Swansong.

Posted: May 1, 2019 Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones 6 Comments Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

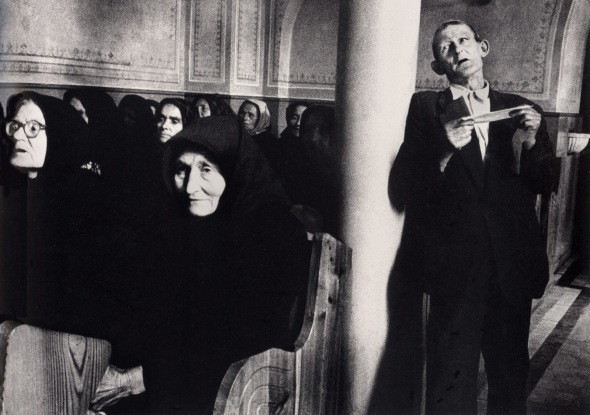

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

The Empty Office (for Peter Marlow).

Posted: March 11, 2016 Filed under: Interiors, Transport, Vanishings | Tags: Katy Evans-Bush, Peter Marlow Comments Off on The Empty Office (for Peter Marlow).

Empty Office, Clerkenwell, 2002. Photo © Peter Marlow.

Katy Evans-Bush:

The office as its redundant workers move out is spotted with relics of human degradation: that is, of the letdown from future perfect to mere life.

The screw stuck in the wall, reminder of that award for the old campaign that no one still here now remembers – although it was great work and targets were exceeded – surrounded by nails that hold their heads proud, knowing they held up the proofs of its successes.

Comfortable tea stains, paper clips wedged where the desk didn’t quite meet the wall, a blotched photo of Sarah who worked here half a decade ago, with a small child; she’d be wanting that back, if anyone knew where to find her now. Bits of phone chargers. A chocolate egg in foil. A bit of silk ribbon, some one-legged scissors, a dusty old bottle of Bristol Cream: why is it blue? Are they really that colour? A sad pile of paperbacks no one will ever read: Windows for Dummies and guides to blogging for businesses. Blu-Tack smears where no one thought they’d matter. Sticker-marks on the phones, where someone put the new supplier’s number. Dirt on the sills from the plants the receptionist had to water, because optimism always wins out. Optimism and sheer daily labour.

Things can’t stay clean forever. People are people and every negotiation will be tarnished. Its spreading spots will eat at your blind belief in silver and grey and the functional streamline that bypasses doubt and loops back to the bank, via mobile phones, and suits with reinforced shoulders, and platinum cardholders.

Forget your cheap tiles screaming masculine thrust from the Carpetland down on the roundabout. This office was made for pink fluffy sweaters, cake crumbs, to-do lists, pictures of cats, the darkening water in a vase, nail files and overstuffed folders.

… this is a reprise of one of The London Column’s early posts, from June 2011, in tribute to the English photographer Peter Marlow who died last month.

See also: Point of Interest (2), Point of Interest (3).