Posted: May 1, 2019 | Author: thelondoncolumn | Filed under: London Music, London Types, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Andrew Martin, Angus Forbes, Charles Jennings, Christopher Reid, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, Don McCullin, Homer Sykes, John Londei, Katy Evans-Bush, Marketa Luskacova, old East End, Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O'Donaghue, Spitalfields, Tate Britain, Tim Marshall, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, Tony Ray Jones |

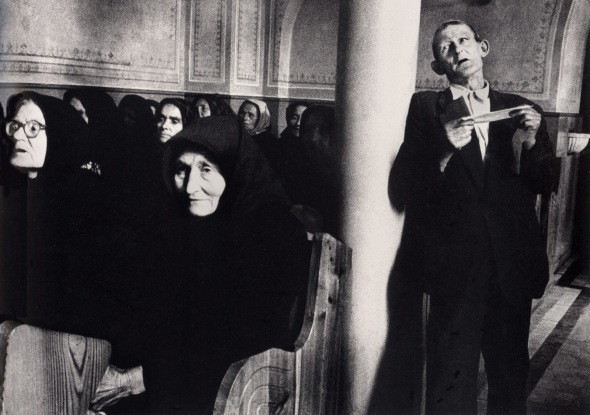

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

I have not found a better place than London to comment on the sheer impossibility of human existence. – Marketa Luskacova.

Anyone staggering out of the harrowing Don McCullin show currently entering its final week at Tate Britain might easily overlook another photographic retrospective currently on display in the same venue. This other exhibit is so under-advertised that even a Tate steward standing ten metres from its entrance was unaware of it.

I would urge anyone, whether they’ve put themselves through the McCullin or not, to make the effort to find this room, as it contains images of limpid insight and beauty. The show gathers career highlights from the work of the Czech photographer Marketa Luskacova, juxtaposing images of rural Eastern Europe in the late 1960s with work from the early 1970s onwards in Britain. There are overlaps with the McCullin show, notably the way that both photographers covered the street life of London’s East End in the early ‘70s. Their purely visual approaches to this territory are remarkably similar: both shoot on black and white and, apart from being magnificent photographers, both are master printers of their own work. The key difference between them is that Don McCullin’s portraits of Aldgate’s street people are of a piece with his coverage of war and suffering — another brief stop on his international itinerary of pain — whereas Marketa’s pictures are more like pages from a diary, which is essentially what they are.

Marketa went to the markets of Aldgate as a young mother, baby son in tow, Leica in handbag, to buy cheap vegetables whilst exploring the strange city she had made her home. This ongoing engagement with her territory gives Marketa’s pictures their warmth, which allows her subjects to retain their dignity. They knew and trusted her.

Marketa’s photos of the inhabitants of Aldgate hang directly opposite her pictures of middle-European pilgrims and the villagers of Sumiac, a remote Czech hill village — a place as distant from the East End as can be imagined. Seeing these sets alongside each other illustrates her gift for empathy, and some fundamental truths about the human condition.

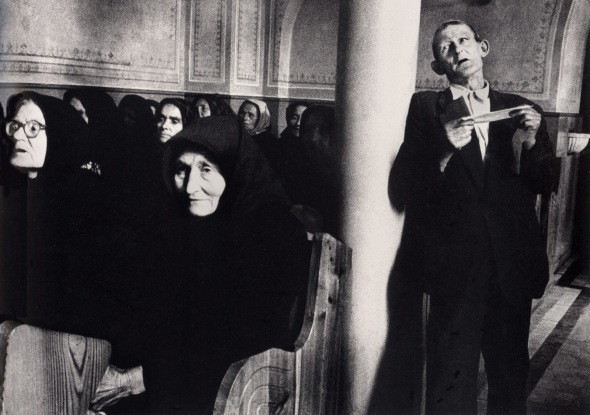

Two images on this page are of men singing: the second is of a man singing in church as part of a religious pilgrimage in Slovakia. This is what Marketa has to say about it:

During the pilgrimage season (which ran from early summer to the first week in October), Mr. Ferenc would walk from one pilgrimage to another all over Slovakia. He was definitely religious, but I thought that for him the main reason to be a pilgrim was to sing, as he was a good singer and clearly loved singing. During the Pilgrimage weekend the churches and shrines were open all night and the pilgrims would take turn in singing during the night. And only when the sun would come up at about 4 or 5 a.m., they would come out of the church and sleep for a while under the trees in the warmth of the first rays of the sun [see pic below]. I was usually too tired after hitch-hiking from Prague to the Slovakian mountains to be able to photograph at night, but in Obisovce, which was the last pilgrimage of that year, I stayed awake and the picture of Mr Ferenc was my reward.

