Pinteresque. Photo & text: David Secombe (2/3)

Posted: March 8, 2012 Filed under: Fictional London, London on film | Tags: Chelsea Drugstore, Dirk Bogarde, Harold Pinter, James Fox, Joseph Losey, Sarah Miles, The Servant Comments Off on Pinteresque. Photo & text: David Secombe (2/3)Royal Avenue, Chelsea; looking south from King’s Road. Photo © David Secombe 2010.

BARRETT: She’s living with a bookie in Wandsworth. Wandsworth!

– from Harold Pinter’s screenplay for Joseph Losey’s The Servant, 1963.

No. 30 Royal Avenue in Chelsea – on the right hand side in the above photo – was used for the location filming of Pinter and Losey’s class psychodrama The Servant (from a novel by Robin Maugham, who seems to have been written out of the picture completely). The plot has BARRETT (Dirk Bogarde) being engaged as a manservant by TONY (James Fox), an ineffectual toff who has just taken ownership of a house in Royal Avenue. BARRETT takes charge of the refurbishment of the house and, bit by bit, the destruction of TONY, whose increasing reliance upon BARRETT reflects the weakness of his personality and the inherent decadence of his class. (Discuss.) The action culminates in a sort of fully-clothed orgy at which Bogarde, Fox, Sarah Miles and Wendy Craig engage in a Mexican stand-off whilst listening to Cleo Laine. This was regarded as ground-breaking cinema when it premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1963.

The script features some of Pinter’s best lines on film, and showcases Losey’s bravura directorial technique as well as his ambivalent approach to British society (Losey himself lived in Royal Avenue). It also features the glorious black and white cinematography of Douglas Slocombe, including location shooting around Chelsea, which, in and of itself, is a precious document of a lost age: the ‘black and white 60s’, the pre-Beatles 60s.

A few years later, The Chelsea Drugstore opened on the corner of King’s Road and Royal Avenue: an artefact of Swinging London proper, this establishment was used as a location for the filming of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange and was hymned by The Rolling Stones in You can’t always get what you want. By that time, James Fox had been bamboozled in a rather more emphatic fashion – the class element reversed – by Mick Jagger and Anita Pallenberg in Roeg and Cammell’s Performance. This latter, filmed up the road in Notting Hill, was made a mere five years later, yet it makes the Chelsea of The Servant – folk singers (Davey Graham) in wine bars, Sanderson wallpapers, ski-pants, pork pie hats, sheepskin coats over cable-knit jumpers, class warfare over Dubonnet and soda – seem as distant as the Chelsea of Rossetti or Oscar Wilde.

The Servant at IMDB.

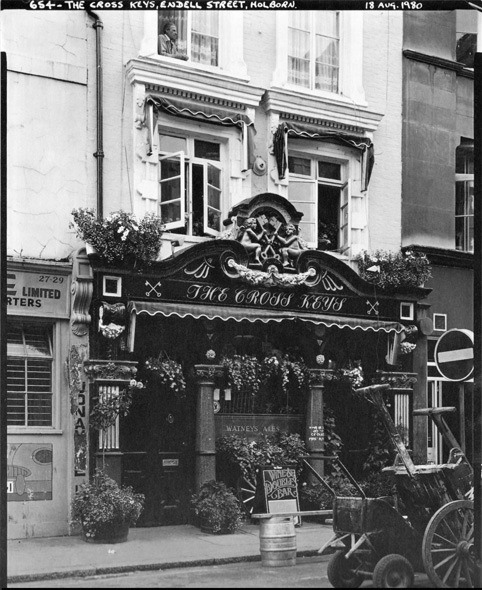

Drinker’s London. Photos Paul Barkshire, text David Secombe. (4/5)

Posted: October 22, 2011 Filed under: Eating places, Fictional London, Food, London on film, Pubs | Tags: El Vino's, Hugh Grant, Kate Winslet, Old Wine Shades, Richard Curtis Comments Off on Drinker’s London. Photos Paul Barkshire, text David Secombe. (4/5)Old Wine Shades, Martin Lane. Photo © Paul Barkshire, 1981.

