Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Owen Hatherley (2/3)

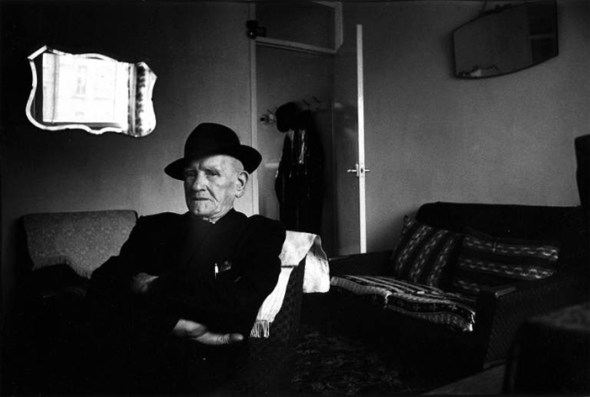

Posted: May 18, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Interiors | Tags: Owen Hatherley, Pepys Estate, RIBA, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Owen Hatherley (2/3)Elderly resident, Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo Tony Ray-Jones © RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Owen Hatherley writes:

Like a lot of council estates that have been subjected to the ministrations of ‘regeneration’, there are certain myths about the Pepys Estate. Each has a grain of truth, each covers up what ought to be a larger, more overwhelming truth.

My own experience of the place is fairly limited. I recall walking there from a flat in the centre of Deptford to hand in my form for the council waiting list; on a few other occasions I would wander over to use the bridge that connected the estate to Deptford Park, just for the fun of it, for the fact of its mere existence. The place seemed quiet during the day; I only saw it at night as the N1 bus looped around it. So I can’t offer much insight into what it was ever like to live there, but I have watched the material transformations of the place over the last decade or so, and watched the media discourse around it spin its web.

The Pepys is often presented as a monolithic, monstrous estate that was a failure from day one. Which is interesting, as the place marked one of the earliest council schemes to preserve as well as demolish – the little enclaves of Georgian nauticalia that mark the estate’s edges were part of the scheme, renovated and let by the council as an integral element, by now surely long since lost to Right to Buy. The rest of it is, or rather was, a series of jagged, mid-rise blocks connected by walkways, enclosing three towers and a large open space, with the bridges eventually leading to a park on the other side of Evelyn Street. In the middle is a community building with a bizarre, expressionist roofline seemingly partly based on oast houses (but then, so is Bluewater).

What is undoubtedly true is that parts of it were badly made – the lifts were apparently prone to breakdown from extremely early on. The draughty blocks were clad in plasticky white material at some point in the 1980s. Yet what happened when the place got ‘regenerated’ is by far the most dramatic aspect. The open space went, with low-rise flats to be sold to ‘key workers’ and on the open market taking an already highly dense area and making it more so. This accordingly makes it more ‘mixed’, ‘vibrant’ and ‘urban’, as professionals now live alongside – well, not quite alongside, but at least near to, council tenants.

The bridge over Evelyn Street went also, with remarkably clumsy ‘eco-flats’ (you can tell this, because the extra layer of curved glass on the façades a few feet from the actual windows could surely have no other possible functional justification) built where it met the park. This ‘recreated a street pattern’ in the area according to planning ideologists; or it defaced an area of public space. As you wish.

The new blocks are regeneration hence good, the old are council housing hence bad. Yet the council flats are much larger, and look much more robustly built, of concrete and stock brick – the newer flats are clad in the ubiquitous thin layer of brick or attached slatted wood, materials which have shown an unfortunate tendency to fall off. The major story is with one of the three towers – the one nearest to the river, naturally – which was completely cleansed of undesirables and sold instead as Z Apartments, luxury riverside living. It became a brief cause celebre via class war reality TV show The Tower.

All this, in theory, funds the regeneration, meaning in this case the cleaning and patching up, of the older buildings, or alternatively to their phased, currently seemingly stalled, demolition. None of the new buildings in the Pepys Estate – or anywhere else in London – have been council housing, though its regeneration has entailed several once council flats going private. The waiting list, nationally, is reckoned to be five million.

… for The London Column. © Owen Hatherley 2011.

Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman. (1/3)

Posted: May 17, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Literary London, London on film, London Places | Tags: Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman, Pepys Estate, Tony Ray Jones Comments Off on Pepys Estate, Deptford. Photo Tony Ray-Jones, text Edward Mirzoeff, John Betjeman. (1/3)Pepys Estate, Deptford, 1970. Photo © Tony Ray-Jones/RIBA Library Photographs Collection.

Edward Mirzoeff writes:

Bird’s-Eye View was a pioneering series of 13 films shot entirely from a helicopter. For the first of these, The Englishman’s Home (BBC2 5 April 1969) John Betjeman wrote in the commentary about the new high-rise blocks. At the time his strongly-felt views were very much against progressive liberal thinking on the subject, and what he wrote was attacked and derided. By now most people have come round to his old-fashioned but humane way of thinking.

Betjeman refused to fly in the helicopter, but wrote his commentary, in verse, over weeks in the cutting room, once the picture-editing had been completed.