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Marketa’s pictures are the kind of photographs that transcend the medium and assume the monumental power of art from the ancient world. As it happens, they are already relics from a lost world, as both central Europe and east London have changed beyond recognition. Spitalfields today is more like a sort of theme park, a hipster annexe safe for conspicuous consumers. In Marketa’s pictures we see London as it was, an echo of the city known by Dickens and Mayhew. And the faces in her pictures …

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

The photo at the top, of a man singing arias for loose change in Brick Lane, has featured on The London Column before. It is one of the greatest photographs of a performer that I know. We don’t know if this singer is any good, but that really doesn’t matter. He might be busking for a chance to eat – or perhaps, like Mr. Ferenc, he just loves singing – but his bravura puts him in the same league as Domingo or Carreras. As with her picture of Mr. Ferenc, Marketa gives him room and allows him his nobility.

As they say in showbiz, always finish with a song: this seems like a good point for me to hang up The London Column. I have enjoyed writing this blog, on and off, for the past eight years; but other commitments (including another project about London, currently in the works) have taken precedence over the past year or so, and it seems a bit presumptuous to name a blog after a city and then run it so infrequently. And, as might be inferred from my comments above, my own enthusiasm for London has suffered a few setbacks. My increasing dismay at what is being done to my home town has diminished my pleasure in exploring its purlieus (or what’s left of them).

It seems appropriate to close The London Column with Marketa’s magical, timeless images. I’ve been very happy to display and write about some of my favourite photographs, by photographers as diverse as Marketa, Angus Forbes, Dave Hendley, David Hoffman, Dmitri Kasterine, John Londei, Homer Sykes, Tim Marshall, Tony Ray Jones, etc.. It has been a great pleasure to work with writers like Andrew Martin, Charles Jennings, Katy Evans-Bush (who has helped immensely with this blog), Owen Hatherley, Owen Hopkins, Peadar O’Donaghue, Christopher Reid, Tim Turnbull, Tim Wells, and others. But now, as they also say in showbiz: ‘When you’re on, be on, and when you’re off, get off’.

So with that, thank you ladies and gents, you’ve been lovely.

David Secombe, 30 April 2019.

Marketa Luskacova’s photographs may be seen on the main floor of Tate Britain until 12 May.

Posted: December 22, 2014 | Author: thelondoncolumn | Filed under: Amusements | Tags: David Hoffman, London in the 1970s, old people's clubs, Tower Hamlets in the 1970s |

Christmas Party at an old peoples’ lunch club in Tower Hamlets, 1975. © David Hoffman.

Christmas Party at an old peoples’ lunch club in Tower Hamlets, 1975. © David Hoffman.

As Christmas draws near, The London Column’s seasonal offering is these two exquisite photographs by national treasure David Hoffman.

© David Hoffman 1975.

© David Hoffman 1975.

I would like to wish all our readers and contributors a very happy Christmas and a peaceful and prosperous new year. D.S.

Posted: November 18, 2014 | Author: thelondoncolumn | Filed under: Food, Health and welfare, London Music, London Types, Markets, Pavements, Performers, Vanishings | Tags: Brick Lane, David Hoffman, London street musicians, one man band, Tower Hamlets, Turkish baths Hackney |

Street market, Cheshire Street, Tower Hamlets 1981.

Street market, Cheshire Street, Tower Hamlets 1981.

As a counterweight to David Hoffman’s images of urban protest which we ran last week, here are a few of David’s pictures of a more peaceful London. Peaceful and largely vanished … these photographs have an elegiac quality to them, glimpses of a city that seems almost as remote as the one pictured by Thomson or A.L. Coburn. In any case, they require no further comment from me … D.S.

Turkish baths, Clapton, Hackney 1983. © David Hoffman.

Turkish baths, Clapton, Hackney 1983. © David Hoffman.

Street musician, Brick Lane, 1978. © David Hoffman.

Street musician, Brick Lane, 1978. © David Hoffman.

Silver Jubilee, Tower Hamlets, 1977. © David Hoffman.

Silver Jubilee, Tower Hamlets, 1977. © David Hoffman.

One Man Band, Brick Lane area, 1984. © David Hoffman.

One Man Band, Brick Lane area, 1984. © David Hoffman.

Tea time at an old peoples’ club in Tower Hamlets 1975. © David Hoffman.

Tea time at an old peoples’ club in Tower Hamlets 1975. © David Hoffman.

As part of East London Photomonth, David’s images are on display until the end of this month at a variety of cafes forming the ‘Roman Road Cafe Crawl’. David’s show at Muxima cafe runs until 27th of November. More details here.

Posted: November 11, 2014 | Author: thelondoncolumn | Filed under: Conspiracies, Crime and Punishment, London scandals | Tags: Brixton riots, David Hoffman, East London Photomonth, G20 protests, Poll Tax Kiss, Roman Road Cafe Crawl, social unrest in London, Stop the City, Swamp 81 |

Poll tax riot kiss © David Hoffman 1990.