Old Wine Shades is part of the El Vino group, the venerable drinking chain that branches across the City of London. The one on Fleet Street was a legendary haunt of the local hacks in the days when ‘the Street of Shame’ was thronged with them, and El Vino’s continues to trade on its reputation as a City institution. However, an anonymous reviewer (‘A Customer’) on www.allinlondon.co.uk recently (August 2010) described Old Wine Shades thus:

A dreadful place. I work close by and El Vino’s is noted for rude staff and overpriced food and (especially) drink. On one of my few unavoidable visits (guest of others), my dining partner found a lady’s bracelet at the bottom of his coffee cup. A significantly chunky piece of jewellery. Not even an apology offered, much less anything off the bill. Basically, they trade on their historical connections and for that it’s worth a visit, but only on the way to somewhere better.

I have no idea if this is a fair assessment overall, but it poses several questions: what kind of bracelet was it? Did it have precious stones? What was it doing at the bottom of a coffee cup? Had its owner thrown it there as a protest? (surely you’d notice if your bracelet slipped from your wrist and into your cappuccino). Perhaps it was a prop left over from the filming of a romantic comedy, and the scene is easy to picture: a lunch date goes wrong in an historic London location, Kristin Scott-Thomas chucks her bracelet – a gift from Hugh Grant – in his coffee, leaving him embarrassed as she stalks off. We’d then have a quick bit of comic business with the waiter, a star cameo from Ricky Gervais. Hugh would probably pay another visit to Old Wine Shades at the end of the film, this time blissfully entwined with Kate Winslet or Kate Beckinsale, etc., who then finds the bracelet at the bottom of her coffee cup. I am sure I’ve seen this film. D.S.

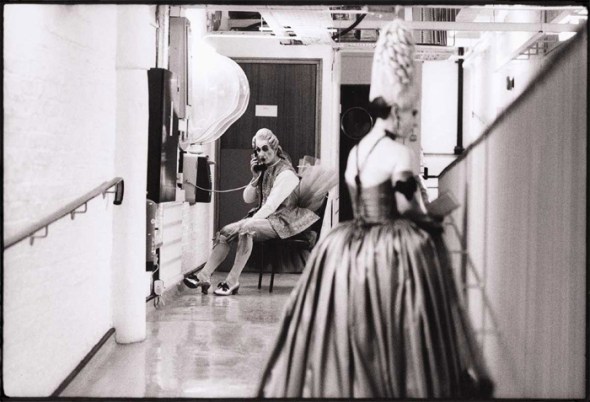

Nights at the Opera. Photo David Secombe, text Edward Mirzoeff (1/5)

Posted: August 1, 2011 Filed under: Interiors, London Music, London on film, Theatrical London | Tags: royal opera house, The House, wig Comments Off on Nights at the Opera. Photo David Secombe, text Edward Mirzoeff (1/5)Backstage, Royal Opera House. Photo © David Secombe 1994.

Edward Mirzoeff writes:

The House was, in many ways, the definitive “fly-on the wall” television documentary series. The six episodes, shot in 1993 and 1994, went behind the scenes at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden to reveal the astonishing dedication, talent and sheer hard work put in by singers, dancers, technicians and craftspeople in decaying and unhelpful surroundings. It also revealed the equally astonishing conflicts, confusions and ineptitudes of some members of the management and some grandees on the Boards.

The television audience, and newspapers all over the world, were gripped by the saga from week to week. Some people took it as an allegory of the state of the nation. And after it was over, the series went on to win all the prizes. BAFTA, Banff Festival, Broadcasting Press Guild, International Emmy, Royal Philharmonic Society – The House cleaned up all the statuettes.

Just one puzzle remained. Despite the many awards, despite the publicity and controversy, the series was never shown again. In a culture of endless repeats of mediocre television programmes, such restraint by BBC Controllers was curious.

[Edward Mirzoeff was executive producer of The House for BBC Television.]