ‘Ex-banker, 33 . . . Seeking woman not interested in money, fast cars, champagne, holidays, fleecing innocent hard-working gullible twats, whilst telling them you love them. Bitch.’

The above house in Mayfair, London, was squatted in January 2009 by a group that offered free workshops on welding, yurt-building, bookbinding, song-writing and de-schooling society. Hundreds of buildings are squatted; what made the press interested in this one was the stark disparity between the poshness of the building (alleged to be worth £22.5 million) and the presumed poverty of the squatters.

Bookbinding and yurt-building won’t change the world for the better overnight, but nor will sending out 400,000 repossession orders (Centre for Policy Studies estimate, February 2009) to households that have lost jobs and can’t keep up the mortgage payments.

I had a dream in which I punched the keys to withdraw money from a cash machine and it paid out in cowrie shells, rattling down a metal chute into the canvas bag I’d thoughtfully brought with me. As I walked to the supermarket the shells clacked satisfyingly in the bag by my side – I felt rich, rich. And then I woke up and went to my real bank and there was nothing there for me at all, they’d completely run out of money. Not a bean.

Ou sont les magasins d’antan? As well as the big ones, the small ones too. The place at the end of the road where I used to get my shoes re-heeled – where did that go? The café with over-priced food but a garden at the back where I could smoke? The minicab office in the next street? With the deadpan Somali driver who’d stop the car and get out and look up at the sky: he said he navigated by the stars, and I never knew whether he was taking the piss. Even with no office to return to, I hope that somewhere he’s still driving. There are very few recession-proof businesses; here is one of them.

The intensive factory farming of money makes it prone to many diseases, some of which can be transmitted to humans. There are government regulations concerning the application of biotechnology to the breeding of money, and there are also ways around them.In the last fifty years that part of the human brain dedicated to devising ways of getting money away from others and into your own hands has increased in size by 4 per cent.

He fell down the stairs. He slipped on the ice. He was coming home from work on Friday night when he got mugged – they took his money, his cards, his identity papers. They flung back his wallet, empty except for the photo of his kids – his kids to whom he’ll say, on Saturday morning, that he fell down the stairs, that he slipped on the ice

Behind this door – which is in a yard in the City of London – is the secret meeting place of a group of underground bankers. (There’s no external handle; you have to whisper the password through the grille on the right.) This group is deeply suspect: they buy books and music, not yachts and ski chalets, and their vocabulary extends beyond that of company reports. They are regarded by the rest of the banking world as heretics – because the whole point of being a banker is to speak in clichés, to have a single-track mind, to buy only the most predictable goods: that way they remain anonymous, almost invisible, and are left alone to get on with their thing.

God is dead (so can’t bail us out). Or couldn’t afford the heating bills for a place this big, or had had it up to here with the regular early-hours racket outside the lap-dancing club at the end of the street. Whatever the reason, he’s gone. But he left no forwarding address, so the mail just keeps piling up inside the door.

A selection from Recessional by Jack Robinson, published by CB Editions. © Jack Robinson 2009.