Poll tax riot kiss © David Hoffman 1990.

David Hoffman:

I’ve been fascinated by photographs for as long as I can remember. The school darkroom was a welcome teacher-free refuge. In my teens my first published photo was of an arrest outside Parliament. I got paid three guineas! About £100 in today’s money, rather more than they’d pay today. But then I got distracted by truck and van driving and a bit of education until I started taking photographs in earnest in 1976.

I’ve only been photographing social change and protest for 38 years, but even in my time I’ve seen massive changes in the way that protest has been policed.

Youth faces police during the Brixton riots. © David Hoffman 1981.

Youth faces police during the Brixton riots. © David Hoffman 1981.

It seems to me that police lost their sense of direction in policing protest after the wave of anti-Thatcher riots that swept across the country in 1981. Rather than understanding and adapting to social change, the police responded by opposing it and trying to prevent it. Since then, attempts to control and contain protest have led to growing antagonism on both sides, and an escalation of conflict between activists & police.

This has created a vicious circle with suppression of protests leading to angrier, more determined protests. That in turn has been seized upon to legitimise a more military style of policing with shields, body armour and Tasers now standard items in the police kitbag.

The police have tremendous power to assist or to stifle protest. It is their actions that determine whether a protest is peaceful or violent. With that power comes an obligation to be open to scrutiny and to be visible and accountable. But what we have seen is very different. The police have formed multiple secret undercover units, they have stepped up surveillance on responsible citizens working for a better society, they have built a network of secret databases and have done all that they can to undermine movements for social change.

As the police have become more involved in shaping protest, so it becomes even more important that their actions and behaviour are openly reported.

G20 police officer, and protestor on ground. © David Hoffman 2009.

G20 police officer, and protestor on ground. © David Hoffman 2009.

I took this photograph as this protester was knocked to the ground by police and was, I believe, about to be punched by the officer shown. As my flash went off I saw the officer visibly restrain himself and in the event the man on the ground was not hit.

I’ve seen countless brutal and unjustifiable assaults on passive protesters, but my role at protests is as a photographer, documenting the events – not intervening directly. The more dispassionate I can be, the stronger and more useful I think my pictures become.

Photographers trying to record the process of social change are under pressure from both sides. Attacks on protesters are bad enough – but attacks on working journalists are attacks on democracy and on society’s ability to make informed decisions. Showing these processes in action is all too often seen by police as criticism and an attempt to constrain their activities. In response the police have targeted photographers, who have found themselves stopped, harassed, assaulted and surveilled, with their activities logged on secret databases by special units. At the same time protesters increasingly see photographers as ‘spies’ for the police or as reactionary propagandists working for an unloved and untrusted press.

Black arrest, hidden truncheon. © David Hoffman 1979.

Black arrest, hidden truncheon. © David Hoffman 1979.

In the ’70s ,aggressively racist policing in Notting Hill continued to raise the tensions that had been building there for decades. This, combined with discrimination in jobs and housing, turned hopeful young citizens into an angry subculture of black youth. This was then targeted by police, creating a feedback loop with young people reacting violently each year to the confrontational, high-profile policing at Carnival and the police in turn reacting by stepping up their own violence. So we have this kind of policing – look at the sleeve of the PC with his arm round the young man’s neck. There’s a truncheon up his sleeve, nobody sees as it rams into the kid’s jaw. It is hardly surprising when that leads to this:

Youths Attack PC. © David Hoffman 1979.

Youths Attack PC. © David Hoffman 1979.

I grabbed that photo as more police arrived and the attackers ran off. So the hyped-up police beat me to the ground and tried to grab my camera. That sort of set the tone for the next 30-odd years.

The 1981 Brixton riots started because of just this mistrust of police. It was brought to a head by the pressure of Swamp 81, a heavy-handed racist stop-and-search operation specifically targeting black people. The riots caught the police unprepared. It was the first time I’d seen police in retreat. They had almost no shields or protective clothing, just pointy hats and dustbin lids grabbed from the street. Fear and desperation led police to an ‘anything-goes’ attitude. The police behaviour was uncontrolled and outrageous. At night they went out hunting. I slipped through a cordon and was standing with a group of nervous police by an alley off Coldharbour Lane when I saw this group of police in civvies carrying homemade weapons – pickaxe handles, a heavy chain. They didn’t look like police. I heard one cop ask “who are these thugs?” and another replied “It’s OK, They’re our thugs.” I snapped off just one frame before I was firmly ‘advised’ to stop. A moment after this police group passed me, all the street lights in the alley went off, and they disappeared into the darkness. A moment later I heard screaming and thudding as these policemen laid into anyone they could find. Anyone. Young men and women staggered out bleeding. There was no attempt to arrest anybody, it was just an exercise in violently beating people off the streets.

Stop the City demonstration. © David Hoffman 1983.