[Edward Mirzoeff was the producer of Bird’s Eye View.]

Pepys Estate, Deptford by John Betjeman:

Where can be the heart that sends a family to the 20th floor

In such a slab as this.

It can’t be right, however fine the view

Over to Greenwich, and the Isle of Dogs.

It can’t be right, caged halfway up the sky

Not knowing your neighbour, frightened of the lift,

And who’ll be in it, and who’s down below

And are the children safe?

What is housing if it’s not a home?”

[Tony Ray-Jones was one of Britain’s finest photographers, whose early death – at just 30 – in 1972 robbed us of an artist of acute insight and integrity. His book A Day Off is celebrated as one of the definitive post-war photographic studies of British life, and influenced a generation of native photographers, not least Martin Parr whose early work showed an obvious debt to Ray-Jones. Until I went searching for means of contacting the Ray-Jones estate, I was unaware of his work for Architectural Review in 1970: a total of 138 pictures that are now in the RIBA photographic library. These are images of the impact of modern housing, and he responded to the brief with characteristic power; he seems to have been especially engaged with the London subjects – Deptford, Thamesmead, the Old Kent Road, etc. – and some of these pictures are the equal of his better-known work. The London Column will be running a further two images from TRJ’s series on the Pepys Estate later this week. Special thanks to Robert Elwall at RIBA Library Photographs for allowing us to reproduce them here. D.S.]

Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe (5/5).

Posted: May 13, 2011 Filed under: Architectural, Transport | Tags: blackwall tunnel, Greenwich Peninsula, Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, Owen Hatherley Comments Off on Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe (5/5).The Dome seen from the Blackwall Tunnel southern approach. Photo © David Secombe 2004.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain*, Owen Hatherley 2010:

This place was a Blairite tabula rasa. Faced with an area the size of a small town, freshly decontaminated and waiting to have all manner of ideas laid down upon it, what did they create – or rather, what did the companies and corporations that they subsidized create? A couple of areas of luxury housing (typically, with fairly minisucule apartments) a couple of shopping centres, several car parks, and now a gigantic Entertainment Complex to finally get those car parks filled. Amusingly, given that the area was once so keen to trumpet its eco credentials (a supermarket partly run on wind power), it has since become another of London’s locked traffic grids, as well it might having the Blackwall Tunnel nearby. Blairites, and neoliberals in general, have always posited some sort of ‘force of Conservatism’, some entrenched opposition either from the remnants of organized Labour or woolly traditionalists, that prevents their vision from being realized. Here, there was nothing but blasted wasteland when they got hold of it. Yet a more astounding failure of vision is difficult to imagine. If there is a vision here, it’s of a transplant of America at its worst – gated communities, entertainment hangars and malls criss-crossed by carbon-spewing roads; a vision of a future alienated, blankly consumerist, class ridden and anomic. The ‘corrosive humours’ turned out to be more difficult to erase than might have been imagined.

* published by Verso. © Owen Hatherley 2011.

Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe. (4/5)

Posted: May 12, 2011 Filed under: Architectural | Tags: Ford Sierra, Greenwich Peninsula, Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain, Owen Hatherley, the O2 Comments Off on Domeland. Text Owen Hatherley, photos David Secombe. (4/5)Bugsby’s Way, SE10. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

In 2006, the Millennium Dome was bought by the magnate Philip Anschutz who planned to open ‘Britain’s first Supercasino’ and an entertainment complex within it, whilst the phone company O2 paid for it to be rebranded ’The O2’.

From A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain* by Owen Hatherley, 2010:

I attended Open House here in 2006, hoping to be able to see inside this fabulously enormous, hubristic space, able to fit several football pitches inside it, Canary Wharf laid flat, amongst other dubious statistical feats. The reality was rather more disappointing, as Anschutz employees showed nonplussed architecture buffs nothing but the small space where the Casino was being constructed – to no avail, as the Supercasino permission was given to New Emerging Manchester instead, until the plans for these gambling cathedrals were cancelled by Gordon Brown upon taking power. Nonetheless, the Dome was reopened in June 2006, its ceremonial opening a concert by bafflingly enduring hair metal act Bon Jovi.

Around the time the Dome was reopened as the O2, the renovated Royal Festival Hall had also just opened upriver to much fanfare. This fragment of the 1951 exhibition appears as the upscale, upriver entertainment centre, with the Dome as the prolefeed easterly equivalent. Inside, the newly reopened Dome resembles an Arizona shopping mall, only sheathed in greying Teflon. The whole area is ‘themed’ in a Grand Theft Auto art deco, and I wonder what Richard Rogers and Mike Davies think about what happened to their building. A ‘chill-out zone’ consists of a tent filled with iPods. Decorated guitars and fibreglass palm trees punctuate the ‘streets’, while outside a billboard proclaims a little history of entertainment – 1951 Frank Sinatra, 1983 ‘Metallica invents Speed Metal’, 1995 Blur vs Oasis – emblazoned on a series of gurning crowds.

* published by Verso. © Owen Hatherley 2010.