Stop the City demonstration. © David Hoffman 1983.

A couple of years on, 1983, still 25 years before the banking crisis and the credit crunch but the anarchists of the ‘80s were well ahead of the game with the first Stop the City demo – a protest against globalisation, big business and the banks.

The police sergeant here is strangling a protester who had photographed him strangling another protester. Then he dropped this guy and thought he’d strangle me. It was just that sort of day. Behind that picture lies a revealing story about just how far some cops will go for no reason but the enjoyment of their power.

I’d been around from about 7 o’clock, sharp as a rubber razor and so bleary as to be near invisible. I was hanging around by the Bank of England when Kieran – he’s the one getting his neck squeezed – saw this sergeant doing his thing on the neck of yet another chap. So Kieran takes a photograph. The sergeant spots him. A moment later the sergeant has dropped the first guy and is moving in on photographer Kieran. The long fingers of the law wrap around his neck.

Of course I’d not noticed any of this. But I did notice a group of three cops making off with their prey in my direction. I continued to gaze vacantly into space until they reached me. I raised the camera and fired off three quick frames. Then I ran away, jumped a cab and got the film away double quick. Meanwhile the sergeant and his mates had dumped a half unconscious Kieran in the gutter and set off looking for me; but I was well away so, disappointed, the cops plod their way back to the gutter, re-nab the still dazed Kieran and off to the nick with him. Job well done. Well, not quite. Kieran was charged – assault on a policeman’s fingers with his throat or something. In court the sergeant said “I never touched him” and claimed that my photograph was a fake. The prosecution called in an expert from Scotland Yard who took just seconds to confirm that the image was genuine and unaltered. Keiran was acquitted. He sued the police, got £4,000 and formed a punk band.

Poll tax riot, mounted police, Trafalgar Square. © David Hoffman 1990.

Poll tax riot, mounted police, Trafalgar Square. © David Hoffman 1990.

1990 saw the Poll Tax protests, a series of demos which got more and more angry with Thatcher and with the aggressive policing. There were major protests in Brixton, Hackney, Islington, and finally Trafalgar Square. What I found interesting was how the police dealt with the angry crowd.

In every case the police had the crowd contained, and had the opportunity to disperse the protesters into open spaces nearby. Instead, they chased them violently towards high-value shopping areas. This time I had no trouble from police. There seemed to be a deliberate plan to ensure that there would be photos of looting & smashed shops for the next day’s papers. That can only have been a high-level decision intended to move debate away from the Poll Tax and to discredit the protest. Once or twice might possibly have been explained as poor decision-making, but with military precision this happened at every one of those five protests.

Over the 24 years since the Poll Tax riot the police have been used to suppress and prevent protest to an ever greater degree. This has encouraged the belief within the police that it is they who own the streets, not us. Excessive force has not only gone unchecked – it has been endorsed by court support for ever more oppressive interpretations of the law. A closed, un-self-critical police culture leaves individual officers with little choice but to support their colleagues, even in gross breaches of the law.

© David Hoffman.

The above text was taken from a talk David Hoffman gave at the London College of Communication. As part of East London Photomonth, David’s images are on display until the end of this month at a variety of cafes forming the ‘Roman Road Cafe Crawl’. David’s show at Muxima cafe runs until 27th of November. More details here.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova.

Street singer, Brick Lane, 1982. © Marketa Luskacova. Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova

Mr. Ferenc, Obisovce, Slovakia, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1976. © Marketa Luskacova. Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sleeping Pilgrim, Levoca, 1968. © Marketa Luskacova. Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova.

Spitalfields, 1979. © Marketa Luskacova. Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova. Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova.

Tailors, Spitalfields, 1975. © Marketa Luskacova. Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova.

Bellringers, Sumiac, 1967. © Marketa Luskacova. Christmas Party at an old peoples’ lunch club in Tower Hamlets, 1975. © David Hoffman.

Christmas Party at an old peoples’ lunch club in Tower Hamlets, 1975. © David Hoffman. Street market, Cheshire Street, Tower Hamlets 1981.

Street market, Cheshire Street, Tower Hamlets 1981. Turkish baths, Clapton, Hackney 1983. © David Hoffman.

Turkish baths, Clapton, Hackney 1983. © David Hoffman. Street musician, Brick Lane, 1978. © David Hoffman.

Street musician, Brick Lane, 1978. © David Hoffman. Silver Jubilee, Tower Hamlets, 1977. © David Hoffman.

Silver Jubilee, Tower Hamlets, 1977. © David Hoffman. One Man Band, Brick Lane area, 1984. © David Hoffman.

One Man Band, Brick Lane area, 1984. © David Hoffman. Tea time at an old peoples’ club in Tower Hamlets 1975. © David Hoffman.

Tea time at an old peoples’ club in Tower Hamlets 1975. © David Hoffman.